Image Credit: Screenshot from Tiny Subversions

When you live in Texas, you get used to people asking you to verify certain popular stereotypes: cowboy boots, country music, ten-gallon hats, and conservative politics. And—a belief in the capital punishment. The facts are bleak: Texas leads the nation in executions, with 510 since the death penalty was reinstated in Gregg v. Georgia in 1976. To compare, the next closest state, Virginia, has only executed 110 people. While the number of death penalty sentences have declined since 1999, organizations like The StandDown Texas Project and The Texas Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty have advocated to either suspend or completely end the death penalty in the state. Numerous problems have been cited, from the shortage of drugs for lethal injections to protests about foreign nationals not being given their proper consular rights. While such logos-based arguments commonly circulate, another kind of ethos-based argument works through various art projects which seek to remind viewers of the humanity of the convicted.

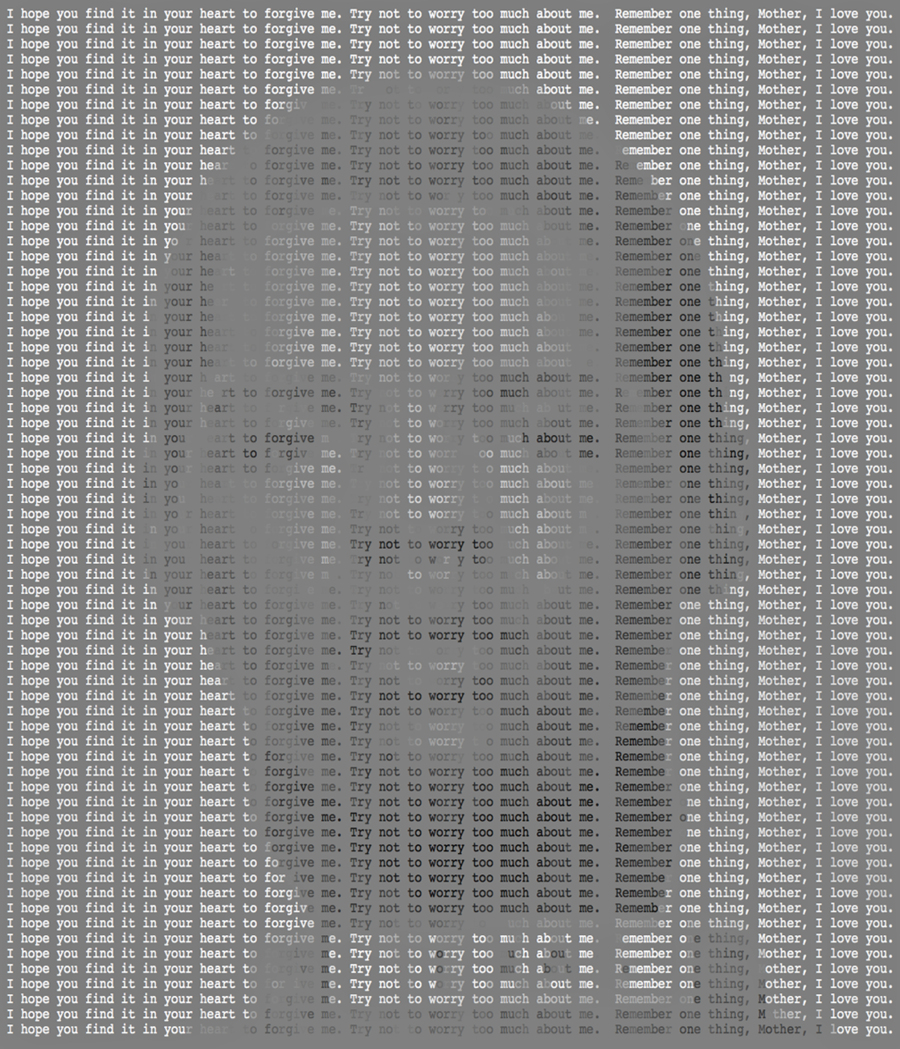

Image Credit: Amy Elkins

H/T: Huffington Post

These online art projects work to reconstruct the ethos of these violent offenders. For example, Amy Elkins’s series Parting Words uses the final statements of the executed to construct their mug shots. For an example, see Elliot Johnson’s. The face is relatively obscured, but the grayscale type conveying the message—“I hope you find it in your heart to forgive me. Try not to worry too much about me. Remember one thing, Mother, I love you.”—becomes the man’s face. These tender words serve as a stark contrast to the dehumanized headshot, providing a new view of the violent criminal.

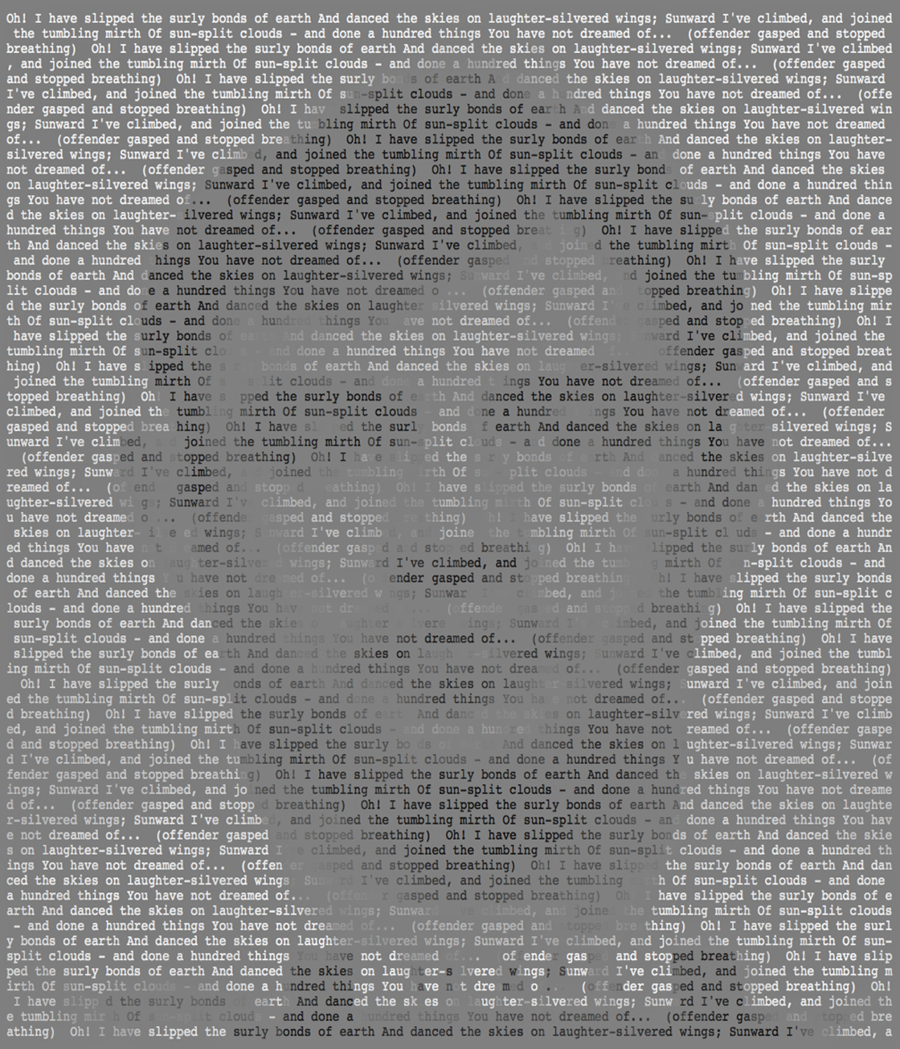

Image Credit: Huffington Post

Another man, Robert Black Junior, quotes from John Gillespie Magee’s poem “High Flight,” but his recitation trails off at the suggestive lines “— and done a hundred things / You have not dreamed of.” A poem written about flight during World War II becomes a man’s death-cry, an autobiographical narrative. Matched with the illegible portrait, the effect is eerie.

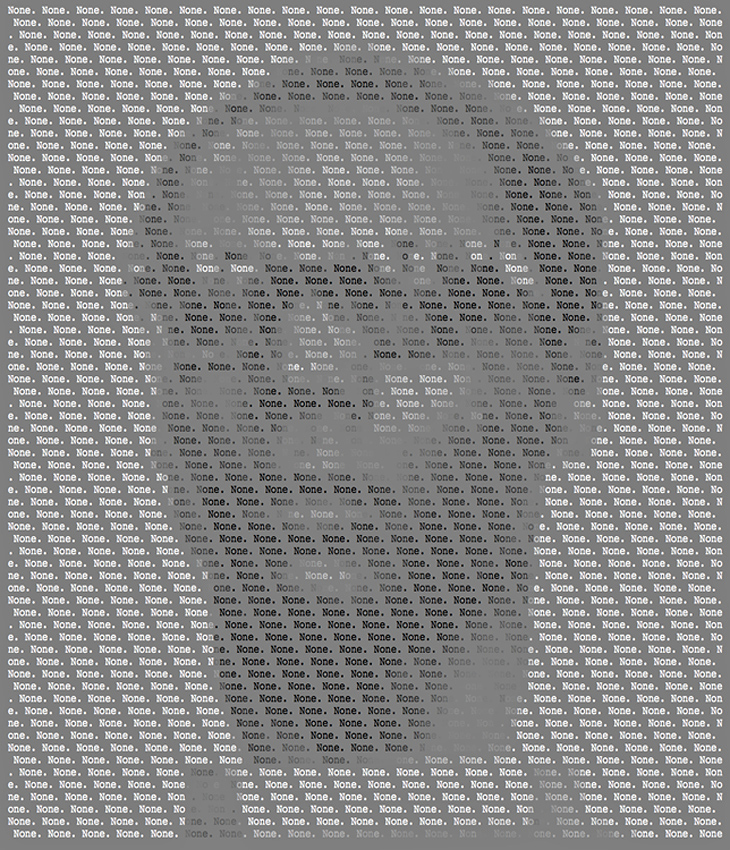

Image Credit: Amy Elkins

Samuel Hawkins’s portrait manages to touch the viewer through a different strategy. The absence of a final statement—here represented as “None”—reminders its audience of how depersonalized the industrial prison complex is. That there is probably more than Hawkins said in life, or could have said in the moment is put into relief by the fact that nothing was said here.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Tiny Subversions

Last Words, an art project by programmer Darius Kazemi, flashes lines from these last statements which include the word “love” in them, presented in white sans serif typeface against a black background. While Elkins’s portraits are in part powerful because they highlight the individuality of each inmate, these try to communicate the shared humanity between the prisoners and their audience through this shared emotion. The bleakness of the screen underlines the point also that these are last words, that while these people killed others, their lives are now over, available for mourning as well. If you sit and watch the page for several minutes, you’re likely to see certain repetitions: different spellings of “I love y’all,” gratitude for love and support, empathy with the victims’ families. Because these statements are all online, the viewer can choose to try and find out who said what, but the work relies on removing the statements from their specific individual context.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Tiny Subversions

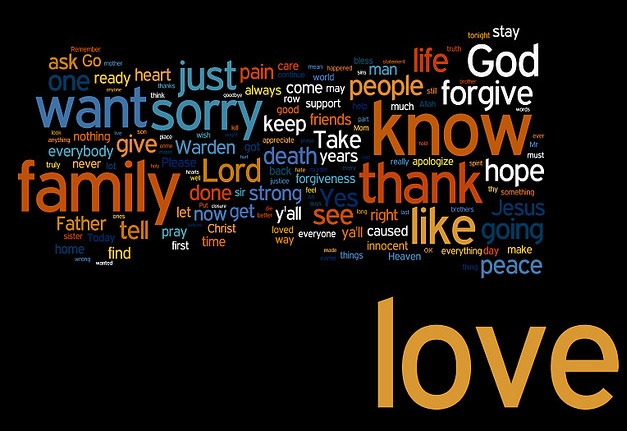

The gradual appearance and disappearance of the text as shown here runs similar to a movie credit sequence, giving you a minute to consider an individual sentence before it gradually fades, to be replaced by another. The effect is somewhat mournful, and gives a completely different context and feeling to the language than something like this Wordle, which highlights in a different way how prominent the word “love” is in these final statements.

What strikes me as interesting about these different pieces is that all rely on the visual impact of the physical word to perform their plea for empathy or understanding. While the final statement is clearly an important rhetorical act for these individuals, the presentation and recontextualization of their words in visual forms turns these moments into an implicit critique of a dehumanizing process, even if only rarely do the inmates themselves protest the processes entrapping them.

Comments

ethos vs pathos

I love how you resisted some of the more obvious pathos appeals and unpacked visual ethos in this archive. Nice work, Rachel.