Image Credit: Google Streetview Gallery

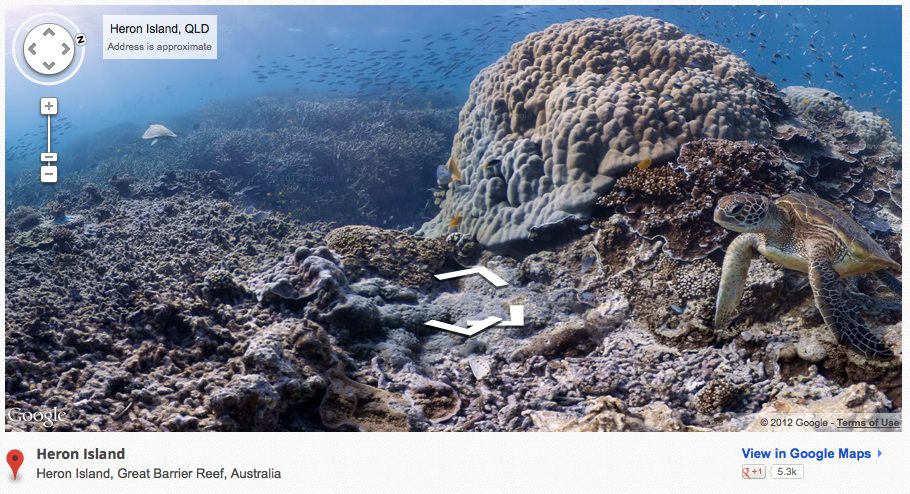

Google Maps has a remarkable new feature called Sea View that spotlights oceanic life and space. Sea View is essentially the marine version of Street View, a layer of Google Maps that allows users to navigate though 360-degree panoramic images of the Earth's surface. By extending the concept of Street View to the ocean floor, Google has added six coral reefs to the long list of cities, landmarks and parks users can currently explore remotely, from the comfort of their digital devices. The fascinating images captured so far by Google and its partner, Catlin Seaview Survey, bear out the imaginative quality of the overarching project. It's almost as if Sea View is Google's attempt to fulfill a common childhood fantasy: to experience what it would be like to live under the sea. With its zoomable and virtually traversable underwater imagery, Sea View enables adults and children alike to realize this wish (without having to worry about oxygen supply or the expense of travelling to distant coral reefs).

The look and purpose of these new images disinguish them markedly from the aerial and street views that we normally interact with in Google Maps. Catlin's director told CNN that the goal of the Sea View project is to generate interest in underwater ecosystems and spur the general public to preserve them. The public may have initially used the traditional Street View in a similar vein--out of a sense of curiosity or wonder. But since its debut, Street View's main purpose has shifted to utility; people use the tool because it helps them to recognize the destination they are trying to reach. How pictures of an underwater seascape could ever offer this kind of utility to the ordinary person is difficult to figure.

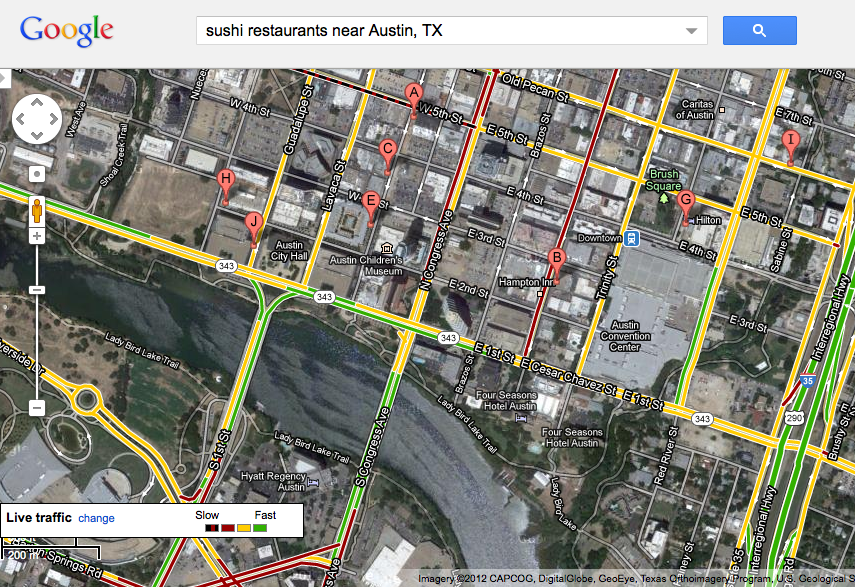

Image Credit: Google Maps

Thus the juxtaposition of the two environments--terra firma and the ocean floor--within the same, searchable platform (Google Maps) is both striking and a bit puzzling. The screenshot above, showing a bird's-eye view of downtown Austin with its traffic patterns highlighted and sushi restaurants pinpointed, contains a map that is deliberately designed to organize and communicate information. Every pixel is laden with navigational data which may ultimately be converted into cash via ads and sales. The networked surface of the place--stamped with symbols, labels and outlines of the city's infrastructure--looks nothing like the surface of the sea just off of Heron Island, a cay east of the Australian coast. The vista (below) overlooks the water surrounding the island, which is now penetrable to the online world thanks to Sea View. When compared with Google's land maps, the unmarked appearance of this stretch of blue suggests one or both of the following: that something about the ocean actually resists tidy quantification, or, that (at least so far) Google has nobly refused to parcel it up.

Image Credit: Google Maps

Much of the available underwater imagery supports the first conclusion, that marine worlds do not readily lend themselves to virtual mapping and, in general, are difficult to gain one's "footing" in. Take for instance the murky water (below) surrounding Lady Elliot Island, another reef-fringed habitat east of the Australian mainland. The navigational arrows at the center of the viewfinder denote a pathway through the haze, but they do not give the user a sense of where she is going, or even which cardinal direction she is facing. The lurching action that occurs between frames further displaces her in the fog. She feels a bit like Satan tumbling through Milton's Chaos, an "Illimitable ocean without bound, / Without dimension, where length, breadth, and height, / and time and place are lost" (PL II. 892-94).

Image Credit: Google Streetview Gallery

Perhaps this is the point of the technology. It seems ironic, but Google might actually be encouraging us to get "lost at sea" through the unlikely medium of a mapping program. As it turns out, the underlying idea that Internet maps and browsers can facilitate tidal drift is not as new or outlandish as one would think. Recall, for instance, the mother of all Internet browsers, Netscape Navigator, whose trademark icon was the helm of a ship. The Netscape wheel was an apt synecdoche for a vessel-like piece of software that allowed users to rove freely around the web. (It was also a tribute to the company's founder, Jim Clark, whose obsession with computerizing a giant sail boat is wittily documented in The New New Thing by Michael Lewis.) Thus, it's possible that Google's dive beneath the waves is part of a bid to take us back to the good old days of internet surfing, which were arguably less about fixing our location--tagging and marking the virtual space around us--and more about exploration and immersion: floating weightlessly like a sea turtle through a vast expanse of images and texts.

Image Credit: Google Streetview Gallery

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago