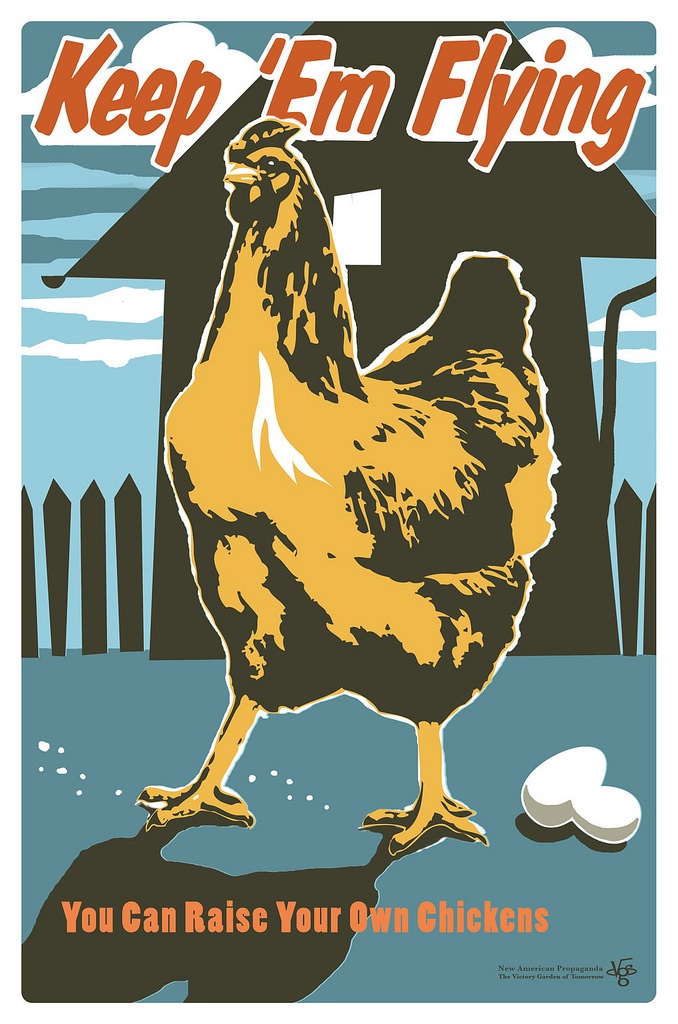

Image Credit: Joe Wirtheim

In the interest of full disclosure, I must confess that I have always had a soft spot for "victory gardens" and mid-century propaganda. It may be a result of the countless times I watched Bugs Bunny steal carrots from the Saturday-morning victory gardens of my childhood (how many of us were introduced to serious political concepts like shortage, rationing and military conscription through the Flatbush intonation of Mel Blanc?). It may have been the vintage singns and posters ("Loose Lips Might Sink Ships") hanging on the wallls of the local burger joint that was a favorite haunt of my grandfather. Whatever the reason, my eye is always drawn to the bold fonts, severe angles and jingoistic slogans of WWII era posters, particularly those aimed at action on the home front. This week, while trolling for vintage design and espirit d'corps, I came across "The Victory Garden of Tommorrow," Joe Wirtheim's modern day art/propaganda campaign that repurposes and reinvents the genre. More on Wirtheim's project, refurbished propaganda and mobilizing the population after the break.

Wirtheim describes his work as "an art project posing as a propaganda campaign for new, American

homefront values. The message style draws from American mid-century

homefront propaganda, and the messages essentially draws from 21st

century needs as found in the current environmental sustainability

movement. The campaign is designed to access America’s history of

ingenuity to overcome adversity, and apply those values to fighting

modern problems." Wirtheim does much more than repackage or redeploy turn of the century images. He borrows from the iconography of the era, and simultaneously participates in the urgency of the earlier propaganda and gives us a wink through their campiness. Compare Wortheim's "Break New Ground" with this New Zealand contribution to Great Britain's "Dig for Victory" Campaign.

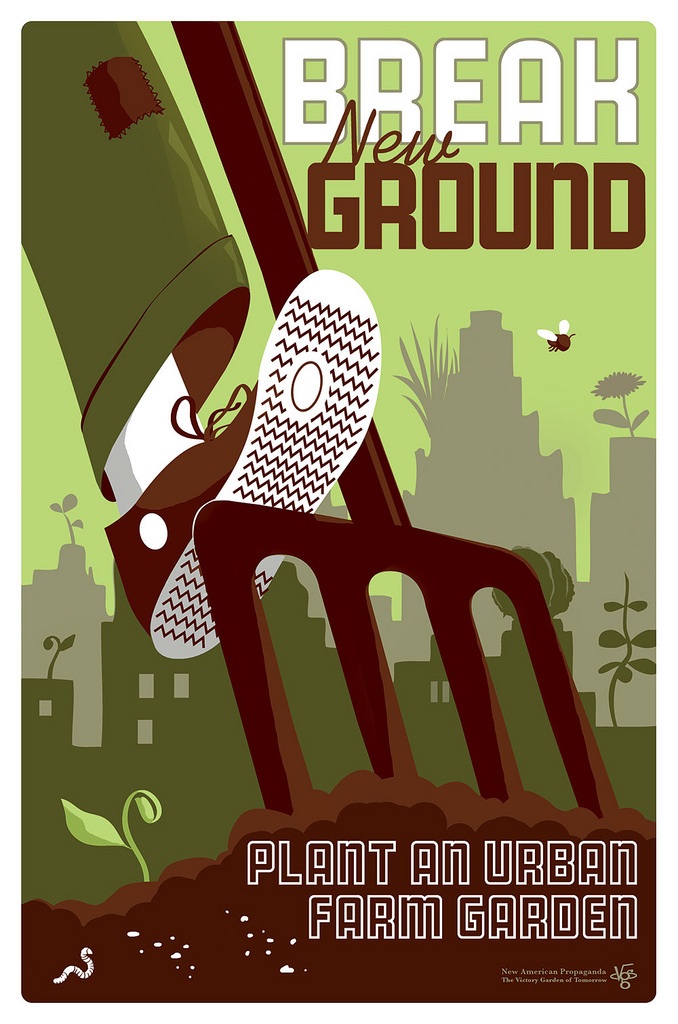

Image Credit: Joe Wirtheim

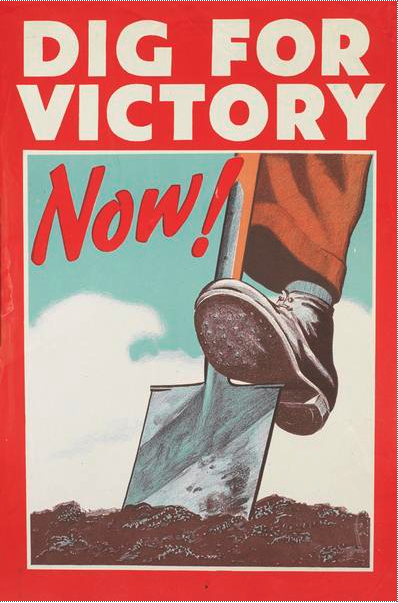

Image Credit: Imperial War Museum

While the pitchfork and foot in "Break New Ground" are certainly an homage to the British series, Wirtheim has translated the poster's wartime austerity into a new aesthetic register. The posters share essentially the same goal-- they both want you to start growing your own food-- but they rely on substantially different rhetorical appeals. The paucity of the British campaign is well suited for an audience facing the shortages, rationing and hardships of a protracted war. There are no unneccesary embelishments, just the bare earth, the blank sky and the task at hand. It resonates with both the English stiff upper lip and the mid-century penchant for martial drama.

Wirtheim's poster presents another argumenta altogether. His cityscape teems with life as plants sprout not only from the ground but (prophetically) from every roof on the skyline. As urgent as America's food crisis may be, Wirtheim isn't speaking

primarily to people who are confronted daily with scarcity and want, so he

presents growing your own food as an inviting pleasure rather than a stern duty. (The Chuck Taylors give us a pretty good hint about the range of his intended audience). The friendly-looking worm (who appears to have stopped by to watch the digging and chat with us) and the plump little fly add a playfulness and whimsicallity that would be entirely inappropriate in the British campaign, but they are pitched perfectly for an urban gardening movement that idealizes compost and earthworms. The brown-and-green palette reinforces the "dirt and plants" focus of the poster and fit within a recognizable iconography of organic farming and environmental awarness. The patch on the trouser leg makes a subtle argument about living a non-consumer, environment friendly lifestyle that borrows from the WWII era concern with scrap, necessary trips and "making do" in general (a sentiment that was sadly not shared by the Bush administration that encouraged Americans to buy on credit while it began borrowing heavily to finance two foreign wars).

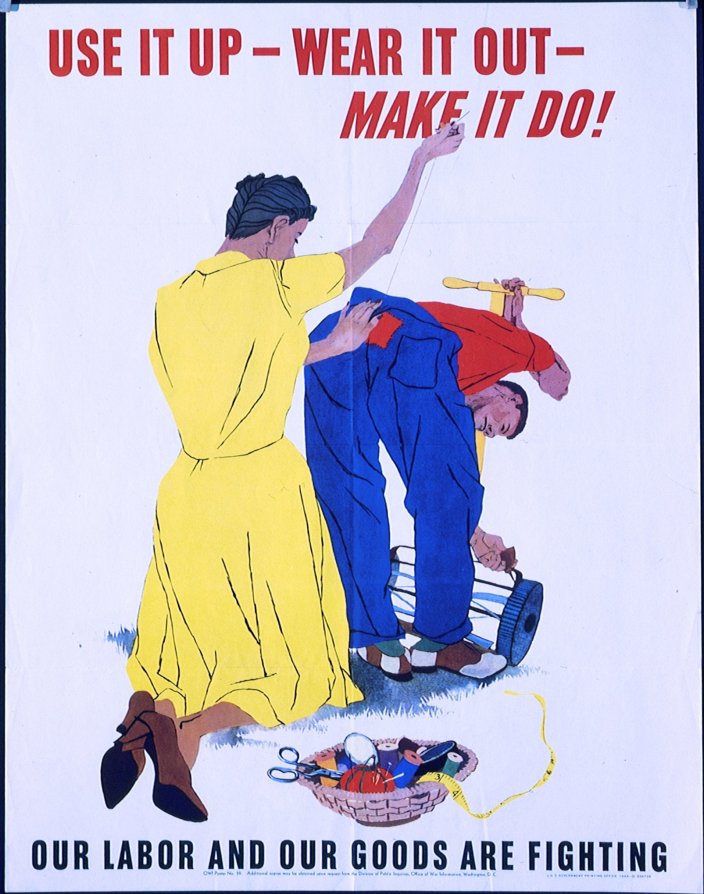

Image Credit: NH.gov

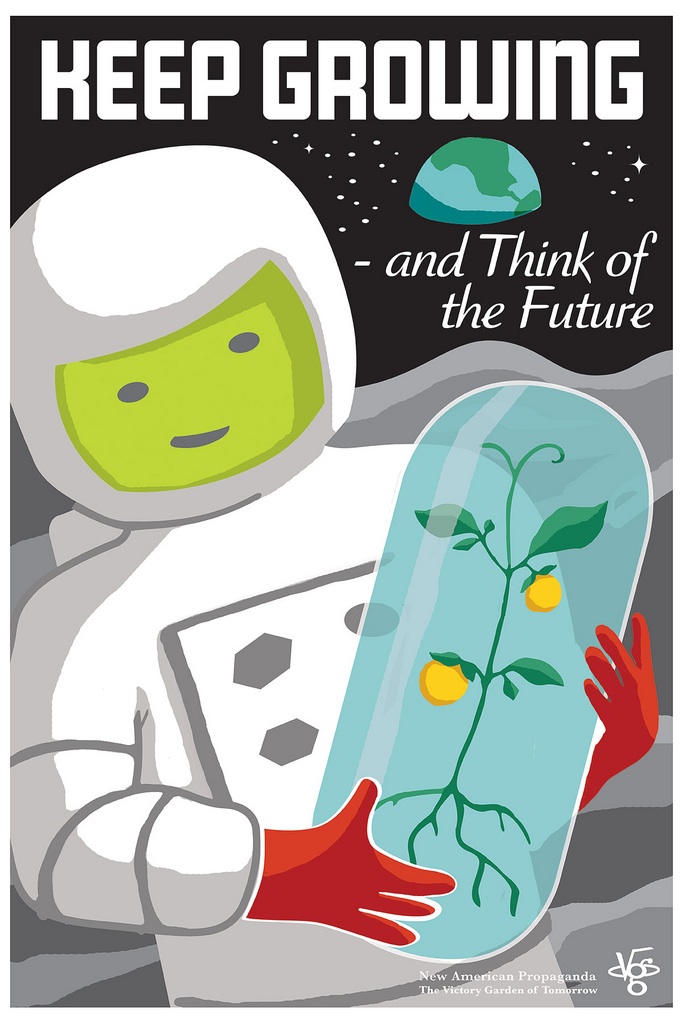

Wirtheim also borrows from post-war iconography to craft his new American propaganda. His project is, after all, not just any victory garden: he presents the Victory Garden of Tomorrow, and several of the posters draw heavily on the campy futurism of the 1950s and 60s. As he does with the war posters, Wirtheim updates and revises the images while holding onto a tongue-in-cheek version of the original sentiment (in this case, unbridled Jetson-esque optimism).

Image Credit: Joe Wirtheim

Image Credit: Joe Wirtheim

This last poster works in yet another iconic image and emphasizes Wirtheim's conscious connection to the environmental movement. Over the shoulder of the Meyer-lemon growing lego-spaceman, Wirtheim includes a version of Earthrise, a photograph taken by William Anders on the Apollo 8 mission and often viewed as one of the single most galvanizing images of the environmental movement.

Image Credit: NASA.gov

Earthrise reminds us in dramatic fashion that our earth is a tiny island home in the cold, dead vastness of space. Wirtheim's image--a mix of space-age camp and environmental realism, reminds us that (since none of the mid-century dreams of space colonization by our century have panned out) the way we grow our food-- and the way we treat the earth in the process-- has lasting effects for us as individuals and for the entire planet.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago