Site informationRecent Blog Posts

Blog Roll

|

Visual Rhetoric and Violence IBy Tim Turner (Contact) What is the relationship between rhetoric and violence? Are they mutually exclusive?

The very notion of "good argument" raises questions about what is at stake in the teaching of rhetoric, however. In theory, "good argument" is argument that is persuasive. Taken in this sense, the theoretical and practical concerns of an introductory rhetoric course coincide: instructors teach students how to recognize effective, persuasive arguments written by others ("rhetoric" conceived as a theory of persuasion) and encourage students to model these techniques of effective persuasion in their own writing ("rhetoric" conceived as a practicum in writing). "Goodness" in this context is nonetheless complicated by the ethical stakes of persuasion. People are often persuaded by ethically suspect arguments: arguments that are dishonest, demagogic, or that persuade the listener to engage in morally untenable acts. (Of course, the definition of what constitutes "moral" is itself open to interpretation and, therefore, argumentation; moral critique may be subjected to rhetorical critique.) Yet there is also a connection between ethics and rhetoric in that both "disciplines" insist that one be responsive to the needs of someone else: in rhetoric, this means listening to what the other person has to say (as in the "common ground" model) and responding, sometimes by making concessions, and in ethics, for example, in considering how one's actions will impact others or those situations in which one ought to act to give assistance to others. In both cases, what is implied is a certain claim that the other person makes on me, or that I, in my turn (when I make my argument or when I act in the public sphere) make on them. Both revolve around a certain susceptibility, and this is one reason why the common ground model is attractive: it insists on notions of responsibility, or response-ability, in public, civic life. At the same time, this susceptibility potentially has what we might think of simply as a "dark side": or rather, the abstract susceptibility we have in thinking, in argument and debate, has a physical corollary in our susceptibility to bodily violence--this is susceptibility as vulnerability. In thinking about pedagogical strategies for teaching rhetoric in the past, I have tried to allow these considerations to impact the content in my courses. Most often, this means I have asked students to think about the relationship of violence to rhetoric; about texts that encourage violence; whether, as is sometimes said, violence is what happens when rhetoric fails; and even whether rhetoric itself, the forms of an argument, can be violent. To consider these questions, I have often relied on depictions of violence to conduct such arguments. In my RHE 309 course, the Rhetoric of War and Peace (a topic chosen with many of these questions in mind), these included images of violence including war films, documentaries, and photography. Including such images was not only a way to introduce some of the ethical questions at stake in the teaching of rhetoric. They also had the effect of introducing, often in uncomfortable ways, the visceral into our discussions in a non-gratuitous way. I saw such a strategy as integral to teaching rhetoric in part because persuasion itself is not always only about thought/thinking; it is usually persuasion to action.

Like many of the rhetorical strategies discussed in rhetoric classes, depictions of violence may be said (in general terms) to "move," both literally and figuratively, the audiences to which they are shown or at which they are aimed. Depictions or representations of violence may be deployed as rhetorical strategies, and this point complicates an easy sense that violence and rhetoric are mutually exclusive or that violence is only conceivable as a failure of rhetoric or in the absence of rhetoric.

Agamben's arguments are well worth consideration, but it remains an open question whether such forms of violence are ultimately reducible to purely intellectual analysis. Two issues seem to be at stake here. First, Agamben's work has the benefit of reminding us that violence is sometimes an inescapable part of the public sphere (in popular culture or in political life). He asks us to think critically and carefully about the work of violence, about its meaning and status in everyday life. In short, he asks us to think about what violence is and how it works. He asks us to see its political/civic dimension. At the same time, the potentially affective dimensions of depictions of violence challenge, in useful, productive ways, the notion that violence and rhetoric are "opposites" or mutually exclusive. While the "common ground" model of rhetorical pedagogy privileges or presumes the existence of a civil public sphere, approaches to the teaching of rhetoric that incorporate some discussion of violence offer a "rhetoric-from-the-margins" approach. Incorporating attention to violence, to the visual rhetoric of violence or to violence as visual rhetoric, asks students and instructors to think critically about the constitution of a public sphere in which, ultimately, we are asking our students to responsibly (and response-ably) participate. Questions for assessing the status of violence in the rhetoric curriculum

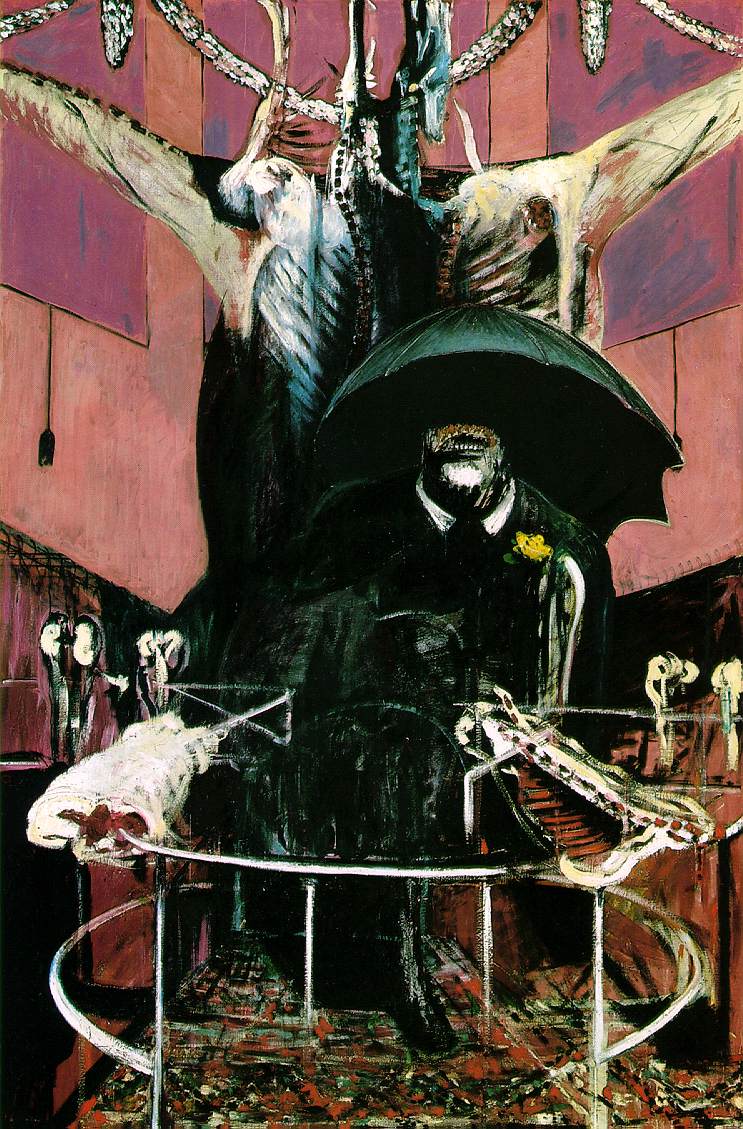

Further ReadingOn the web: In print: Image creditsUpper-right: Francis Bacon, Painting (1946; Museum of Modern Art, New York City) |

viz.

Visual Rhetoric - Visual Culture - Pedagogy

Site informationRecent Blog Posts

|

Visual Rhetoric and Violence I |

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have

These questions may pose challenges to the prevailing pedagogical models employed in introductory rhetoric classes, which tend to be organized around the "common ground" model of civic or "civil" discourse. As I have  A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes,

A survey of some of my fellow instructors indicates that while violent images and imagery often form part of the 309 curriculum, the role played by depictions of violence in pedagogical strategy may remain undertheorized. However, the prevalance of such imagery (which may simply be related to the overall prevalence of violence in forms of popular culture) in 309 courses indicates that instructors recognize the pedagogical uses to which violent imagery may be put. One instructor writes, for example, that "Students actually seem drawn to the most violent imagery; it illicits a real response from them. I think that when they see violent imagery they feel compelled to respond." This notion is echoed in the response of another instructor, who writes, Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Finally, the status of violence in rhetoric classes is further complicated by the potential disruptions of meaning it may impose. More straightforwardly, this analysis begs an important question: what is violence? This may well be a question for definitional argument: how do we, or even how can we, think about, discuss, represent, or understand violence? Recently, for example, this question has especially been an issue in discussions of the Holocaust (as I have discussed in

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago