Image Credit: Harry Ransom Center Photo by Anthony Maddaloni

Near the sorth-eastern quadrant of the Harry Ransom Center is a series of images of a jockey throttling a racehorse: Eadweard Muybridge's "Horse in Motion." While these images may seem inconspicuous juxtaposed to Dorothea Lange's eminently recognizable photographs, their ability to bear witness to a horse's motion was both evidence of an event and a monumental event in itself. The product of two men's obsessions, "Horse in Motion" is both a fascinating example of a visual argument and a foundational episode in the history of motion pictures.

Leland Stanford (left) and Eadweard Muybridge (right) - Image Credit: Wikipedia

As the story goes, Leland Stanford, the railroad magnate who had just helped complete the transcontinental railroad, made a $25,000 bet with a Dr. John D. Isaac about whether there was a moment in a horse's gallop when all four hooves were off the ground. Although the bet never actually did take place, the question at the center of this mythical bet stands in for a hotly-debated question in racing circles. Many observers of horses on the track held to the assertion that a horse would definitely collapse if all of the hooves were to leave the ground at once. Stanford and several others, however, held to the belief that the horse would momentarily be "unsupported transit"--careening through the air with the force of their momentum. Advocates of these theories, however, were at a stalemate because, as Mitchell Leslie points out, "the human eye couldn't pick out enough detail to resolve the issue."

Seeking to put this question to the test and to develop technologies that could help him train and breed better horses, Stanford contacted Eadweard Maybridge, an eccentric but accomplished photographer who was living in San Francisco, to develop a scheme for photographing the horse's gallop in 1872. There was a slight delay, however: in 1874, Muybridge, who had been likened by his contemporaries to a blend between Walt Whitman and King Lear, pled insanity for killing a drama critic who had cuckolded him. With Stanford's help, however, he was found to be both sane an justified. With that little obstacle overcome, Muybridge came up with an intricate scheme that would prove to be a watershed moment in the history of film.

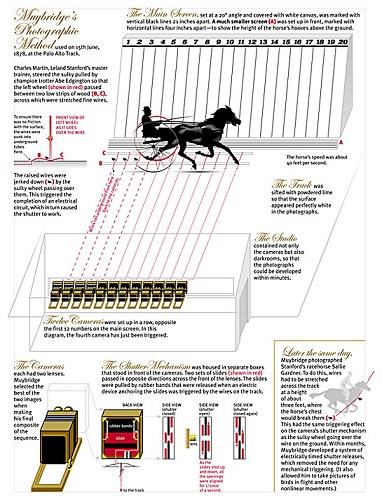

Image by Nigel Holmes: Stanford Alumni Magazine

In July of 1877 and June of 1878, Muybridge set up complicated photographic rigs to capture images of Stanford's horses at racetracks in San Francisco and Palo Alto. As the image above demonstrates, Muybridge laid out a series of cameras that were parallel to a horse's path. And as the horse would run across the course, it would set off a series of tripwires that would set off these cameras. He also succeeded in developing a method of capturing an image with a shutter speed of less than a hundredth of a second--a technique that would assure a crisp image of the horse's movement. By capturing this series of images at split-second speed, he was able to definitively prove that horses did indeed fly through the air mid-gallop.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Using a spinning Zoopraxiscope--a device that Muybridge invented--the photographer and inventor was able to mass-produce his discovery, presenting the series of images on a disc that was meant to spin like a record. A viewer who kept her eye on the bottom image would get an illusion of motion like this:

Image Credit: Wikipedia

Fifteen years after capturing these iconic images, Muybridge set up an exhibit in the 1893 World's Fair that shared his discoveries to an even wider range of spectators. Brian Clegg, author of The Man Who Stopped Time, has called this the first commercial movie theater!

Comments

Have you checked Google today?

Muybridges just got a Google Doodle for his birthday today! Great time to read this post again, Ty!