(Image Credit: Time Magazine)

Following on the heels of Megan, Cate, and Elizabeth, I've been monitoring media coverage of the disaster in Japan and coming across some interesting points for debate. I found this Time cover shortly after reading an anonymous letter to Talking Points Memo by a Japanese scholar critiquing Western media coverage of the Fukushima nuclear power plant:

From my perspective as a scholar of Japan at a major American

university―one who was also in Japan when the quake hit (I left one day

later than scheduled on the 13th)―I must say that the coverage was, with

some exceptions, largely substandard: full of factual errors,

misconceptions, and bent towards sensationalism and alarmism. It is very

unfortunate that this poor coverage will probably result in many

Americans having false conceptions of Japan for years to come.

The writer takes the Western media to task, citing several specific examples of inaccurate reporting over the past week, particularly the consistent portrayal of relief workers as desperate and overwhelmed by the enormity of the situation. Conversely, he or she argues that reporting within Japan, "has been largely calm, rational, informed, and critical. Some of this is

naturally to avoid creating panic, but it has been able to do that

because as a whole it has answered many of the questions people have and

thus gained a certain level of trust. As a media scholar, I can pick

this coverage apart for its problems, and of course point to information

that is still not getting out there, but on the whole it is functioning

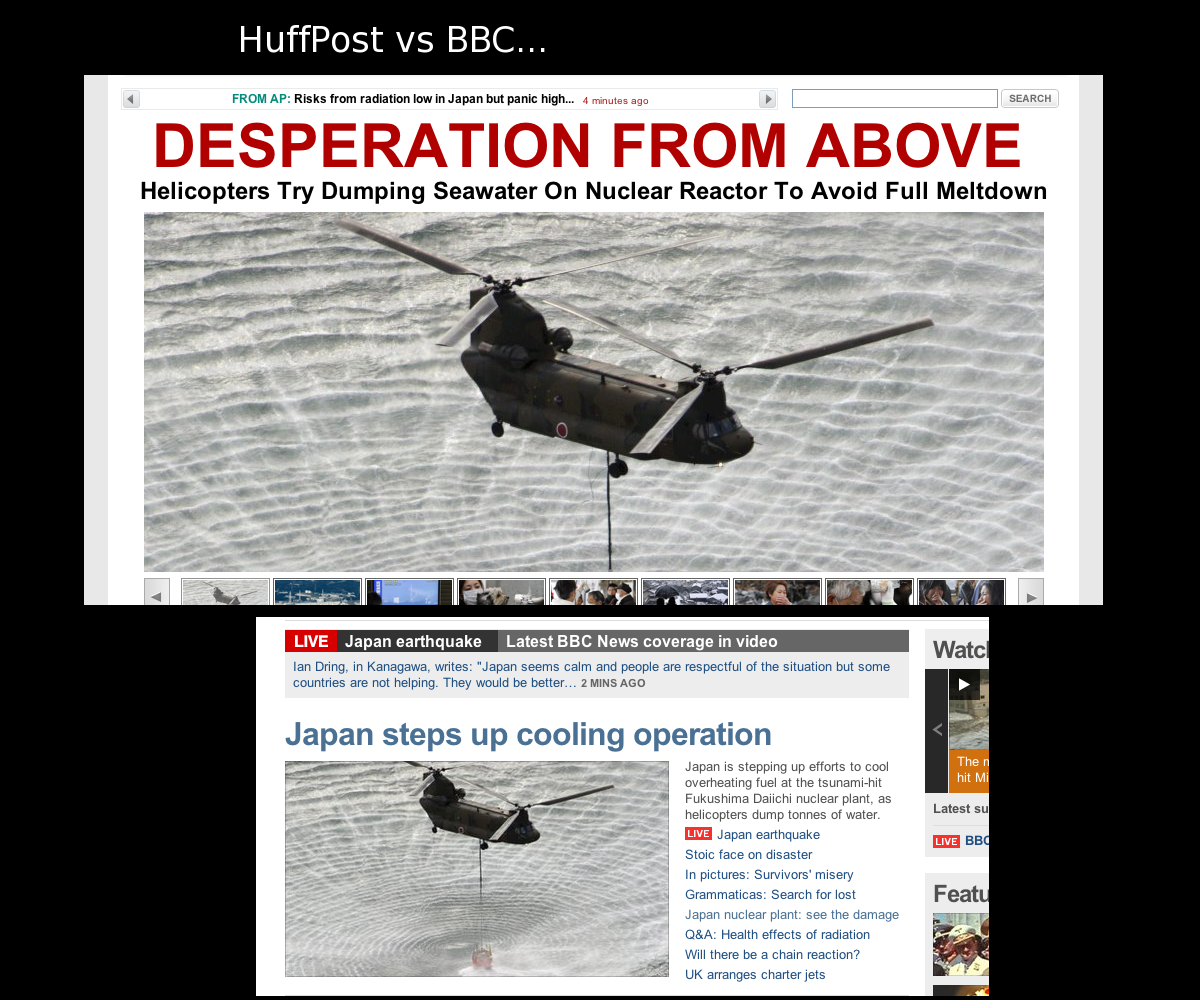

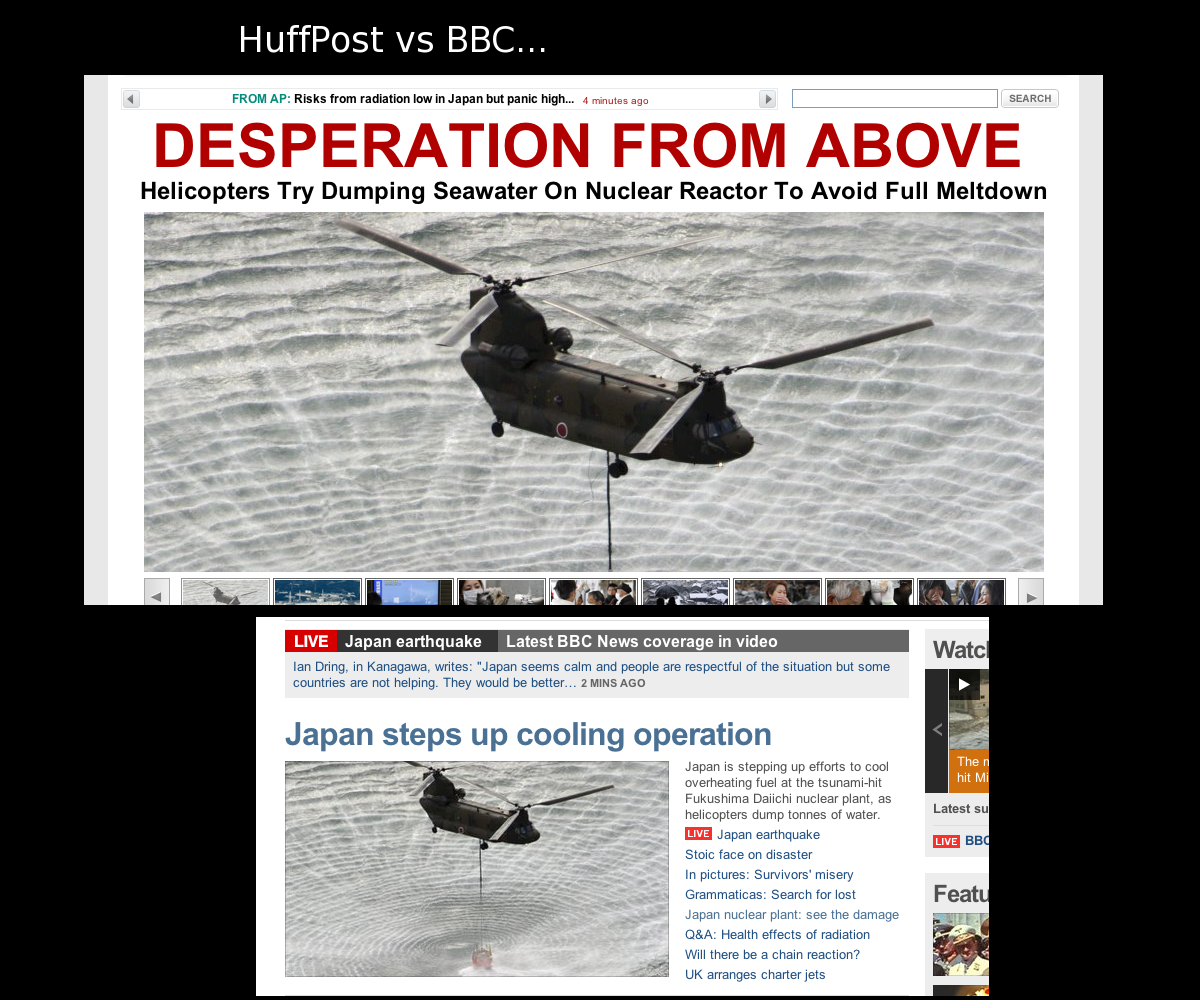

as journalism should." Indeed, Japan Probe's screen caps of coverage of the same event from both the Huffington Post and the BBC reveal that U.S. coverage tends to be more sensationalist:

The letter writer acknowledges that sensationalism sells and notes that foreign journalists reporting from Japan "do not have the language capabilities to access Japanese media," but he or she also argues that

[T]he coverage is rooted in long-standing prejudices held by some

Westerners against the non-West: for instance, a superiority complex

that feels only the West and its media have real access to the truth,

which led to a downplaying of Japanese media reports. In the worst

cases, there has been simple racism, as some reporters when viewing how

calm the Japanese are, seem to think the Japanese are mere robots who

cannot grasp the immensity of the crisis or, as one colleague reports

when a Spanish reporter interviewed her, think that the Japanese are

genetically tuned to accept disaster.

...

But worst of all, the inordinate and sensationalist attention given to

the reactors by American and other media has taken attention away from

where it should be: on the likely nearly 20,000 people who died in the

quake and tsunamis, on the nearly 400,000 homeless people, and on the

immense suffering this has caused for Japan as a whole. I cannot but

think that the low amounts of donations given by Americans to relief

efforts is not at least partially the result of this warped coverage.

Indeed, the nuclear crisis, which at first was merely one of the many destructive consequences of the quake, now threatens to become the entire story. And while the nuclear crisis and its long-term implications for the Japanese are certainly worth attending to, the casualties that have resulted from that particular problem are so dwarfed by the death toll and economic damage caused by the initital quake that I begin to wonder why it has received such a disproportionate amount of coverage. Perhaps it is simply the fact that the quake and tsunami are over and done, while the events and the reactor are a developing story. Perhaps Westerners are simply more interested in the story because it has potential implications for us, as seen in the fact that some people in California have begun taking (entirely unneccessary) iodine tablets and the fact that this disaster has sparked huge debate about nuclear energy in the U.S. (the consequences of relying on coal and oil for energy have been pretty dire in terms of damage to the environment and cost in human lives, but nuclear energy is more mysterious and thus tends to spark more alarm).

Which brings me back to the Time cover (finally). It strikes me that the editors of the magazine are trying to thread a needle here. They are attempting to cover the nuclear crisis while treating it as part of a much larger story, but I'm not sure they are entirely successful. While the photograph of the crying woman does thankfully avoid the stereotypes described above and seems to commemorate the disaster as a whole, I cannot help but be distracted by the headline. "Japan's Meltdown" centers the nuclear power plant crisis in the mind of the viewer and thereby undermines the work done by the photograph and the line "Earthquake. Tsunami. Nuclear Disaster. Resilience."

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago