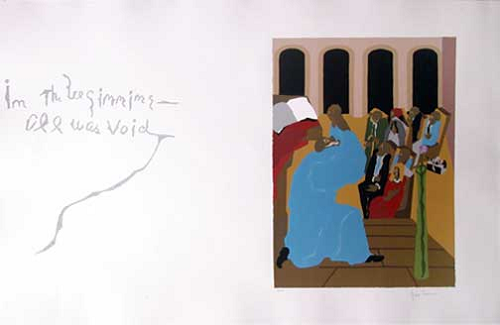

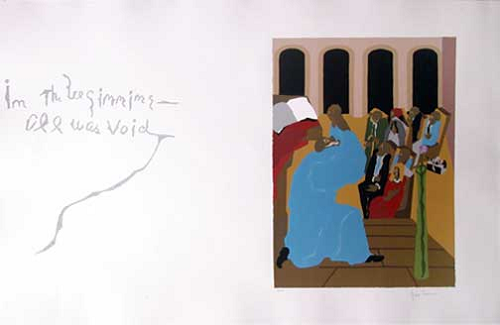

Lawrence, no. 1: ("In the Beginning--All was Void") Image From: Bill Hdoges Gallery

Replete with bright flashes of color, the "Genesis" series of Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000), currently on display on the back wall of the Harry Ransom Center's King James Bible exhibition, pulled me in like a tractor beam from across the room. It is perhaps only appropriate, then, that the subject of this series is an enthralling spectacle of storytelling and creation.Though Lawrence is perhaps best known for his "Migration Series," a sixty-panel retelling of the African-Americans' migration across the United States, Lawrence's comparatively short (8 panel) portrayal of the narration of Genesis deserves attention for its ability to express a powerful sense of motion in a single place.

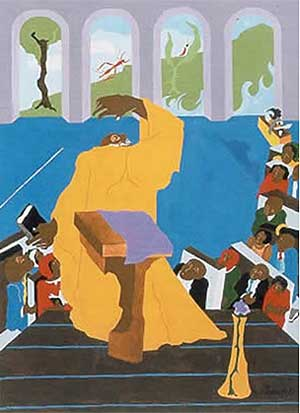

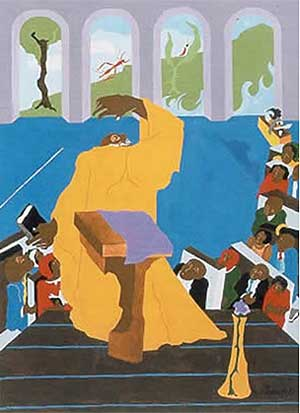

Lawrence, no. 2 "(And God Created Day and the Night and God put Stars in the Sky")

Image from: Savannah College of Art and Design

As the Savannah College of Art and Design tells us, Lawrence based his paintings on his memory of Reverend Adam Clayton Powell Sr.'s sermons at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, New York. Throughout the sequence, we can see that while the setting remains the same, the preacher's sermon literally transports the parishoners around the room, and, seemingly through space as well. The world outside appears to totally change, filling in from the "Void" pictured above and yielding to a rich world of plenty.

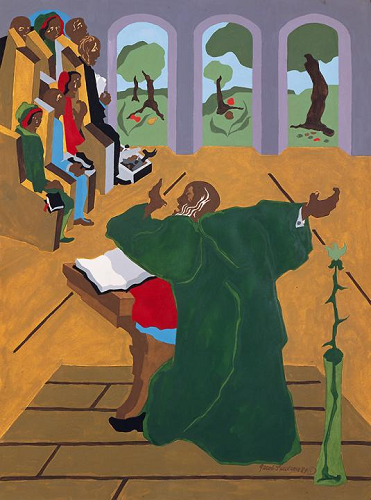

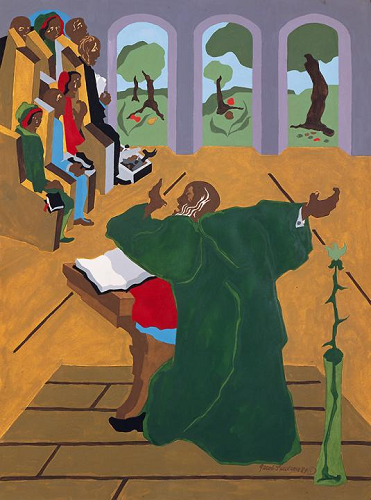

Lawrence, no. 4 ("And God Said -- let the Earth bring Forth Grass, Trees, Fruits and Herbs") Image from: Savannah College of Art and Design

As we move through the images, we can see how the preacher's expressive motions remain at the front and center of the image, capturing a sense of direct inspiration from above and radiating from the text itself. The shifting colors of his cloak, the flower vase near him, and the room itself capture a feeling of constant transformation as well. We also notice gradual changes in the arrangement of the congregation. Enthralled by the story being told, we see the congregation shifting their seats, sometimes staring at the preacher, sometimes looking up to the heavens, and on other occassions looking out the window. The neighborhoods of Harlem were in fact a major influence for Lawrence's artistic motiffs and color schemes, and their arrays of clothing, frequently synchs up with the varieties of colors inside the church and outside the windows.

Lawrence, no. 5: ("And God created all the fowl of the air and the fishes of the sea") Image from: Savannah College of Art and Design

Lawrence, no. 5: ("And God created all the fowl of the air and the fishes of the sea") Image from: Savannah College of Art and Design

Another significant image that we can trace throughout the images is a small box filled with tools.

Lawrence: nos. 6 ("And God Created all the Beasts of the Earth") and 7 ("And God Created Man and Woman") Images from Savannah College of Art and Design

As the images progress, we see the box behind and next to the pews (visible at the very top in image 6 and at the rear of the pew in image 7). But in the final image (below), which places the entirety of the congregation near the window showing a completed creation, the box sits in front of the group of parishoners.

Lawrence, no. 8. ("The Creation was done--and all was good") Image from Savannah College of Art and Design

This shift, I suggest points to the passing of the torch from God to the people. With his work completed, it's time for people do their own work as they look at the feast of plentitutde and creation before them. In doing so, Lawrence demonstrates a legacy between the holy text, its mediator, with the community's sense of common purpose.

Lawrence, no. 5: ("And God created all the fowl of the air and the fishes of the sea") Image from:

Lawrence, no. 5: ("And God created all the fowl of the air and the fishes of the sea") Image from:

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago