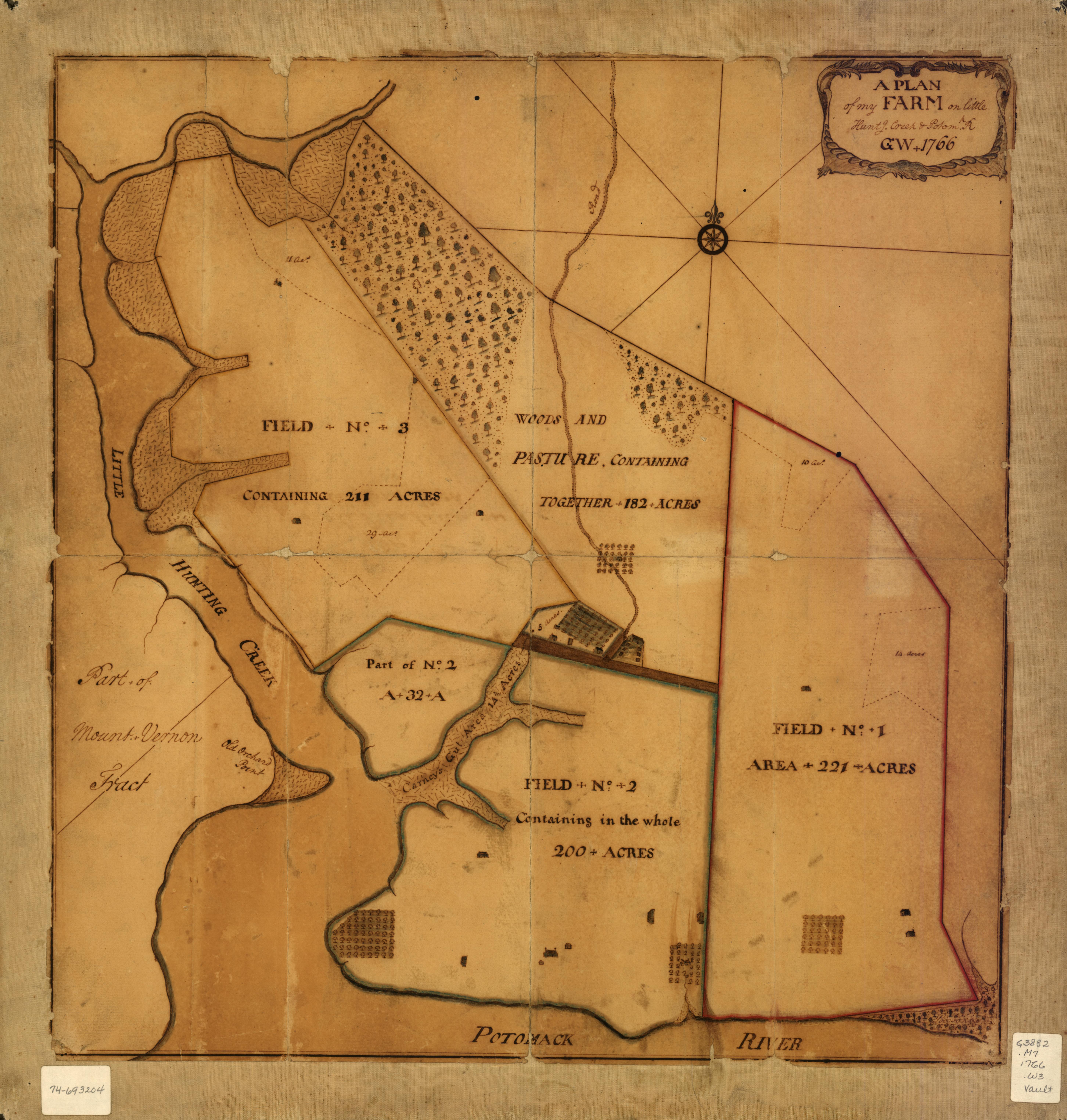

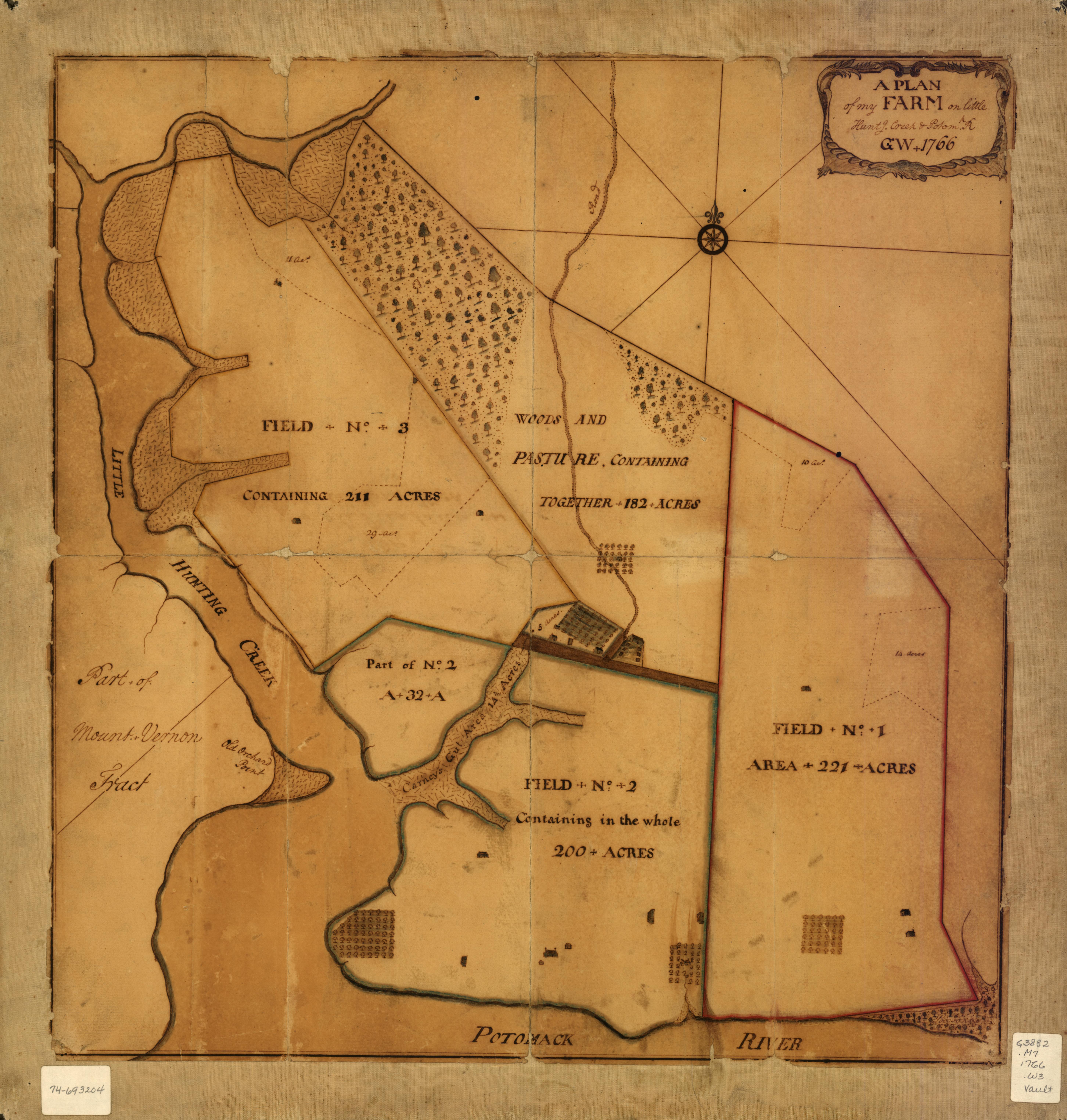

(Image source: Library of Congress Map Collections)

The above map, created by George Washington in 1766, depicts

“A plan of my farm on Little Huntg. Creek & Potomk.” This map, which is publicly viewable at the Library of Congress Map

Collections and downloadable as a high-resolution JPEG2000 file, is included

in the Collections’ “Cultural Landscapes” section, which highlights the ongoing

cultural construction of United States and World landscapes through the ways individuals, communities, and nations modify land. This subsection of the online

Collection places an array of cartographic materials into conversation: a set

of local maps authored by George Washington, a series of maps of Liberia

created by the American Colonization Society, and a store of historical U.S.

atlases.

One of the distinguishing features of The Library of

Congress’s Map Collection is that it is part database, part exhibit. The online Collection boasts

sophisticated cataloguing and imaging standards, allowing users to zoom in on

maps, examine details, download high-resolution image files, and refer to

helpful notes about the map’s physical features and provenance, including

scale, media, size, accompanying materials, and source. The site also offers helpful advice

about copyright, noting that materials in the collection are generally not

copyrighted materials; the maps “were either published prior to 1922, produced

by the United States government, or both.” The site clearly aims to make the Library’s

cartographic collections freely available and digitally accessible and to

encourage users to download and use these materials for study, education,

research, and enjoyment. The site

intersects at many points with the Library’s larger “American Memory” project,

which has digitized over five million items from the Library’s Collections since

1996.

I am interested in the possibilities of a maps database such

as the Library of Congress Map Collections partly because of the prospect of

using historical maps within Google Earth, and partly because our Visual

Rhetoric workgroup is preparing to host an upcoming workshop, “Best Practices

for Digital Images”

on Friday March 26th at 1 pm.

One component of the workshop will be an introduction to the many rich

image databases that are available on the web. To that end, some of our posts over the next few weeks will

serve to review and evaluate some of these databases.

Three significant, online map

databases are The Library of Congress Map Collections,

the Perry-Castanada Map Collection

at the University of Texas Libraries, and the David Rumsey Map Collection.

These collections all have large holdings that are available

to the public and offer downloadable images, though only the Library of

Congress and the David Rumsey Collection offer consistently high-resolution

downloads. (The Perry-Castanada

Map Collection seems to prioritize keeping files to a manageable size for its users; the website claims that most of its images, usually JPEGS or PDFs, are kept to size standards of 200K to 300K.) These three collections, run by a

federal organization, a public university, and a private company, respectively,

vary widely in terms of cataloguing and indexing practices, image quality, image

context, and general online experience.

My aim today will be to offer a very brief overview of the

first two image collections, Library of Congress Map Collections and the

Perry-Castanada Map Collection. (I'll discuss the Rumsey Collection in a later post.) I

will give an expanded analysis of the features and utility of Library of

Congress’s Collection for pedagogical applications.

The Library of Congress Map Collections, the online arm of

the Library of Congress’s Geography and Map Division, represents a small

fraction of the holdings of the Map Division’s collection, which includes more

than 4.5 million items. The

Library of Congress Map Collections began as a massive digitizing project in

1995. The Library does not estimate how many maps are online, but

notes that new materials are digitized and added continually.

The Perry-Castanada Map Collection includes more than

250,000 maps, 11,000 of which are available for online viewing. (In addition, maps from the

Perry-Castanada Map Collection can also be physically checked out by students,

faculty, or the general public for a two-week borrowing period.) As I noted above, the Perry-Castanada

Collection does not prioritize providing high-resolution images or downloads of

their materials; their files, generally formatted as JPEGs, GIFs, or PDFs,

are considerably smaller than those of the other two sites. The Perry-Castanada Collection does

offer categorized links to hundreds of other map collections though, including

the Library of Congress and The Rumsey Collection, as well as other research

collections and independent web sites.

While each digitized map is indexed in the Library’s general catalogue, the

Maps Collection does not include the catalogue information or a link to the catalogue entries, so, in fact,

the amount of information about the map available with the image is minimal, usually including the title

of the map or atlas in which it was printed, its publication date, and sometimes the organization that

published or produced it. The

user has to separately look up the map in the online catalogue to

obtain full information. The full catalogue entries offer additional information such as the map’s

author, but the general purpose catalogue does not give the depth of information

one might expect from a special collections catalogue entry, including detailed notes about medium, size,

inscriptions, accompany materials, or provenance.

As I noted earlier, the Library of Congress Map Collection

works like a database and an online exhibit at once. The materials are indexed via a number of different methods: the

whole collections is divided into seven major thematic categories, which allow

users topical entry into the cartographic resources. Those categories include

- “Cities and Towns” (which includes a number of

panoramic maps, a cartographic style popular in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries)

- “Conservation and Environment” (including the

subcollection, “Mapping the National Parks”)

- “Discovery and Exploration”

- “Cultural Landscapes”

- “Military Battles and Campaigns” (including

American Revolution and Civil War maps)

- “Transportation and Communication” (including a

collection of Railroad Maps)

- “General Maps”

Nearly every collection includes a “Special Presentation,”

an online exhibition with text and images that invites users to delve into some

selected resources within the collection, rather than using the site

by entering specific search terms.

This feature allows users to have a curated, museum experience, clearly

serving not only the Library’s goal of making documents available to the

public, but also its educational goals.

While users can browse within these thematic categories, which

include their own Collection Guides, users can also search by keyword, or

browse indexes by geographic location, subject, map creator, or map title.

Indeed, as the above list of browse-able indexes suggests,

the site relies heavily on browsing to make its resources available to users.

For example, as the visitor enters the Railroad Maps Collection,

she finds only a very cursory introduction to the collection—a total of five

lines of text—on its home page, and this Collection happens to include no

curated “Special Presentation” to introduce the user to the Collection’s

material, so searching or browsing become her best methods of accessing

information. Fortunately, the

Geographic Location Index offers a robust, visual, clickable map icons to help users locate materials by

country (Canada, United States, Mexico, and West Indies), U.S. region, and U.S.

state.

In this way, the Library of Congress Map Collections site

combines sophisticated cataloguing methods with an inviting, browse-able online

environment. The icons that

accompany the seven thematic categories perhaps best express this mission of the site: each is a

collage of multiple materials from the category, with numbers identifying the source of each element of the collage, which are clickable:

(Image source: Library of Congress Map Collections)

The Cultural Landscapes icon, for example, pairs a detail

from the 1766 Washington map (pictured in full at top) with a detail from an 1867 American

Colonization Society map, “St. Pauls River, Liberia at its mouth.” The clickable collage, which links to

each element's catalogue page, represents the site’s values: user-based discovery (facilitated by either browsing or searching), curated experience, thematic intersections, accessibility, and high-quality image and cataloguing standards. By clicking on the category icon, the user not only enters the "Cultural Landscapes" section, but is confronted by provocatively juxtaposed visuals accompanied by links to each detailed source page.

Not surprisingly, the site offers extensive materials for

teachers, including classroom ideas, lesson plans, and primary source sets

(groups of images related to a historical period or theme) through its

“Collection Connections” section.

The Collection’s choice of somewhat unusual file formats for

images is, perhaps, an unfortunate extension of the value placed, at once, on

accessibility and high quality that I appreciate throughout most of the site. Rather than offering more common image

file formats such as TIFFs GIFS, or JPEGS, the Library has chosen to compress

their large documents as JPEG2000 and MrSID files to preserve detail and enable

high-resolution downloads. Both of

these formats require plug-ins, and while the site offers links to free

versions, I would have liked to have available a low-resolution option (a GIF

or JPEG) that required no software plug-in.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago