Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

The Divine Comedy, scene rendering: In a path of blue-white light Beatrice steps down from her chariot to meet Dante, 1921-1930

Norman Bel Geddes lived a sixty-five years that connect two worlds, the Victorian past of 1893, the Atomic Age of 1958. His work reflects and resists that trajectory. The current exhibit on Bel Geddes at the Harry Ransom Center (UT Austin) divides his career into phases or stages of development. A highly creative childhood segued into a successful career as a stage and costume designer for New York Theater. Of all his work—in industrial design, in architecture, in “futurism”--his set and costume design remains my favorite. But in an important sense, Bel Geddes never left the theater.

In his thirties, Bel Geddes painted some wonderful watercolors of his stages and costumes. The famous one is of his most ambitious—indeed wildly ambitious—production of The Divine Comedy. There’s a great story attached to this endeavor. Bel Geddes recounts in his autobiography a period of creative fallow. He had set his desk against a blank white wall, so over-active and confused was his imagination. He says he learned every crack, contour, and bump of that white wall. One day, looking up at one such barely perceivable irregularity of texture, it appeared to expand and swirl. Soon it was a horrible vortex. Bel Geddes rose from his desk, stumbled backwards, crashed against the bookshelf and fell to the ground. As he recovered from this vertigo he recognized that his eyes were fixed on a book that had fallen next to him. It was Dante’s great work. Bel Geddes opened a page at random, so the story turned myth goes, and decided to employ his imagination in a massively scaled, and complete, production of The Divine Comedy.

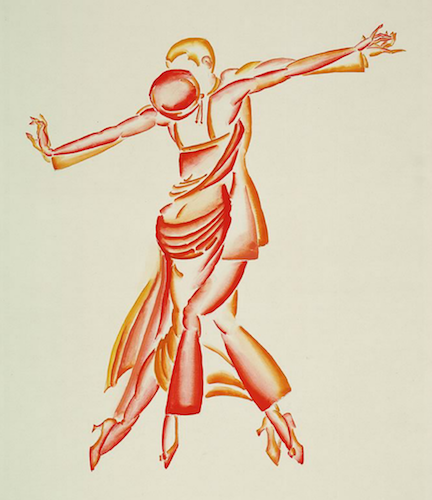

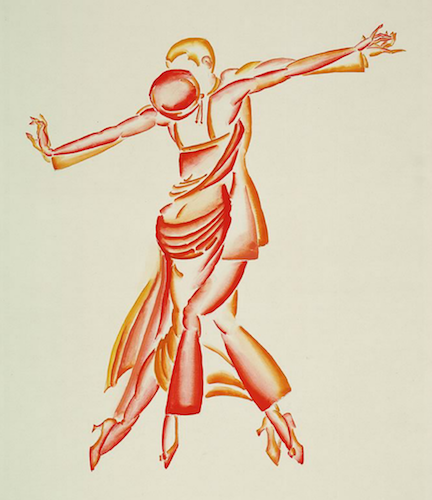

Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

Figures of dancers for Palais Royal Cabaret, 1922.

The watercolors from this period of wonderful creative exertion should strike to the heart of any fan of science fiction, anime, or fantasy. It was in this same foundational period of Bel Geddes creative life that he decorated the Palais Royal Cabaret, one of Paris’s most fashionable spots between the wars.

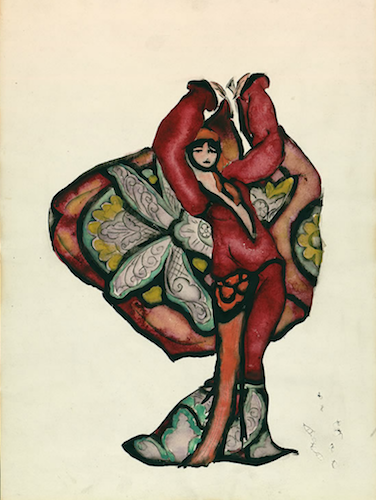

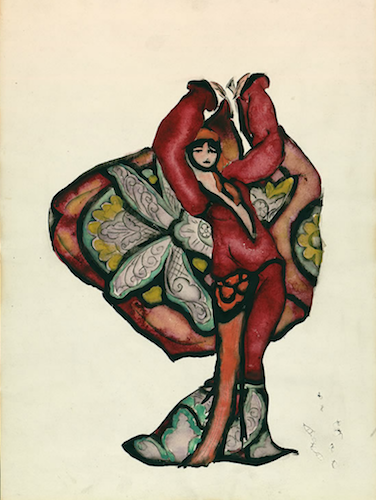

Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

Costume design for Gypsy Woman in The Miracle.

Bel Geddes turned next to industrial and interior design. I find his work of this period—including a range stove that influenced design for decades—understated, sleek, modern. Seltzer bottles for 1939:

Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

In this period, Bel Geddes designed an energy-conserving house, which was less practicable than provocative. Bel Geddes, the stage man, persisted throughout his career.

It was in the booming forties and fifties that Bel Geddes’s ambitions could be matched by material resources. It seems to me that Bel Geddes was better when pressed by limitations. Ambition turns monomaniacal when it is paired with fame—which Bel Geddes had by then come by—and seemingly unlimited resources. Bel Geddes started modeling cars of the future, tanks for the army, a cruise-liner, an ocean-liner of the skies, baseball parks, and of course the Futurama for the 1939 World’s Fair.

Image Credit: GM Media Archives, General Motors LLC.

General Motors, Futurama Spectators, ca. 1939

The massive Futurama could never again be matched. I think Bel Geddes understood that. The works of his middle and old age show a returning humility. Understated Bel Geddes, like understated Dickens, is a rare and fine commodity:

Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

Prototype case for Emerson Patriot radio, ca. 1940-941

Very likely Bel Geddes could not do otherwise than imagine the future. I think there is a sort of futuristic old-fashionedism about Bel Geddes at his best. This style, which shows up in his stage and costume design, in his industrial design, in his home design--should be distinguished from the old-fashioned futurism, the supermans and skyscrapers that dominated the sci-fi pulp, of the 40s and 50s. Bel Geddes is an old-fashioned futurist when he does Futurama. But at his best, Bel Geddes was, I suggest, a futuristic old-fashionist, as in this never-completed plan for the British Imperial Hotel in Nassau:

Image Credit: Edith Lutyens and Norman Bel Geddes Foundation

Job No. 684, Colonial Hotel - Nassau, 1954-1956

Futuristic old-fashionedism: the will to conserve mated with the will to create. One among many strands of the modernist tapestry.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of viz. blog, and are not the product of the Harry Ransom Center.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago