.jpg)

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Over the past summer, I spent a month as a Gest Fellow at Haverford College’s Quaker & Special Collections, where I was researching an eighteenth-century female preacher. The most entertaining and unexpected find over that month pertained to an image archive classified as “Anti-Quakeriana.” One of the more interesting aspects of Quaker history (in my opinion) is their retention of documents released by rivals and detractors. Hence the origin of the classification, “Anti-Quakeriana.” As a result of such practices, scholars and historians now have an archive rich in cultural contexts and historical negotiations that mark the transitions from a seventeenth-century “schism” to an eighteenth-century “sect.” Below, I briefly discuss a series of paintings and engravings of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century female ministers.

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Above is an oil painting by Egbert Heemskerk—the seventeenth-century Dutch artist who would inspire a veritable genre of anti-Quaker iconography. Notice the female preacher cloaked in the foreground, distinguished by her witchy hat. I am grateful to John Anderies, a librarian at Haverford’s archive, for directing me to Heemskerk’s painting as well as the archive of caricatures of his painting, “A Welsh Prayer Meeting.”

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

In his recent book, Italian Opera in the Age of the American Revolution, Pierpaolo Polzonetti situates the following images of female preachers “at the borderline between parody and realism, comedy and mockery, disparagement and admiration” (228). On the other hand, Harry Mount argues that Heemskerk’s paintings themselves are “anything but satirical.” Haverford holds a framed original of Heemskerk’s oil painting, entitled “Quaker Meeting,” which is quite striking (the initial image of this post is a photo of a black and white reproduction). Whether satirical or sincere, Heemskerk’s paintings inspired a surprising number of parodies well into the eighteenth century. I cannot help but thinking these may have inspired Daniel Defoe’s misogynistic pronouncement—that women ought not be depicted singing or speaking, for unless “the other Passions discover it, she may as well be supposed to be swearing, scolding, sick, or any thing else, as well [as] singing.” Despite his numerous connections with members of the Society of Friends, Defoe wrote against their embrace of pacifism and female preaching, their attacks on bibliomancy and baptism, their repugnance to oaths and critiques religious rationalism.

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Each of the images in this post has been reproduced from Haverford’s extensive archive of “Anti-Quakeriana” (a small selection of their much broader Quaker and Special Collections). These images reflect the negative bias Defoe articulates, but they diffuse the content of Quaker female ministry into caricatures of the overall affective and social contexts of religious gatherings. The integration of the preacher (foreground) and meeting (background) suggests that these artists are using female speakers as a paradigmatic representatives of the group. Women had been prominent and active in Quaker communities since the Society of Friends was founded in the mid-seventeenth century. Margaret Fell, the preacher featured above (left), was both a minister and the manager of traveling funds at London’s primary “Bull and Mouth Meeting House” (the scene above). Her husband, George Fox (standing right), is often considered to be the founder of the Quaker Society of Friends. As Haverford’s archive of “Anti-Quakeriana” makes clear, many of the early representations of Quakers stressed the unique role of their female preachers as the most distinctive characteristic of the group.

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Image Credit: Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections

Engraved imitations of Heemskerk's paintings tend to emphasize the social nexus of Quaker female ministry. The three images above demonstrate slight shifts in emphasis. Isaac Beckett’s 1681 engraving portrays an intensely subdued preacher, whose quells the audience into a meditative silence. Marcel Lauren’s engraving (middle) turns to caricature by foregrounding the transports of an enthusiastic (almost terrified) man in the audience. In Carolus Allard’s 1706 copper engraving, the female preacher reigns over a dubious scene. Cats snarl in the alcoves, and the group skulks about without sharing a single sightline (other than those who address the viewer). Given such imitations, one might imagine British Quakers as participants in the frenzy of the more widespread “Great Awakenings.” In fact, eighteenth-century Quakers were generally less outspoken and controversial than their seventeenth-century predecessors had been. While these caricatures of Heemskerk may appear anachronistic, they also represent a shifting concern with the Quakers’ progressive (and principled) negotiations of gender norms, and their encouragement of female participation in the public sphere.

Image Credit: Haverford College Special and Quaker Collections

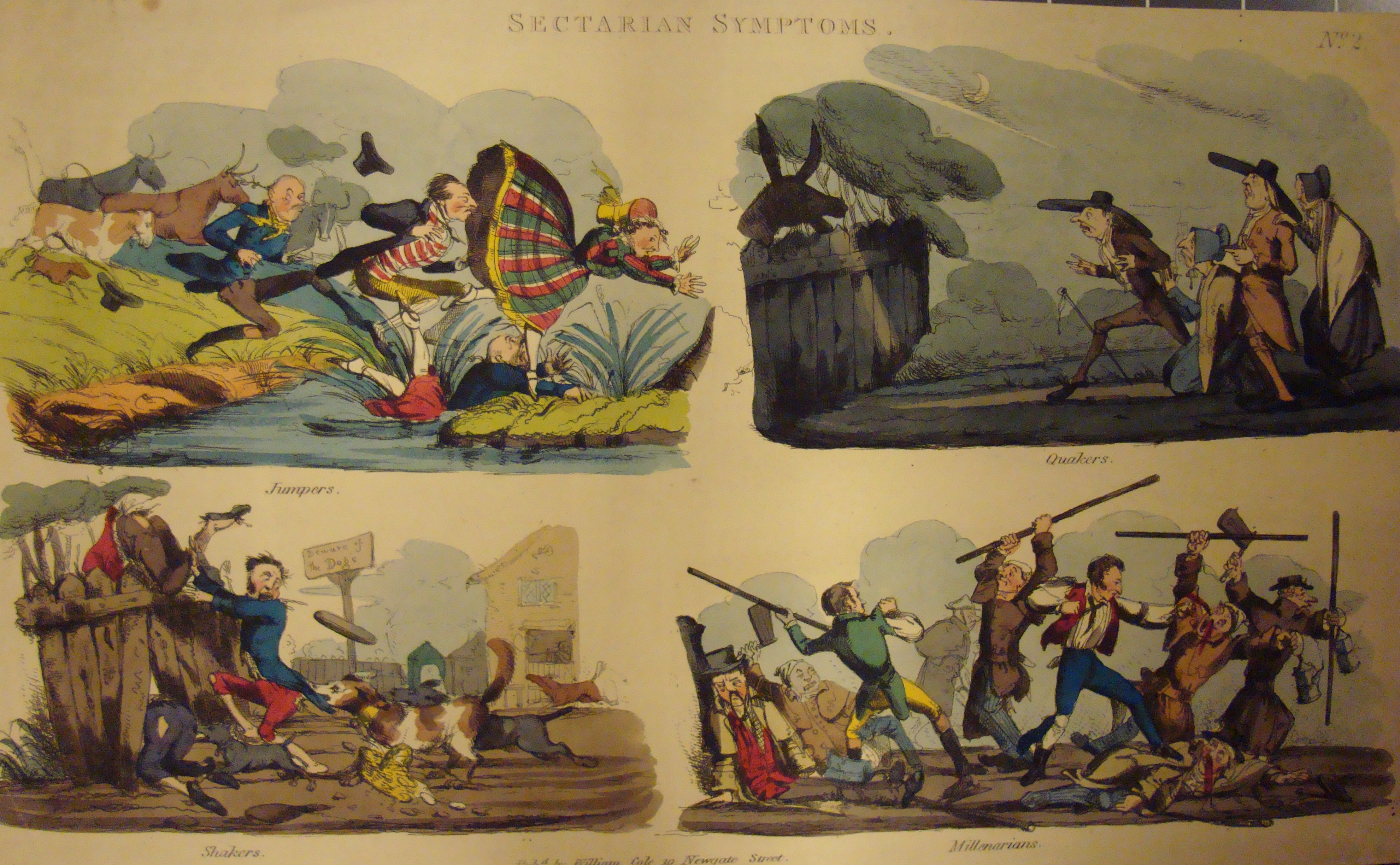

Above is one of my favorite images from the archive of "Anti-Quakeriana"—William Cole's "Sectarian Symptoms."

Top left: "Jumpers"; Bottom left: "Shakers"; Top right: "Quakers"; Bottom right: "Millenarians"

I would like to thank John Anderies (the head of Special Collections), Diana Franzusoff Peterson (Manuscript Librarian & College Archivist), and Anne Upton (Quaker Bibliographer & Special Collections Librarian), and the undergraduate staff for their invaluable help over the summer.

Works Cited

Pierpaolo Polzonetti, Italian Opera in the Age of the American Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2011).

Harry Mount, "Egbert Van Heemskerk's Quaker Meeting Revised," Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 56 (1993): 208–28.

Comments

Witchiness

My question is where the characterization of witchy comes from. Is it just the visual reference, or is there other information (say from the librarian there) that this hat was viewed at that time as akin to witches' garb? In the second to last picture there seem to be others with the hat, and at least one seems to be a man. Quakers at the time wore hats/bonnets--could this depiction be about the gender roles as well? That is, is the hat a sign of maleness or male power, taken on by a female? (The higher the hat the closer to God :) ). Or could it have been the artist's way of making fun of Quakers by commenting on their odd attire?

I appreciate your comments about the lack of focus in many of the pieces. As a Quaker, I can imagine an outsider looking at a Friends' Meeting and thinking no one was leading, no one was focused properly on a powerful (read: male) Christian center.

VERY interesting find, I'd love to see more posts on this.

Sarah Wagner

Witchy Hats

Hi Sarah,

Thank you for your comment. The "witchy" reference derives in part from several other images, which portray the women conversing with demons. I didn't post these, because one seemed plenty. The literary anti-quakeriana of the period also brings out the "witch" trope pretty forcefully. Lodovic Muggleton does this in really interesting & weird ways. Finally, I was also thinking back to the more extreme attacks on female preachers (esp. Mary Dyer's hanging in Boston) during the seventeenth century. In retrospect, I might have chosen a less negative term, but the intent was not to stigmatize. I agree with you that there is something interesting going on with the hat. I've withheld my favorite of the images from the post, but the preacher has a distinctive hat and is especially cool & assertive. There must be some correlation here. In the pictures of 18th c. quakers I've seen, the women seem to mostly wear bonnets (even prominent ones). Green seems to have a big color, according to letters. It was in to wear clothes one or two generations behind the fashion trend, but I think that pointy hats were well out by the time of the prints (maybe not the original). If you find any info on what hats were popular when, I would be really happy to know!

-Matt

Witchy hats

Just to say that the 'witchy hat' also has a close resemblance to the black, tall, Welsh woman's hat popular at the time and a form of which remains part of Welsh national dress. Hence, unsurprised to see a Welsh meeting with such a woman. Of course, everything you have to say about 'witchy' references to Quaker women in anti-Quaker literature is quite right and illuminating. Just a thought though.

Right up my alley

Dear Matt:

You've discovered a treasure trove, and your analysis is very helpful for understanding it. I wonder how it lines up with other kinds of misogynist ("witchy") depictions of women in the print culture of the period. You and Kevin Bourque need to compare archives! Thanks for this.