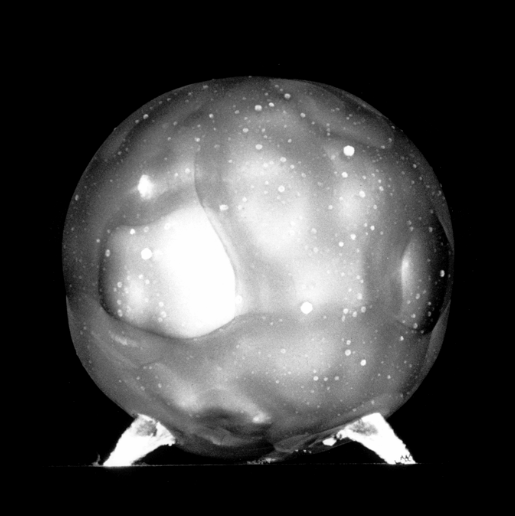

Image: Peter Kuran, How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb, via The New York Times

Inspired by Eileen's post, I focus this week on a fascinating image. If it weren't for the title of this post, or the image's caption, you might not be able to identify this image. Even with context, I spent a moment staring, attempting to understand how this could be what its caption claimed it was: the beginning stages of a nuclear blast, captured by a special camera placed two miles away from ground zero. In its deviance from the typical mushroom cloud, the image argues for an even more complex understanding of the massive destruction that humans create.

Technically speaking, this image is a close-up; it was captured with a special camera that was placed much closer than a regular camera (or a photographer) could be. But one of the provocative qualities of this image is the way it mimics a much closer close-up. Black and white, with darkness in the background, the image looks like something you might see through an electron microscope. While this aesthetic complicates perception of the actual scale of destruction, it also invokes the incredibly small action from which the massive explosion stems.

For me, the image also invokes the intersection of humanity and technology. The ball, filled with light, exudes a potentiality with no immediate point of origin; it grows on its own, as if alive.

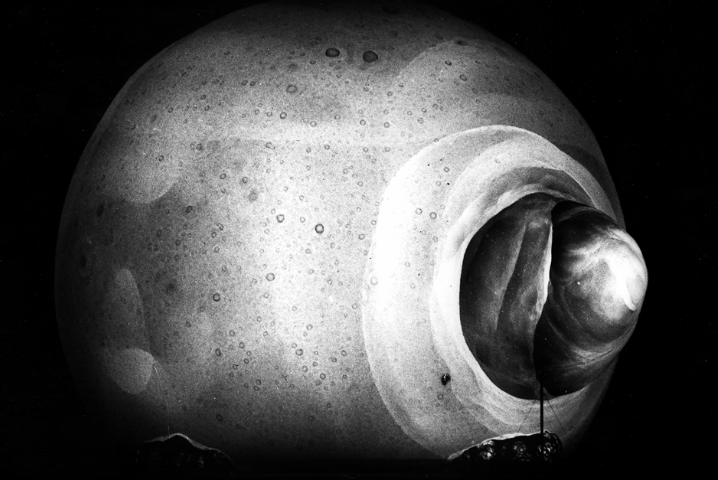

Image: Peter Kuran, How to Photograph an Atomic Bomb, via The New York Times

This image is particularly explicit in invoking growth and reproduction. The bomb looks as if it is giving birth, but to what? A caption indicates that this image shows a fireball "begin[ning] to destroy the tower that holds the weapon aloft." While the first image, taken at a later stage of the explosion, shows no indication of the weapon's beginning, this image shows the destruction of the support structure, the development of the explosion as an independent entity, and thus hints again at growth. While biological creatures are certainly not the only entities that grow independently, the birthing image seems in particular to invoke human and non-human animal reproduction, providing a stark contrast to the elimination of human life that accompanies such an explosion.

The significance of these biological visual tropes might lead us to a somewhat overtrodden message: nuclear technology destroys its maker, humans are their own worst enemy, etc. I like to think that they can do more than that. If nothing else, they force us to think about an almost unimaginable scale of destruction in a different way, considering its processes and products anew. But there is also a beauty, one that I think complicates the concerns visual scholars have long held about the aestheticization of violence. The combination of beautiful image and historical knowledge might enable the viewer to both appreciate the glories of technology and its very serious consequences.

Comments

Learning to Love (and Fear) the Bomb

Thanks (belatedly) for this great post—I’d seen the NYTimes slideshow, but hadn’t paid attention this image. I really enjoyed your points about how the photograph both plays with levels of scale and mimics organic processes. I also wonder if aesthetics might work as an entry point for non-scientists into the beauty of a scientific idea (even one, like nuclear energy, that has a kind of Terrible Beauty). Your comments here also reminded me of a post I did last year on Luke Jerram’s sculptures of H1N1 and other viruses that are deadly to humans; by subverting conventional representations, Jerram ultimately inspires a sense of awe—we can both appreciate their beautiful structures and respect their dangerous power. Provided it doesn’t come across as annoyingly self-promotional: here’s a link to that post.

Thank you for sharing your

Thank you for sharing your post on Jerram's work! I had seen plush toys of viruses before, which have a somewhat stranger message (we're intimately connected? you can snuggle them in bed?), but never these sculptures. The apparent fragility is interesting too, given the difficulty of eradicating these viruses. It seems to emphasize the specialness--something this powerful came to exist, at least in part through luck--which certainly contributes to a feeling of awe.