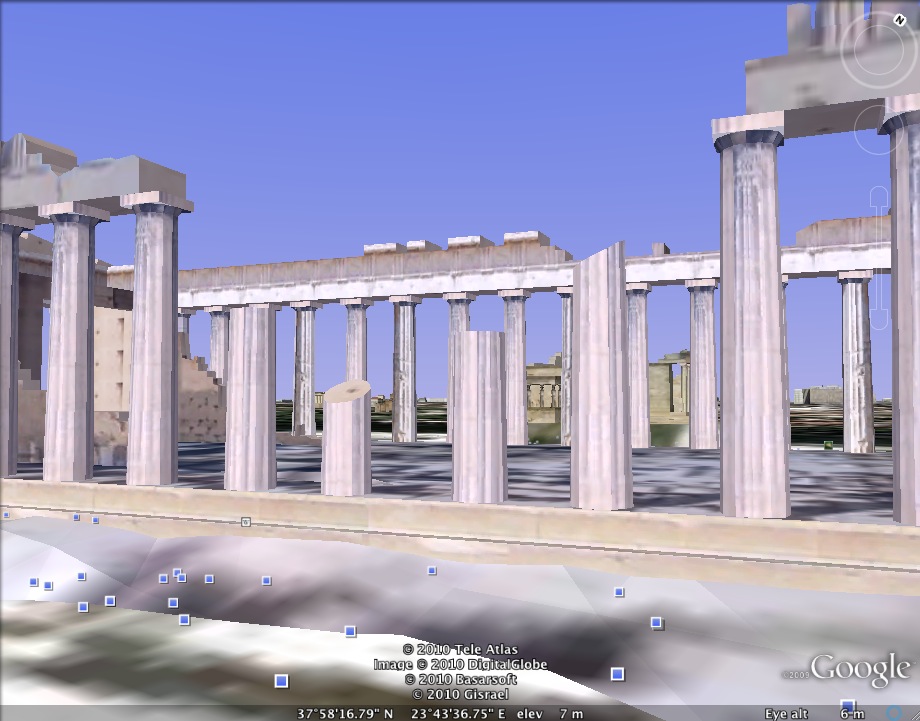

(Image credit: Image capture of the Parthenon in Athens, Greece from Google Earth)

A fellow graduate student recently mentioned to me that his

rhetoric professor had used Google Maps to show classical Athens to the class. He told me, “I kept thinking how much

cooler it would have been if we were looking at it in Google Earth, walking

around down there in street view.”

It’s true. As

shown above, a street view of the Acropolis is, indeed, pretty cool. There is a simple and undeniable “wow”

factor about flying to and viewing sites in Google Earth. But it’s been my contention throughout

these blogs that the use of the Google Earth technology can go beyond the

“that’s so cool” factor and can actually enhance and expand composition

pedagogies. Former DWRLer Jim

Brown (now of Wayne State University) makes this point, too, as he discusses

possible evaluation strategies for Google Maps assignments. Brown writes, “These maps are writing.

They are not just some ‘cool’ thing that will then require a ‘real’ writing

assignment. This assignment should open up important discussions about how

cartography is a form of writing and about how ‘the map is not the

territory.’ Students are creating

something here, not merely reflecting an existing reality” (Brown, “Mapping

Home”).

Brown’s assignment, like most of the assignments I’ve found

so far, asks students to work in Google Maps, not Google Earth. But the writing component is

applicable. The activity he designed, called

“Mapping Home,” asks students

to map key sites in their daily lives, using the map to elucidate the “borders”

that they negotiate or cross regularly.

The link above includes a sample map created by Brown. Using the “My Maps” function in Google

Maps, each of Brown’s students created a individual map with an introduction

and placemarks with text and embedded links, images, or video.

To get the most out of the assignment and to aid evaluation,

Brown encourages instructors to set their expectations about students’ maps:

- How many placemarks should students create?

- What components should placemarks include?

- How much text should placemarks include?

- What components, if any, besides placemarks,

should maps include? (Should they include border lines, connecting lines, or

other vectors, for example?)

- Should the map include an introduction? What should the introduction

accomplish?

- Is an accompanying reflective essay required, or

should the map itself (or an in-class discussion) accomplish the task of

reflection?

Other assignments using Google Maps technology include

Jeremy Dean’s “Map Three Readings,” which asks students to use a map to “draw a physical and thematic

connection” between multiple readings by placing authors or characters on a

map, and Eileen McGinnis’ “Mapping Galapagos,” which asks students to map landmarks and events in Kurt Vonnegut’s

novel, Galapagos. McGinnis frames the map as a thinking process, not a product, at least at the outset: “Keep

in mind that your map will function initially as a tool for discovering

something unexpected about the novel rather than for charting the Known World.”

These assignments demonstrate well how writing within maps

can aid students’ invention process, prompt students to make visual, spatial,

and physical connections within and across texts, and can, themselves,

constitute an argument (thereby denaturalizing mapping as an authorless or

objective rendering of space).

Most of these assignments were created before the release of

Google Earth, however, so they might be adjusted or reformulated to more fully

take advantage of Google Earth’s distinct capacities, such as its capacity to

show non-static data, to depict historical change, to show beautifully-rendered,

3D buildings, to travel from site to site via a user-generated animated tour, to offer

various annotation options via clickable layers, and to move quickly between

macro and micro views of the same landscape. While some

of these features are available in Google Maps, Google Earth’s animation

feature allows users to dramatize these functions, heightening their effect.

Google Earth’s homepage includes a Gallery of selected tours and animations that demonstrate the

technology’s advanced functions.

These animations give a sense of the informational and analytical uses

of features particular to Google Earth, such as 3D buildings, historical

timelines, and the ability to travel. The Gallery includes tours of major world cathedrals, castles, libraries, and universities, as well as an animation of major international flight routes. Each file must be opened within Google Earth, so users must download the software, which is free and available on the same site, to view the demonstrations. It's also important to note that users must find in Google Earth's left-hand sidebar an icon that looks like a movie camera. Clicking this icon will "run" the file.

As I mentioned two weeks ago, the DWRL’s Geo-Everything

Group has been putting together resources to familiarize instructors with

Google Earth and help them integrate it into the writing classroom. Their recent Google Earth Workshop

provided a practical introduction for using Google Earth in the classroom,

including tips for making basic and customized placemarks and using Google’s

data template, Spreadsheet Mapper, for creating collaborative maps with

“branded,” standardized placemarks.

I recommend taking a look at their Google Earth Workshop handout for practical guidance to getting started in Google Earth.

Comments

Geo-Everything Rocks!

As a RHE student, I'm fascinated by the Geo-Everything Project.

I was lucky enough to sit in on the Google Earth workshop. Watching a timelapse of the Palace and cathedral in Haiti gave a powerful experience of the destruction caused by the quake.

We also created a tour of New York led by Jay Z!

I recommend everyone check out the Google Earth Workshop. There's clear instructions on how to create tours and explore the digital world.