Image Source: Gorgonetta

As gifs begin to occupy more and more space in internet discourse, I’ve been contemplating the various ways they reinvent older media forms. New media theory tells us this is an inevitable historical trajectory; it is not just a characteristic of post-broadcast media but embedded in mediation as an ideological concept. What I find particularly interesting about gifs is not just how they remediate the television shows, films, Youtube videos, and memes from which they derive meaning, but also how they relate to a much older form of media: silent film. And in such a reading, the overlap between the production of fame and celebrity in the silent film tradition and in current gif discourse is remarkable—and worth discussing.

In order to describe such a relationship, we might first turn to scholarship on the production of celebrity in the realm of silent film. A problem we must account for in exploring this topic is that, while mass-produced and marketed motion pictures begin at the turn of the 20th century, no form of cinema stardom existed in mass media until at least 1910, if not later. One common historical narrative argues that celebrity resulted from the battle between actors/actresses and film production companies. Although audiences wanted to know the names of performers, production companies resisted billing their actors and actresses in order to maximize their profit margins. It was not until the breakup of Edison’s Patents Trust by anti-trust legislation and the victory of independent film studios that the “star system” emerged as the direct result of specific shifts in production.

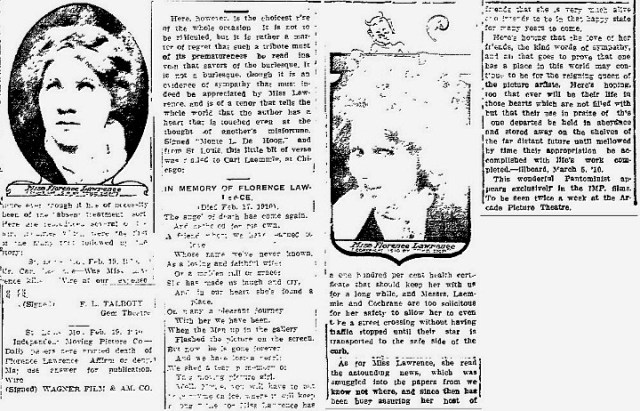

Clippings of Florence Lawrence, Biograph Picture's first leading lady, "obituaries" after her death was faked as a pubicity stunt by her agent, Carl Laemmle. Note the anonymous poem referring to her as the actress "whose name we've never known"--before her fake death, Lawrence was known only as "Biograph Girl." Image Source: 11e14thstreet

Richard DeCordova’s Picture Personalities: The Emergence of the Star System in America (Illinois, 2001) provides a productive counter-narrative. De Cordova argues that celebrity cannot be accounted for by examining shifts in production alone—we must understand its development as a discursive category. “The star system,” he argues compellingly, “is not simply the creation of one person or even one company; nor is the desire for movie stars something that arose unsolicited [among audiences].”

Instead of focusing solely on the development of film production, DeCordova describes a larger phenomenon: the emergence of a “discourse on acting.” A precondition of this discourse was the separation of the actor from the film itself. As the public began to understand moving pictures as a remediation of theatre, conceptions of the actor in the filmic space developed to account for the role of the actor and the actor him or herself. A difference between on-screen and off-screen presence was established. The result of such a distinction is what DeCordova calls a “picture personality.” Audiences traced these “personalities” across films, producing a discursive space in which actors and actresses were recognized intertextually and the role of an actor in one film was associated with the character he played in others. (In this sense, all actors and actresses of early film became recognizable to the public as “character” actors and brought with them from film to film assumptions about the dramatic space they inhabited. Mary Pickford was the ingénue, Douglas Fairbanks the swashbuckling hero, Charlie Chaplin the tramp, etc.) Still, picture personalities were associated with the films in which they appeared, not their private lives.

Mary Pickford in a 1920 publicity still. Image Source: Library of Congress

DeCordova concludes by arguing that the term “star” (a true film celebrity) can only be applied when an actor’s personal life is available for public consumption. The personal (“off-screen”) life of the actor becomes the new center of truth and authenticity. Only then can we consider actors in films true “celebrities.”

What does any of this have to do with gifs as a medium? Like early film, gif fame depends on intertextuality. The discursive space occupied by the gif strongly resembles the discursive space DeCordova gives to the “picture personality.” Gif fame is not located in an interest in the personal lives of the characters it adopts, but rather in the proliferation and reproduction of images that continue to reinvent meaning. Like silent film, gifs have an embedded “meme” function. If we read memes as “an element of a culture or system of behavior that may be considered to be passed from one individual to another by nongenetic means, especially imitation” (OED) we can see the meme in silent film—how it communicates cultural concepts through characterized gesture and intertextual association, through the actor, in some sense, “miming” him or herself. The gif accomplishes this function by reproducing the same gesture to respond to different contexts. In this way, gifs divorce themselves from the realm of celebrity created after the “picture personalities” of early silent film, even as they rely on that celebrity to creative enough traction to hedge out their own ideological space. One need not, for instance, be familiar with the TV show or film from which a gif is extracted if one is familiar with other intertextual applications of the gif as an ideological concept (its embedded function as “meme”). For example:

Audiences need not watch The Real Housewives of Atlanta to interpret the signature gesture of Nene Leakes here.

Image Sources: RealityTVGifs

This Harry Potter-inspired gif can be coupled with a variety of captions--it captures an emotion, rather than a specific narrative.

Image Source: WhatShouldWeCallMe

This happens in terms of both a gifs adherence to and defiance of its own “meme” function. In part 2 of this post, I’ll explore the “meme” function of both silent film and gif culture, drawing parallels between the two in order to further demonstrate how gifs reinvent old media not only in terms of discursive space, but in the formal characteristics of the medium itself.

For Part 2 of this post, click here.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago