Hacked Leviathan Frontispiece. Image Credit: David A. Harper

Hacked Leviathan Frontispiece. Image Credit: David A. Harper

In the coffee shop where I ‘m writing, there are two large bulletin boards in a high-traffic area (the hallway leading to the restrooms). We all know how bulletin boards and advertising work: once a provocative image draws you in, the text informs you, proselytizes you, or sells something to you. On a well-used board layers upon layers of images vie for attention, each individual post contributing to an unintentional artistic whole. Gathered on the same bulletin board, even the most antagonistic images are put into dialog as the physical wooden frame becomes a conceptual one. We find patterns in the noise. These old-fashioned bulletin boards have been on my mind this week while I explored the high-tech virtual pinboards of Pinterest.

Our predisposition to find order when confronted with a variety of images reminds me of Thomas Hobbes’s use of the “perspective glass” metaphor in Leviathan. These quaint seventeenth-century devices made one coherent (and often surprising) image out of a variety of disparate ones. In Leviathan, Hobbes claims that “passion and self-love” act as perspective glasses in reverse, making every obligation imposed by the state seem a multitude of divergent grievances, whereas “moral and civil science” act as a perspective glass properly reducing a multitude of potential miseries into one less-obnoxious obligation to the state (XVIII.20). Similar to well-constructed perspective glass images, Pinterest invites us to make meaning from a variety of images organized by users of the social media site. Displaying a variety of images, a Pinterest user invites an audience to decipher a composite image of self. However, while the perspective glass contained a lens carefully calibrated to reveal the underlying composite image, Pinterest leaves that task to the viewer.

Image Credit: www.toutfait.com

Image Credit: www.toutfait.com

Pinterest is the latest social media addition to an ever-more layered palimpsest of media revising older forms of authorship. Email transformed the epistolary art. The personal webpage gave individuals a bully-pulpit. Facebook and its competitors created a hybrid of webpage, text-messaging, and email to allow people to engage in an ever-evolving conversation or exhibitionist performance. Now, Pinterest has created an online commonplace or scrap book. Pinterest users fill virtual corkboards with images from the web (or from other user’s boards), using it like a visual Twitter account. It is a new, visually-centered performance space that encourages self-representation primarily through images.

Image Credit: David A. Harper via Pinterest

Image Credit: David A. Harper via Pinterest

In 2008, E.J. Westlake noted that performances of self on Facebook are “energetic engagements with the panoptic gaze: as people offer themselves up to surveillance, they establish and reinforce social norms, but always resist being fixed as rigid, unchanging subjects.”[1] Self-representation on Pinterest is both more public and more abstract than the text-based performances of Facebook. It is more public because Pinterest doesn’t allow the same level of audience customization as other social media. Every Pinterest user can view, comment upon, and repin every post. It is more abstract because it is visual. A simple browser plug-in allows users to easily pin any image they find on the web to boards they create and title with names like “Wants,” “Yummies,” or “Books I’ve Read.” Pinboards are categorized by choosing from tags such as “Art,” “Film, Music and Books,” “Cars and Motorcycles,” and “Geek.” A user’s collection of virtual pinboards comes to represent them to the Pinterest community. However, since captions are limited to 500 characters, it is the images rather than text which must bear the interpretive weight.

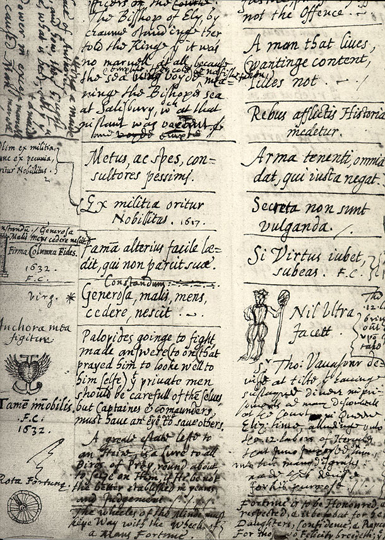

Like the coffee-shop bulletin board, Pinterest boards create narratives through the juxtaposition of images. However, unlike the unintentional artistry of accretions on a public bulletin board, personal Pinterest boards (not to be confused with those run by bots) are organized by the pinner to perform for the panoptic gaze. Neither linear nor constantly in motion like the Facebook timeline and newsfeed, Pinterest encourages viewers to construct meaning by considering the entirety of a user’s board or boards. And since the majority of the images were not created by the user, the site functions like an early-modern commonplace book into which readers copied out choice quotes from books they had read.

Image Credit: University of British Columbia Press

Image Credit: University of British Columbia Press

Just as the quotes in a commonplace book are not creations of the compiler, most images on Pinterest originate from a source outher than the pinner. It is thus not the artistry of the images themselves, but the skillful choice and categorization of them that tell the pinner’s narrative, performing self-representation through appropriation. A recent Mashable Infographic reports that 80% of Pinterest images are repins from other users, compared to Twitter where only 1.4% of tweets are retweets. Even the 20% of pins that aren’t repins are far more likely to be captured from web pages than to be original creations. The site is designed to encourage this appropriation. When a user repins an image, they not only fit it into their own categorization scheme, but they may enter their own description, replacing previous interpretations of the image with their own.

This mechanism of appropriation by repinning makes Pinterest a formidable advertising tool. Each new pin creates another link pointing back to the original source, increasing potential click-through traffic and the source’s visibility to search-engine algorithms. A quick look at some statistics suggests other reasons marketers love it:

- Pinterest ranks among the top 30 U.S. sites by total page views.

- Pinterest users are predominately female, ages 25-44, and well educated.

- The fastest growing categories on Pinterest are “Food,” and “Style and Fashion.”

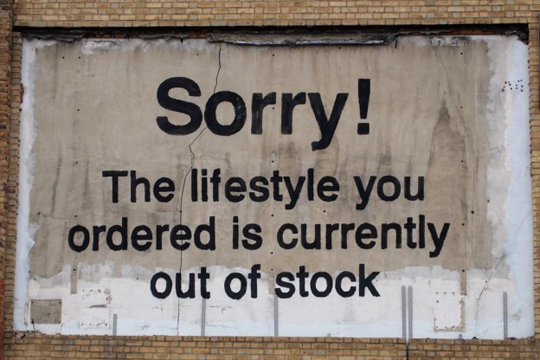

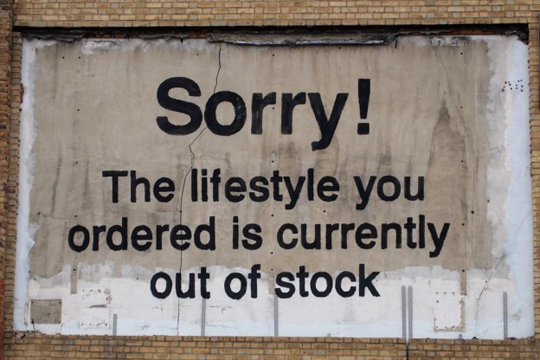

Image Credit: Bansky

Image Credit: Bansky

Pinners aren’t only creating representations of self, but they are also sometimes unwittingly tailoring online catalogs driving traffic to ecommerce sites. An ecommerce company that sells home furnishings told CNBC that customers directed to their site from Pinterest spend 70% more than those from other social media. The Pinterest consumer has seen the product contextualized within another pinner’s self-representation (as a “want,” a “need,” a “lifestyle,” or perhaps as “art”) and already has a developed desire for the product. By giving product images contexts that integrate them into idealized frames, Pinterest users do the marketers’ work for them more effectively than a store catalog could.

Recently, Pinterest has been in the news because they joined with other social media to discourage content encouraging anorexia or other forms of self-harm. The move was sparked by the alarming number of “thinspiration” posts on the site. But because Pinterest encourages wide-scale appropriation, once an image is pinned it takes on a life of its own. Whatever contextualization was granted the image by its original caption and categorization may be obliterated or reversed by the first repin. Images that were pinned as part of an “anti-thinspiration” board may be re-categorized by the next pinner as “thinspiration” itself. Context may be everything, but on Pinterest it is transient at best, as the images themselves quickly become orphaned texts uprooted from any single, fixed context.

Image Credit: GrandForksHerald.com

Image Credit: GrandForksHerald.com

In Leviathan, Hobbes defined “wit” as the ability to observe similitude and combine disparate things, while “judgment” was the ability to differentiate (VIII.3). Pinterest provides a rich field where we can exercise these faculties, both while gathering images and whether we are viewing a friend’s board or Barack Obama’s. Ultimately, meaning becomes a collaboration between the gatherer and the viewer; however, as the viewer becomes the gatherer, images that once formed part of our composite self-image drift across the landscape of Pinterest and the web, providing someone else raw material to use as they fashion their own self.

Works Cited

[1] Westlake, E.J. "Friend Me If You Facebook: Generation Y and Performative Surveillance." Drama Review. 52.4 (2008), 23.

Hacked Leviathan Frontispiece. Image Credit: David A. Harper

Hacked Leviathan Frontispiece. Image Credit: David A. Harper Image Credit:

Image Credit:  Image Credit: David A. Harper via

Image Credit: David A. Harper via  Image Credit:

Image Credit:  Image Credit:

Image Credit:  Image Credit:

Image Credit:

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago