Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

violenceLaura Palmer, wrapped in plastic

Submitted by Jenn Shapland on Thu, 2013-11-07 15:10

Image still from Twin Peaks episode two. Inspired by Casey's Halloween post on gender in the horror genre, I'm continuing to riff on the same theme; I'll talk about boredom and violence, truck stop killers, and, of course, Laura Palmer. So I just finished watching Twin Peaks. I'm behind the times in tackling this one, but now the show is up there on my list of favorites. That said, while watching over the past few months, I couldn’t help but notice that the underlying message seems to be: Young Women who display independence and/or sexual curiosity will probably be murdered by a deep woods demon. Laura Palmer is only the first casualty. By the series’ end—no serious spoilers here—we have to wonder what will become of our various other heroines. Audrey Horne, Donna Hayward, Shelly Johnson. And of course there remains the question of questions: How’s Annie? Violent Encounters

Submitted by Laura Thain on Fri, 2013-04-19 17:39

Louisville Cardinal players react to Kevin Ware's leg injury during March Madness. Image Credit: Yahoo Sports I’ll admit, I stayed up way past my bedtime last night listening to the Boston police scanner, following as closely as I could the developments in the Boston Marathon bombing. In the wee hours of this morning, I thought about documenting the dozens of news items (as well as widespread speculation across message boards and social media) to take a tally of how much of the information proliferating in the uncertainty of Friday morning would be disproved by Friday afternoon. As I began the project, it soon proved futile—there was far too much information and I ran into (as I might have anticipated) problems discerning journalistic fact from fiction right from the get go. It was only when I stopped documenting and trying to quantify the evidence that I began to think about the relationship between violence and speculative practice and assemble a quite different archive. [GORE WARNING: the images beyond this cut are NSFW and may shock and disturb some viewers. Discretion is advised.]

Part II: Suspense is Better than Action

Submitted by Chris Ortiz y P... on Sat, 2012-09-15 10:31

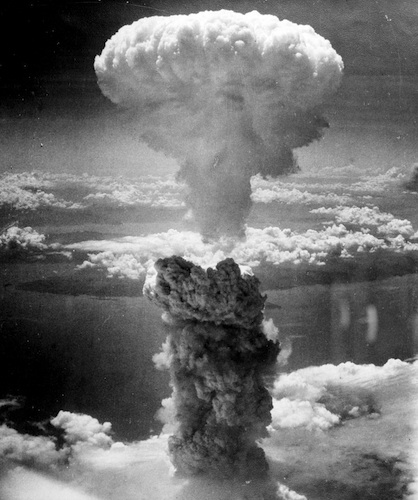

Image Credit: National Archives image (208-N-43888) Part II: An Objection is Entertained Last week I argued that suspense makes for more arresting visual effect than does what passes for “action” in Hollywood these days. My main point was that human frailty creates suspense and that psychological realism will do much to improve action cinema. Bigger visuals are not necessarily better at creating an emotional response in the viewer. Now, you may say to me: Chris, you are not taking into sufficient account how big real visual events have become.

Juarez the Video Game?

Submitted by ebfrye on Wed, 2011-02-23 11:02

Image credit: screenshot via YouTube Last week I posted a link to the much discussed Great Gatsby video game that's making the rounds. It's not like me to turn my attention to video games for two weeks in a row--no offense to anyone--but this story on NPR's "Morning Edition" caught my attention. This summer, the French gaming company Ubisoft will release a game they call Call of Juarez: The Cartel. As you might expect, the game is generating a lot of controversy due to the real-life situation of the border city. This news comes on the heels of the bloodiest weekend in recent memory, in which 53 people were killed (as reported by The Houston Chronicle). When It Can't Be Clever - Domestic Violence PSAs (part two)

Submitted by Cate Blouke on Tue, 2010-11-16 00:26

Image Credit: MTV ad via YouTube

Researching last week's viz. post about domestic violence PSAs started me down a rather depressing rabbit hole. I was curious to see how often humor was used in these ads (infrequently), but weeding through a few dozen of them yielded some interesting trends while simultaneously making me sad for the human race. This ad, narrated by Helena Bonham Carter, is a strange juxtaposition of verbal abuse acted out as physical violence. While I won't subject you to watching the plethora of PSAs that I waded through, I'll talk about trends in target audience, invisible vs. visible violence, and how these commercials may or may not have the desired effect. Beauty and the Bomb

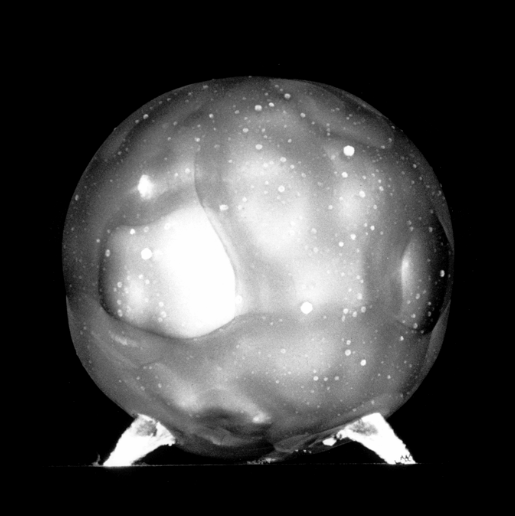

Submitted by Megan Eatman on Thu, 2010-10-07 11:43

Image: Peter Kuran, How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb, via The New York Times Inspired by Eileen's post, I focus this week on a fascinating image. If it weren't for the title of this post, or the image's caption, you might not be able to identify this image. Even with context, I spent a moment staring, attempting to understand how this could be what its caption claimed it was: the beginning stages of a nuclear blast, captured by a special camera placed two miles away from ground zero. In its deviance from the typical mushroom cloud, the image argues for an even more complex understanding of the massive destruction that humans create.

Reboot: DADT and Public Sacrifice

Submitted by Megan Eatman on Thu, 2010-09-23 12:51

Image credit: Chan Lowe, The Lowe Down The above cartoon, republished yesterday on the artist’s blog, makes a very effective argument against Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. The use of flag-draped coffins, signifying shared tragedy, suggests that dying for one’s country has little to do with sexual orientation and that is rather the work that an individual does—in this case, sacrificing his/her life for the United States—that matters. In this kind of public sacrifice, the image suggests, everything individual is erased. However, this message seems more complicated when considered in relation to one of Tim Turner's earlier posts and the wider cache of meanings that these coffins suggest. Documenting Crime, Yesterday and Today

Submitted by Megan Eatman on Fri, 2010-09-17 08:19

Image: Ángel Franco Via Lens Blog, New York Times The above image is a part of a series by photographer Ángel Franco that documents the aftermath of violence, but not in the way you might expect. The series, which is published weekly on Lens, the New York Times documentary photography blog, is filled with images that are haunting in large part because of what is not shown.

American Gothic on Mad Men

Submitted by Rachel Schneider on Mon, 2009-09-21 18:32

Image Credit: Chicago Tribune Visual Rhetoric and Violence IBy Tim Turner (Contact) What is the relationship between rhetoric and violence? Are they mutually exclusive?

The very notion of "good argument" raises questions about what is at stake in the teaching of rhetoric, however. In theory, "good argument" is argument that is persuasive. Taken in this sense, the theoretical and practical concerns of an introductory rhetoric course coincide: instructors teach students how to recognize effective, persuasive arguments written by others ("rhetoric" conceived as a theory of persuasion) and encourage students to model these techniques of effective persuasion in their own writing ("rhetoric" conceived as a practicum in writing). "Goodness" in this context is nonetheless complicated by the ethical stakes of persuasion. People are often persuaded by ethically suspect arguments: arguments that are dishonest, demagogic, or that persuade the listener to engage in morally untenable acts. (Of course, the definition of what constitutes "moral" is itself open to interpretation and, therefore, argumentation; moral critique may be subjected to rhetorical critique.) Yet there is also a connection between ethics and rhetoric in that both "disciplines" insist that one be responsive to the needs of someone else: in rhetoric, this means listening to what the other person has to say (as in the "common ground" model) and responding, sometimes by making concessions, and in ethics, for example, in considering how one's actions will impact others or those situations in which one ought to act to give assistance to others. In both cases, what is implied is a certain claim that the other person makes on me, or that I, in my turn (when I make my argument or when I act in the public sphere) make on them. Both revolve around a certain susceptibility, and this is one reason why the common ground model is attractive: it insists on notions of responsibility, or response-ability, in public, civic life. At the same time, this susceptibility potentially has what we might think of simply as a "dark side": or rather, the abstract susceptibility we have in thinking, in argument and debate, has a physical corollary in our susceptibility to bodily violence--this is susceptibility as vulnerability. In thinking about pedagogical strategies for teaching rhetoric in the past, I have tried to allow these considerations to impact the content in my courses. Most often, this means I have asked students to think about the relationship of violence to rhetoric; about texts that encourage violence; whether, as is sometimes said, violence is what happens when rhetoric fails; and even whether rhetoric itself, the forms of an argument, can be violent. To consider these questions, I have often relied on depictions of violence to conduct such arguments. In my RHE 309 course, the Rhetoric of War and Peace (a topic chosen with many of these questions in mind), these included images of violence including war films, documentaries, and photography. Including such images was not only a way to introduce some of the ethical questions at stake in the teaching of rhetoric. They also had the effect of introducing, often in uncomfortable ways, the visceral into our discussions in a non-gratuitous way. I saw such a strategy as integral to teaching rhetoric in part because persuasion itself is not always only about thought/thinking; it is usually persuasion to action.

Like many of the rhetorical strategies discussed in rhetoric classes, depictions of violence may be said (in general terms) to "move," both literally and figuratively, the audiences to which they are shown or at which they are aimed. Depictions or representations of violence may be deployed as rhetorical strategies, and this point complicates an easy sense that violence and rhetoric are mutually exclusive or that violence is only conceivable as a failure of rhetoric or in the absence of rhetoric.

Agamben's arguments are well worth consideration, but it remains an open question whether such forms of violence are ultimately reducible to purely intellectual analysis. Two issues seem to be at stake here. First, Agamben's work has the benefit of reminding us that violence is sometimes an inescapable part of the public sphere (in popular culture or in political life). He asks us to think critically and carefully about the work of violence, about its meaning and status in everyday life. In short, he asks us to think about what violence is and how it works. He asks us to see its political/civic dimension. At the same time, the potentially affective dimensions of depictions of violence challenge, in useful, productive ways, the notion that violence and rhetoric are "opposites" or mutually exclusive. While the "common ground" model of rhetorical pedagogy privileges or presumes the existence of a civil public sphere, approaches to the teaching of rhetoric that incorporate some discussion of violence offer a "rhetoric-from-the-margins" approach. Incorporating attention to violence, to the visual rhetoric of violence or to violence as visual rhetoric, asks students and instructors to think critically about the constitution of a public sphere in which, ultimately, we are asking our students to responsibly (and response-ably) participate. Questions for assessing the status of violence in the rhetoric curriculum

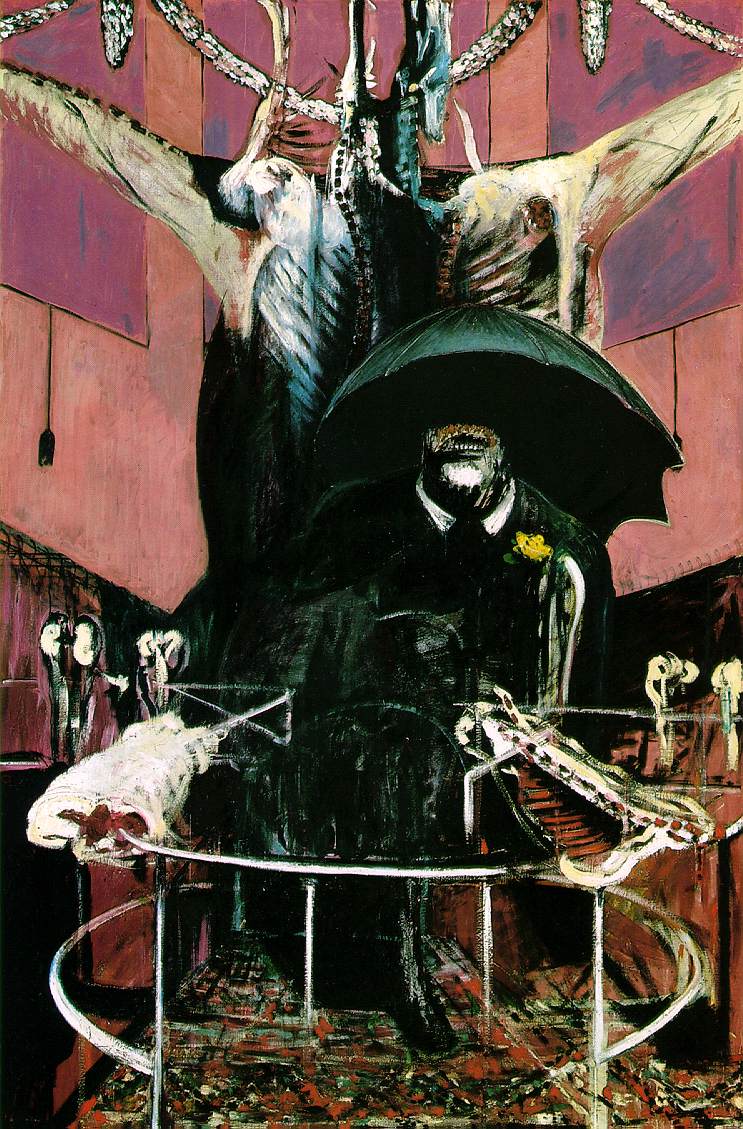

Further ReadingOn the web: In print: Image creditsUpper-right: Francis Bacon, Painting (1946; Museum of Modern Art, New York City) |

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

violence |

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have  A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes,

A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes, Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago