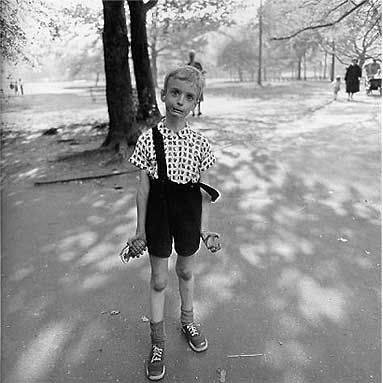

Image credit: Diane Arbus

As part of the final project for our “Rhetoric of Social

Documentary” class my students will be completing a brief documentary film on a

local issue and so we spent this week talking about the ethics of documentary

filmmaking and the discomfort many people feel in having their picture

taken. We began the class with a

discussion of Susan Sontag’s chapter “America, Seen Through Photographs,

Darkly” from On Photography in which she

considers the work of Diane Arbus and the shift in photography away from lyrical

subjects toward material that is “plain, tawdry, or even vapid” (Sontag,

28). Sontag explores the artist’s

decision to focuses on people she terms “victims” or “freaks” and argues that Arbus attempts to suggest a world in which we are all isolated

and awkward.

One of my students seized on Sontag’s argument about Arbus’ awkward depictions of her subject and suggested that feeling awkward while having a

portrait made is common to all of us but that looking awkward in a portrait is

seldom the goal of the sitter.

This comment led us to consider whether Arbus might be exploiting her

subjects or, at the very least, seeking their least flattering image amongst

many shots in a series. As a

class, we discussed the photograph of the child above with respect to the issue

of consent from the people we photograph.

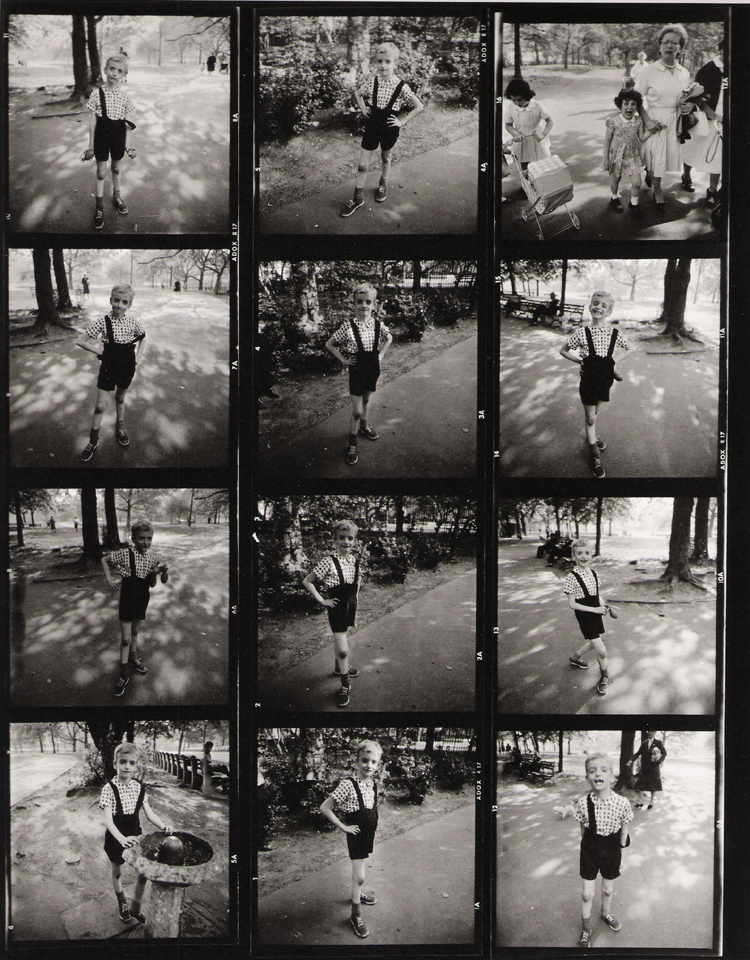

The question of consent, however, brought us to question what it might mean

to depict our subjects in a manner at odds from their own desired

self-presentation—we looked at the contact sheet that shows the many portraits

from which Arbus might have chosen and compared these to the one she did

select.

Image credit: Diane Arbus

The relationship between the intentions of the person

photographed and the photographer is a sticky one for documentary filmmakers

and my students grappled with how to balance the ethics of taking someone’s

picture (or mercilessly editing someone’s interview—we looked at some Michael

Moore footage) with the goal of making an argument about a social issue. Sontag reminds us that the camera can

function as “a kind of passport that annihilates moral boundaries and social

inhibitions, freeing the photographer from any responsibility toward the people

photographed”—a claim that my students really struggled with in our discussion

of ethical image-making.

Posing for a photographic portrait is always uncomfortable. Barthes notes the anxiety that

accompanies this experience and argues that in the act of posing, before the

photograph is even taken, "subjects transform [themselves] in advance into an

image" (Camera Lucida, 10). As a class, we considered the differences between posed portraits and snapshots and the possibilities for accounting for the goals and preferences of our subjects. Arbus’ snapshot portraits seem as

uncomfortable as her static posed compositions. There seems no guarantee that the photographic genre will

protect the wishes of those photographed. In fact, in many cases of social documentary the

larger argument is in direct conflict with the desired self-representation of

the subjects. Tricky territory

here for my students and I am looking forward to watching them craft their

larger rhetorical claims while keeping in mind the ethics of image-making.

Comments

always already outside our control

And, of course, one of the definitive characteristics of the photograph is that it exceeds and escapes our desire/ability to control it. In order for a photograph to be what it is-- a replicated image capable of existing apart from the thing it figures-- it must be separable and therefore always (at least potentially) separate from its subject. If our image in the photograph-- its appearance, its circulation, the manifold intentions of photographers, subjects, viewers, students, academic bloggers, etc.-- were subject to or dependent on our presence or intentions, then it would not be the kind of thing that exists apart from us and could not survive our absence. This is, of course, why (as numerous theorists of the photograph have said) the photograph always includes our death. It is a thing that by its nature exists apart from us and can continue to exist after us, and its necessary independence and durability presuppose our mortality. In similar fashion, the very form of the medium also presupposes that it will not and never could protect the wishes of those being photographed.