Image Credit: BookDrum.com

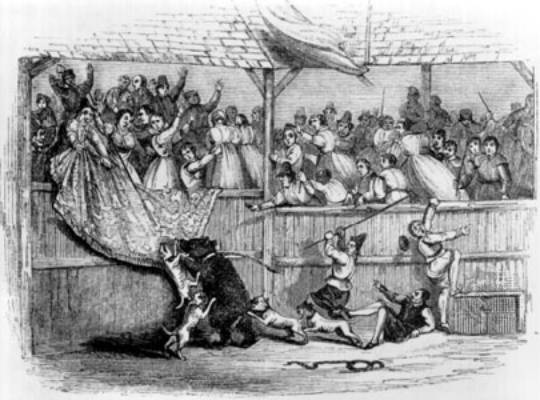

I suspect I was one of very few people thinking of the First Earl of Shaftesbury, Anthony Cooper, as I watched The Hunger Games with my family last weekend. In particular, I was recalling how Shaftesbury lamented in 1711 that the English theater had come to resemble the “popular circus or bear-garden.”

It is no wonder we hear such applause resounded on the victories of Almanzor, when the same parties had possibly no later than the day before bestowed their applause as freely on the victorious butcher, the hero of another stage, where amid various frays, bestial and human blood, promiscuous wounds and slaughter, [both sexes] are… pleased spectators, and sometimes not spectators only, but actors in the gladiatorian parts.[1]

I found myself watching The Hunger Games at the urgent behest of my eldest daughter, a staunch tween member of “Team Peeta.” Before the movie, we had made a bargain that I would read the entire Hunger Games series and take her to the film if she would read Golding’s Lord of the Flies. It seemed like a good deal at the time. While The Hunger Games movie didn’t put her in mind of Shaftesbury, she did direct me to the image below:

Like the best jokes, this one works on several levels. Suzanne Collins, author of the

Hunger Games series, makes the Roman “bread and circuses” connection explicit in the third novel when Katniss is informed that “in the Capitol, all they’ve known is

Panem et Circenses.”

[2] Indeed, “Panem” is the name of the fictional nation that uses the annual Hunger Games as a strategy of control. My initial assessment after reading the series was that Shirley Jackson’s famous 1948 short story “The Lottery” had mated with Stephen King’s prescient 1982 sci-fi novel

The Running Man and

produced dubious offspring. But I left the movie musing that it is somehow too easy to assess

The Hunger Games as a commentary on a culture obsessed with cheap, voyeuristic reality TV. In a way the books never could, the movie takes advantage of the social and visual experience of going to the movies to breathe new life into the “bread and circuses” paradigm.

In an article for Huffington Post, Greg Garrett noted that The Hunger Game’s dystopia evokes both 1930’s Depression-era America and the Roman “bread and circuses” tradition. Garrett writes, “So long as we are distracted… we may forget for a moment about our own lives, our own hunger. We may forget that we live in a nation that is less free than it was a decade ago, a nation with fewer societal safety nets, a nation with fewer opportunities for young people.”[3] Well said. But let’s face it; the majority of Americans have never known anything more than metaphorical hunger. Turning our gaze toward our own very real problems is a start, but only a start. To do only that is to become a Panem Capitol dweller who realizes she lacks freedom. Breaking free of the thralldom imposed by our own enticing bread and circuses requires we turn our gaze outward and recognize responsibilities extending beyond the borders of self, town, state, or nation.

The theater where my family viewed The Hunger Games was a trendy one that serves meals during the show. While we waited for our group to be seated, the people in front of us consumed two pitchers of the theater’s own microbrew. Once inside, we were treated to a menu mimicking foods found in the books. No, not squirrel, berries, or any other survival food found in the impoverished districts or the arena. This was high-end Capitol fare, like lamb stew with plumbs and some purple melon wrapped in prosciutto. In typical American fashion, the portions were huge. All told, my family probably spent over $100.00 to sit in stadium seats watching a decadent society watch starving children kill each other for sport.

That purple prosciutto melon was a tip off to what sets The Hunger Games phenomenon apart. It casts the movie audience in the role of Panem Capitol dwellers watching the games. The effect is emphasized by how rarely the movie shows Capitol citizens reacting to the action in the arena. Instead, we stand in for that audience, watching the carnage directly or through the mediation of the charismatic game show host, Caesar. The outlandish Capitol fashion (think Eighteenth-century meets Lady Gaga) may be meant to distance these people from us, even dehumanize them, but as the movie rolls on we become them.

Shaftesbury recognized that the difference between being a “spectator” or an “actor” is perhaps only one of degree. The Hunger Games has us watch colonial children kill one another while we participate in our own consumer culture of excess. God forbid you were out refilling your eight-dollar popcorn tub and missed Thresh bashing little Clove’s head in against a giant metal cornucopia.

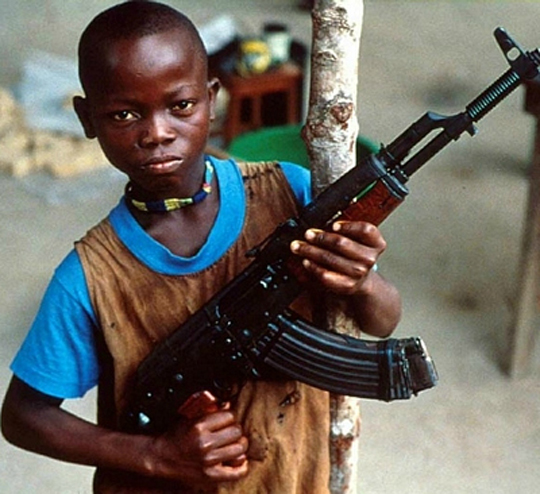

Image Credit: Netroots Foundation

The tricky thing about a movie about bread and circuses is that it can become simply another circus, particularly if the audience remains unaware of their complicity. What are we forgetting – what are we being distracted from – by this particular circus and by the more ubiquitous barrage of media white noise? I couldn’t help but reflect that only about a week prior to the release of The Hunger Games the viral social media campaign “Kony2012” had filled our feeds and prompted anxious articles in The Atlantic,[4] The New York Times,[5] ForiegnPolicy.com,[6] and in other mainstream media outlets. The rapidity with which critiques of Kony2012 surfaced revealed a deep mistrust for new social-media fueled activism, as well hinting at even less savory reasons for lashing out at the video.

For a moment, Kony2012 brought our attention to the plight of child soldiers, real starving children who kill one another. Of particular impact is the moment nine minutes into the film, where the filmmaker attempts to explain Joseph Kony to his own five-year old son. The moment has power precisely because, in order to expose the exploitation of children, the filmmaker exploits his own son. It is uncomfortable, but it is meant to be. When we watch fictional children fight in the Hunger Games arena, however, we are partaking in an entertaining diversion, both within the framework of the fiction that makes us a Capitol citizen, and in our role as real consumers of media. A little more discomfort might be in order.

Shaftesbury wasn’t arguing for the abolishment of the theater in 1711, no more than I am denying the value of entertainment. I study Renaissance and Eighteenth-century literature for most of my day, so for me to take such a stance would be absurd. But I do think we should reflect upon what it means to be identified not with the rebellious underdogs of District 11, but with the effete, privileged citizens of the Capitol who move from one distraction to the next as children kill each other and the temperature rises.

Works Cited

Comments

The viewer's complicity

I really enjoyed your post, Dave, and am glad you were able to turn the Alamo Drafthouse's prosciutto-covered melon into such delicious blog-fodder. I do see your point (and Shaftesbury's): the act of viewing implies some complicity. (Even if you don't approve of Snooki, by watching her you still contribute to a televisoin market driven by Snookis.)

I wonder, though, how you'd read the news footage of the Vietnam War along these lines? People tend to explain resistance to the Vietnam War as coming in part from footage of the dead Vietnam soliders. Is this an example of how, say, Rue's sad death invited rebellion on the part of the outlying Panem districts against the Capital? Or does this demonstrate that action only is possible through an identification with the viewed subject? Is Kony 2012 an example of our failed sympathy?

Complicity

Rachel,

Thanks for the response. War footage is a great example of an attempt to create a similar dynamic of complicity, whether to argue against the war or as propaganda for it. Compare the war footage of Vietnam to the "embedded" reporters of the Iraq War. It also might be worth thinking about how control over war reportage has developed since WWII to the present day. And, of course, in a democracy all citizens are complicit in their nation's wars.

I would hesitate to call Kony2012 an example of "failed sympathy." The situation may be such, but the viral campaign itself was stunningly successful, as evidenced by our having this conversation. A month ago, very few people knew who Kony was. Despite the campaign's imperfections, it certainly achieved its aim of making Joseph Kony infamous.

What I'm trying to highlight is the possibility of a dystopic vision such as The Hunger Games of forcing audiences to recreate the attitude of the oppressor if they acquiesce to that subjectivity unthinkingly. And outside the frame of the fiction, how do we relate that experience to real-world horrors such as described in the Kony video? How uncomfortable should we be as we watch (and root for) these children killing other children? Between the microbrew and the goat-cheese tart, should we reflect on how many real, starving children died?

The books operate differently, by the way, which is one reason I thought this discussion belonged here at .viz. The reader lives more in Katniss's head and therefore experiences the horror of the games from her somewhate naive perspective. I expect the movie audience's perspective will shift in the sequels as the focus shifts to rebellion, but since Katniss remains quite oblivious to her role for so long it is open to interpretation.

By the way, I feel obligated to admit that it wasn't the amazing Alamo Drafthouse that served the purple melon prosciutto thing. It was Flix Brewhouse.

Fancy Foods and "Failed" Sympathies

I actually saw the movie at the Alamo and I thought they had melon because I remembered the lamb stew; but no, the Alamo is serving Peeta's strawberry cake and Prue's goat cheese. Too many fancy places to watch movies in Austin!

You have a good point about "failed sympathy"--I was thinking "failed" in the sense of encouraging specific action, but I suppose that wouldn't be failed sympathy in a Smithian sense, as people did feel and react to Kony 2012 and the Capitol citizens did react to Katniss/Peeta. (And should I feel bad as a fellow member of Team Peeta that I see the same as their oppressors and want them to kiss for my amusement?)