Scientific American has published a short guide listing five methods that researchers use to spot altered or retouched photographs.

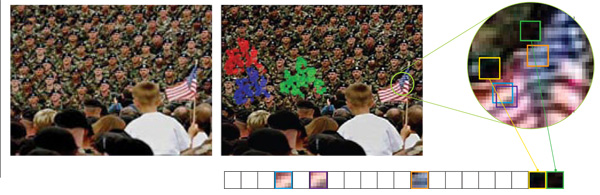

For example, in the image above, some of the soldiers in the background have been “cloned” to make it appear that the crowd was more dense than it actually was.

While the guide details the mostly algorithmic methods used by Hany Farid and his fellow researchers, it also has some practical tips which can be used to identify altered photographs with the naked eye.

To infer the light-source direction, you must know the local orientation of the surface. At most places on an object in an image, it is difficult to determine the orientation. The one exception is along a surface contour, where the orientation is perpendicular to the contour (red arrows right). By measuring the brightness and orientation along several points on a contour, our algorithm estimates the light-source direction.

For the image above, the light-source direction for the police does not match that for the ducks (arrows). We would have to analyze other items to be sure it was the ducks that were added.

Related:

Digital forensics

Photo-retouching guru

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago