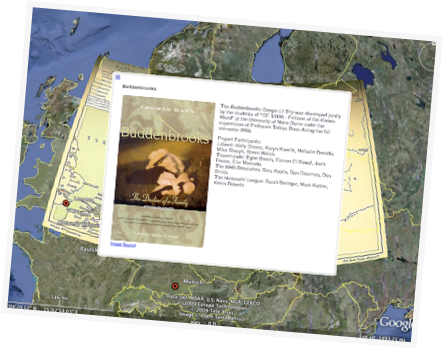

(Image Credit: Google LitTrips)

As I’ve been previewing Google Earth educational

applications on the web, I’ve noticed that while many disciplines (science,

geography, history) are using Google Earth to engage students and invite them to

create within the software, applications for the English classroom (at least

those that are featured and discussed on the web) overwhelmingly take the form

of teacher-made presentations. I

imagine that this tendency speaks to an ongoing conservatism about the design

of writing assignments, a desire to retain the five-page paper as the product

of the literature and writing classroom.

In a video presentation that I’ll discuss later in this

post, Sean McCarthy, a graduate student at the University of Texas, admits that

there may, in fact, be an “amateurism” that attends writing in the Google Maps

environment, but suggests that perhaps there are some benefits to this amateurism. This quality, he suggests, may open up a

level of analytical adventuresomeness that the more formal structure of the

essay quashes.

I’m interested in

this suggestion, but before I explore it further, I want to address some more

common uses of Google Maps and Google Earth technologies in the literature and

writing classroom. I’ve noticed

that the use of these technologies takes three main forms: Mapping as a

Presentation Tool, Mapping as an Analytical Tool, and Mapping as a Writing

Tool. Of course, these uses

overlap, but the discrete categories generally reflect the way the software is

actually being used in the classroom.

Mapping as a

Presentation Tool

As I mentioned above, presentations are overwhelmingly the

primary, much-evidenced use of Google Maps and Earth technologies in the

literature classroom. The Google

for Educators site

offers a collection of Google LitTrips

as their recommended idea for using Google Earth in the English classroom. The LitTrips include maps of The Narrative of the Captivity and

Restoration of Mary Rowlandson, James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks.

In the latter case, the LitTrip was created by German literature students

at Notre Dame, but this student-created example is the exception.

The Google Earth Education Community,

run by David Herring, a long-time teacher at University High School in Tucson,

Arizona, similarly focuses on presentations, providing instructions for

teachers to build presentations and a space for users to share their Google

Earth presentations. The Google

Earth presentations on Herring’s site include “The Life and Works of Jane

Austen,” “Locations in Shakespeare’s Plays,” as well as maps for William Least

Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways and River Horse, and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. While these presentations offer useful

geospatial conceptualizations of literary works, they do not take advantage of

the technology’s capacities for encouraging students to think and write in new

and networked mediums.

Mapping as an Analytical Tool

In the aforementioned video presentation on Google Map

pedagogies,

University of Texas graduate student Sean McCarthy explains uses of Google Maps

that extend far beyond getting directions. McCarthy shows how students can use the maps' built-in analytical

tools such as the terrain map, satellite map, and street view, as well as the

optional “overlays,” including articles from Wikipedia, photos from Panoramio,

and video from YouTube to analyze geographical and social spaces and their

online construction.

He suggests that students might be divided into groups to

examine a city, its neighborhoods, its layout, its public transportation and other services, its parks and greenspace, and its history using such user-generated

data.

He also notes that such an examination requires students to examine

the rhetorical construction of Google Maps itself. Which areas show street views? Which areas include large amounts of user-generated content,

such as links to Wikipedia articles and YouTube clips?

Mapping as a Writing

Tool

While the above example engages students directly with maps,

it stops just short of asking students to actually create compositions in

dialogue with these technologies.

McCarthy has a number of suggestions for how to get students

writing in Google Maps. Here are

just a few:

- McCarthy features an assignment designed by University of Texas graduate student Amena

Moinfar, in which students map the national origin of each player on the French

soccer team, Les Bleus, to help

them conceptualize the reach of French colonialism and the ongoing effects of

the French-Algerian War.

- McCarthy features a student-created map of the

history of rugby that shows the sport’s presence overwhelmingly in the southern

hemisphere. The student who

created this map discovered through this process the connection between rugby

and colonialism.

- McCarthy suggests asking students to create a map

alongside a formal, five-page paper, as the map allows for reflection and for a

different mode of presenting research and representating connections.

- McCarthy features a student map, created in real time

during the uprisings in Tibet and elsewhere in protest of the Beijing

Olympics. McCarthy notes that

because the student created the map in the networked space of Google Maps,

linked it to his blog, and kept updating it, the map turned into a real public commentary on the protests, which in fact got thousands of

hits.

As is evident in the last assignment described above,

composing in Google Maps places students’ writing into a socially networked

environment. McCarthy joins many composition scholars, including

Sharon Crowley and Michael Stancliff, when he argues that placing students’

writing into contexts that extend beyond the classroom enriches the

compositional activity and connects students to audiences, which raises the stakes of the writing activity. He

further argues that creating and sharing content is, indeed, the way students

are increasingly accustomed to writing: according to McCarthy, 60% of all

19-year-olds publish on the web every day through social media outlets such as Facebook.

While composition and literature instructors may prefer the familiar, formal, linear structure of the traditional essay, McCarthy's findings suggest that the "amatuerish" writing student sometimes produce when composing in digital mediums in fact bespeaks the quality and complexity of their research and analytical connections.

There are more Google Maps- and Google Earth-related

assignments indexed in the DWRL’s database of technology-based lesson plans. If you plug “Google Maps” into the

site’s search bar, you’ll easily turn them up.

Comments

DWRL Geo-Everything Project Group

The new DWRL Geo-Everything Project Group has been at work all year on researching and developing a variety of pedagogical applications for Google Maps and Google Earth.

Project Leaders Caroline Wigginton and Jeremy Dean recently led a Google Earth Workshop that introduced some of the Group's research thus far and included an overview on using Google Spreadsheet Mapper, which allows users to brand placemark templates and enter data for personalized maps and tours in Google Earth and Google Maps. An agenda and handouts with step-by-step instructions are available at the Workshop link above; tutorials are also available at Google Earth Outreach. A video of the workshop will soon be available through the DWRL Communications Project.

Project leaders and members Catherine Coleman and Shelley Manis have been generating an archive of Google Earth and Google Maps lesson plans that is available, as Laura points out, through DWRL's Pedagogy Lesson Plans.

Google Earth finds new hominid!

Check out the role that Google Earth played in the discovery of a new hominid specicies in South Africa:

"Dr. Berger said the path to the discovery began over the Christmas holidays in 2007 when he began using Google Earth to map caves in the Cradle of Humankind. On a recent visit to his office, he rotated Google Earth images of the dun landscape on his desktop, showing how he spotted the shadows and distortions of the earth that gave clues to the location of caves, often topped with wild olive and white stinkwood trees."

NY Times, 8 April