Image Credit: Brandeis.edu

"Books are Weapons in the War of Ideas" portrays the book as a concrete opposition against the Nazi campaign to suppress free expression. This poster represents the base of a literary monument hardening into brick, creating a wall against the forces of anti-intellectualism and hatred. On one level, the text and image disagree as to whether books constitute a weapon or a barrier. On another, the vulcanized page promotes the binary of "us" versus "them," which is required to motivate citizens to armed resistance. The essentialism of this binary, unfortunately, needs to be called into question. Courses in modernist poetry prove that not all fascists were anti-literary, just as twentieth-century American history (or even the recent nightly news) shows that "we" also take our turn at book-burning. Far from denying the clear differences between Axis and Allies during World War II, we might consider how the poster's instrumental definition of books gestures toward a paradoxical complicity subtending the opposed acts of creation and destruction. Such an inquiry inverts the more conventional topic of how certain forms of preservation might actually threaten the existence of art and literature. Speculation into the creative capacity of book-burning has surprisingly rich antecedents in Alexander Pope's eighteenth-century poem, The Dunciad, and in Jorge Luis Borges's reflections on that poem in his mid-twentieth century essay, entitled "The Wall and the Books."

http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/exhibitions/2011/banned/

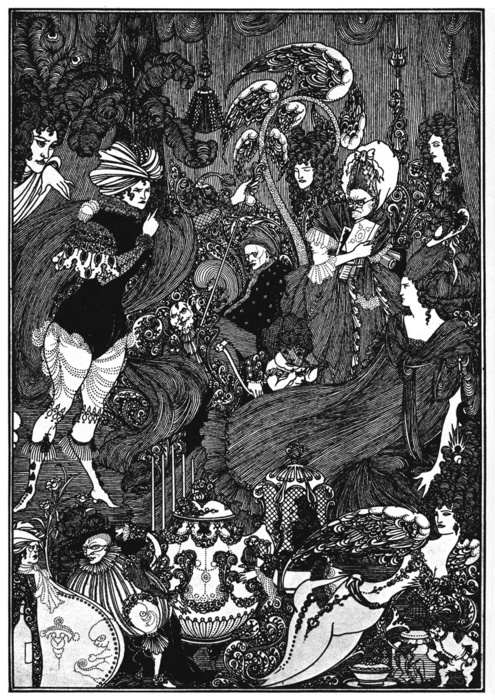

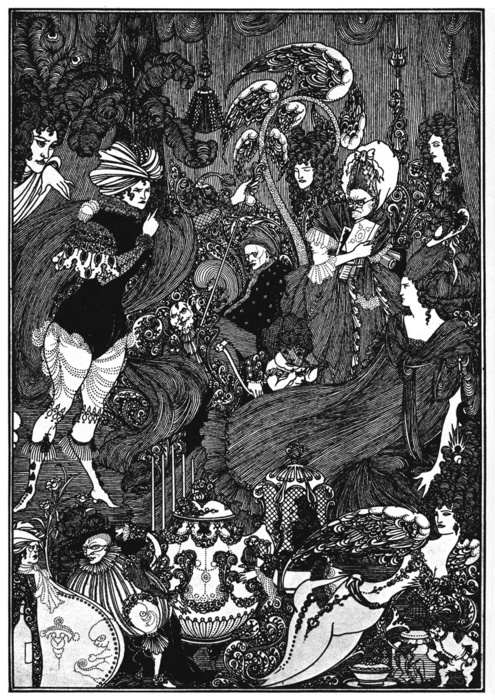

Image Credit: Wikipedia.com

In book three of Pope's Dunciad, the poem's anti-hero intoxicates himself with the plumes (“Popysmata”) of a burning library. From this pile appears the "Goddess of Dulness," who conjures an allegorical vision of four parallel, interconnected hemispheres of censorship. She shows the anti-hero envisions an emblem of the events in book two, in which a popular printers and ideological hacks transfer their Grub Street mores to the center of power. The allegory also foreshadows the philosophical, pedagogical, and religious satire of book four. In this final book, which Pope added fourteen years after the initial release of the Dunciad, the focus shifts from topical lampoons of individual dunces to a general satire on a culture that is oblivious to the limitations of its self-knowledge and the limitlessness of its capacity for imposition. In book two, literature succumbs to a corrupt Grub Street market. In book three, despots destroy and co-opt it. Book four consists of an abstract performance of culture's demise. In the final couplet, Dulness overtakes London: "Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;/ And Universal Darkness buries all" (1743 iv.656). While most critics view this conclusion as the epitome of Pope's gloomy outlook, others suggest alternative ways of reading the poem. Jorge Luis Borges, for example, has approached the poem from the perspective of the allegory in book three of The Dunciad in his essay, "The Wall and the Books."

Image Credit: RhapsodyinBooks.com

In “The Wall and the Books,” Borges discusses the censorship allegory in Pope's third book. He investigates one of Dulness's four agents of literary destruction—Shih Huang Ti [Qin Shi Huang (259–210 B.C.E)], the purported destroyer of ancient gardening manuals and the builder of the Great Wall of China. Borges curiously errs in placing these lines at the beginning of the second book of the Dunciad, since they introduce the ascent of Dulness in book three. Borges's oversight is noteworthy, since his essay consists of one extended meditation on Shih Huang Ti: “He whose long wall the wand’ring Tartar bounds . . . Dunciad, II, 76” (186). Borges writes, "I read, some days past, that the man who ordered the erection of the almost infinite wall of China was the first Emperor, Shih Huang Ti, who also decreed that all books prior to him be burned. That these two vast operations . . . should originate in one person and be in some way his attributes inexplicably satisfied and, at the same time, disturbed me. To investigate the reasons for that emotion is the purpose of this note" (186).

Image Credit: Wikipedia.com

Borges wonders what sublime character might embody the juxtaposition of “walling in an empire” and abolishing its learning. His essay pursues the hidden symmetries between burning books and building walls, and considers Shih Huang Ti’s signifance: “Shih Huang Ti, according to the historians, forbade that death be mentioned and sought the elixir of immortality and secluded himself in a figurative palace containing as many rooms as there are days in the year.” The “magic barriers” of this “closed orb” help Shih Huang Ti halt death by projecting himself into futurity. He is reputed to have said, “‘Men love the past and neither I nor my executioners can do anything against that love, but someday there will be a man who feels as I do and he will efface my memory and be my shadow and my mirror and not know it.’”

Image Credit: Tumblr.com

After pondering historical, dramatic, and metaphorical explanations for Shih Huang Ti's actions, Borges offers his most intricate interpretation: “Perhaps the burning of the libraries and the erection of the wall are operations which in some secret way cancel each other. . . . [Generalizing] we could infer that all forms have their virtue in themselves and not in any conjectural ‘content.’” The harmonies of creation and destruction, he suggests, might reside in transmigrations of a medium. He claims, “Music, states of happiness, mythology, faces belabored by time, certain twilights and certain places try to tell us something, or have said something we should not have missed, or are about to say something; this imminence of a revelation which does not occur is, perhaps, the aesthetic phenomenon” (188). Might "this immanence of a revelation that does not occur" also imply the framework of a satirical juxtaposition?

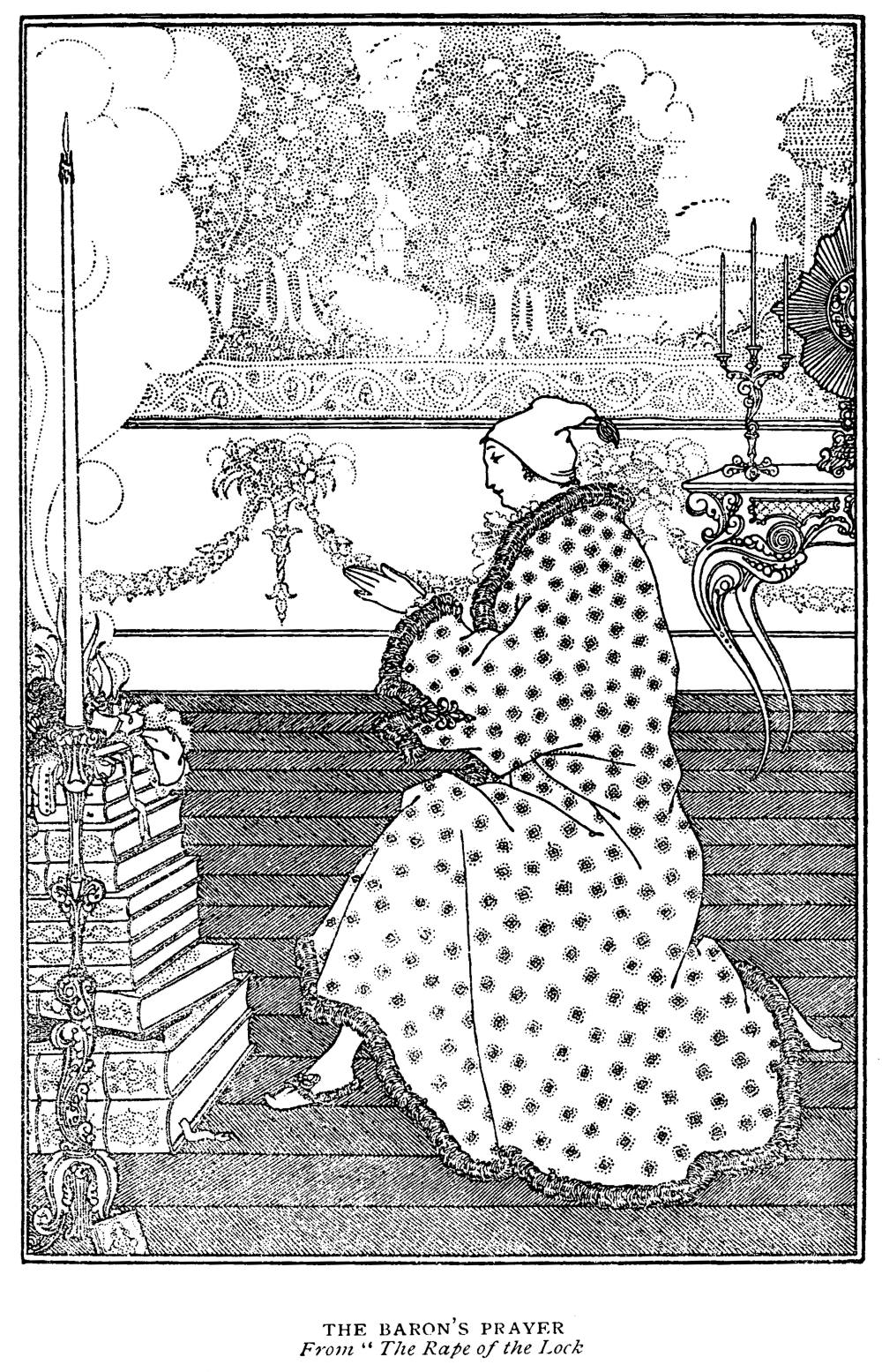

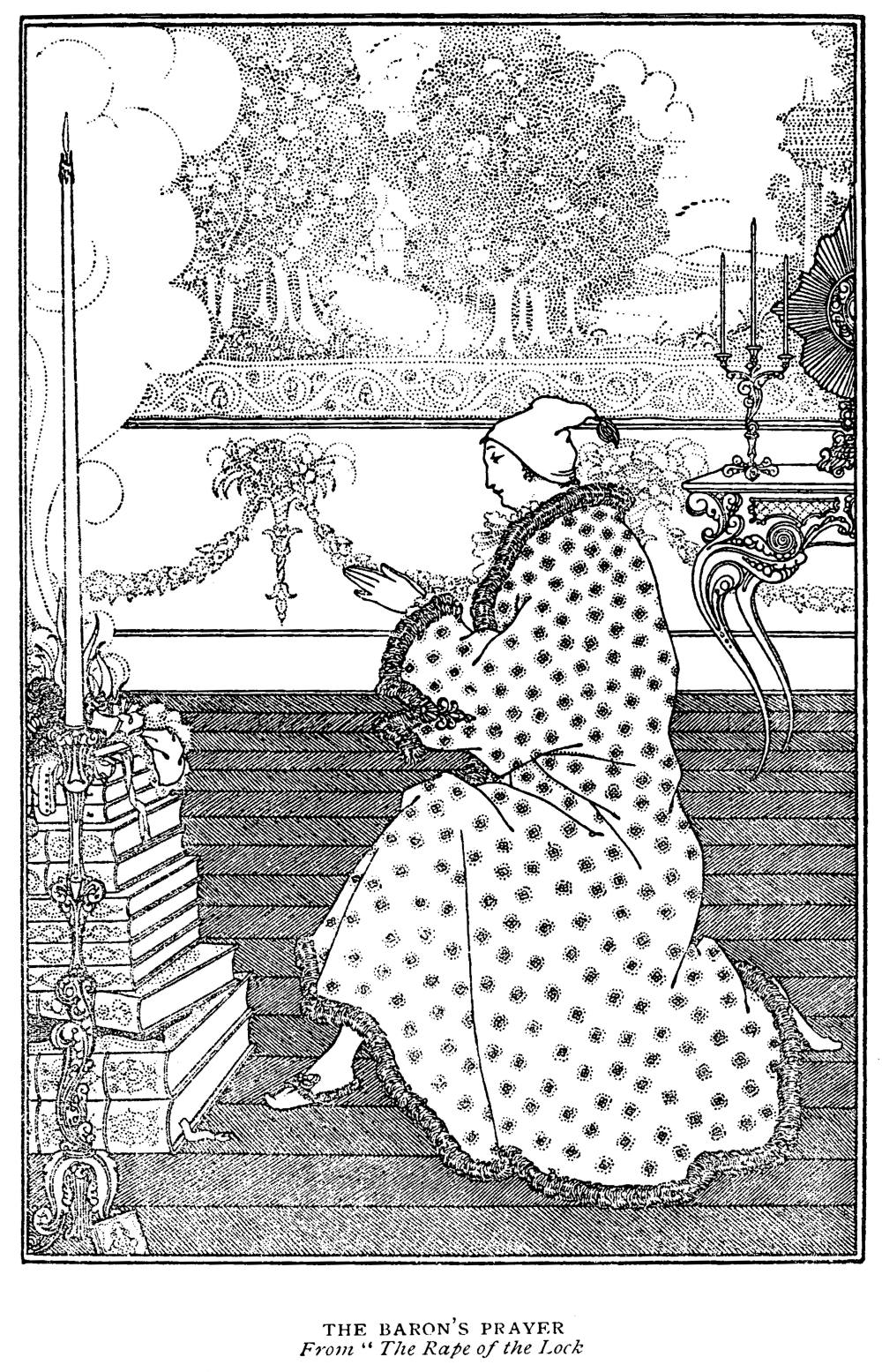

Image Credit: Gutenberg.org

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago