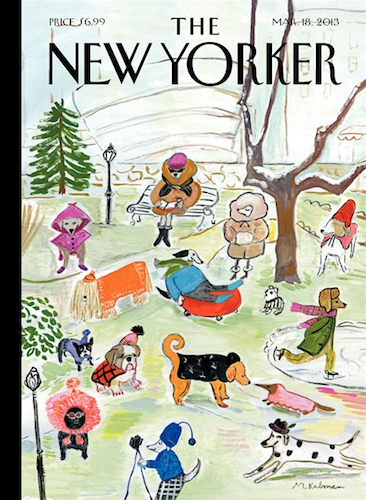

(Image credit: The New Yorker)

This week’s New Yorker cover features a rendering of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, and I thought the occasion merited some meditation on what the museum means to us today. It’s an odd shaped building, and I can’t think of one that’s been built like it sense. Snøhetta’s Oslo Opera House, pictured below and opened in April 2008, is a great example of how contemporary architects are still designing buildings for the arts in brave new ways. (That fantastic structure mimics a Norwegian glacier melting into the sea, and many of its smart features work to invite all of Oslo, not just the operatic elite, to inhabit within and without.) But no structure for the arts built since 1960 has been as original as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum. Opened on 21 October 1959, the Guggenheim Museum is Frank Lloyd Wright’s last masterpiece. It was (more or less) commissioned in 1943, but the project took Wright 15 years and over 700 sketches to complete. Such revision is unusual for a Wright project, of course – most of his designs were completed in a matter of hours. (I suspect he was always thinking about his projects, and thus when the time came to get his ideas down on paper for clients there wasn’t much work to do.) What’s so unique about the Guggenheim Museum is that it’s a descending spiral. This design has two benefits: visitors can effortlessly enjoy the museum’s exhibit as they casually descend a ramp and, more importantly, the changing diameter of the spiral always allows for natural lighting at the art. Form follows function.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago