The New York Times has an article on architects Jeremy Fletcher and Alejandra Lillo of Graft, who have designed a new condo tower in Manhattan, the W Downtown, with glass walls. According to Fletcher and Lillo, the purpose of the see-through design is to “[work] out a dialogue between voyeurism and exhibitionism”:

Not only will the building’s glass walls allow W residents to see, and be seen by, passers-by on the street below, but Mr. Fletcher and Ms. Lillo have created peekaboo features within each apartment, like a window between the kitchen and the bedroom, and a bathroom that’s a glass cube, allowing residents to expose themselves to their roommates and family members, too. The idea, Mr. Fletcher said, was to frame and exhibit the intimate details of life, or at least ones that would be aesthetically pleasing, “like your silhouette in the shower.”

My first thought when reading this piece was that if someone wanted to expose his or herself to a roommate or family member, it could be done without peekaboo windows. More germane to this blog, I find the focus on performance to be very interesting. The author of the article, Penelope Green, connects this trend in architecture to Facebook and YouTube, where users regularly “expose” the intimate details of their lives for all the world to see. The difference between the two, Green points out, is that the information users post to these sites is “conscious,” that is, carefully chosen and scripted to present an image that the user wants to project, while the mundane details of day-to-day living is “unconscious.” Fletcher points out that his and Lillo’s design is open to the kind of careful choreography available online:

“We are creating stages for people to perform on in some way, but it’s a very scripted and considered display,” he said. “Cooking could be a display, for example, with your partner watching you from the bedroom.”

He talked about tuning the privacy of each room, using shades or scrims to have larger or smaller openings, as you would change the aperture of a camera. “So if you don’t want your partner to see you shaving your legs in the shower,” he said, “you can pull the shade.

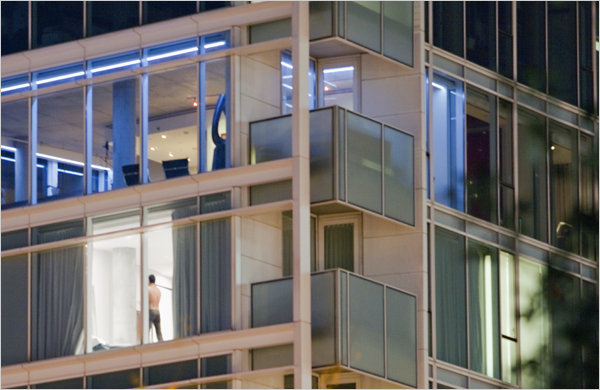

However, the reality of living in a glass house seems more likely to lend itself to this experience:

In September, Curbed, the feisty New York City real estate blog, posted a photograph of a newly completed, glass-walled condo building on East 13th Street. You could see right into the apartments, which looked most like messy dorm rooms. It was a grubby retort to the marketing hoo-ha that surrounds these now ubiquitous buildings and trumpets a sleekly attractive lifestyle accessorized by midcentury modern furniture and designer clothing. There were unmade beds jammed right up against the glass, mangled paper Venetian shades, a towel over a chair.

The article then ventures into questions of what we will do if we have to perform all the time, without having a private retreat to some place where we can drape our towels with abandon. It’s an interesting read.

Comments

The questions about

The questions about perpetual performance and the dissolution of Goffman's backstage spaces is interesting, but the real question I think the building begs scholars to answer is what happens to the categories of exhibitionism and voyeurism when those brands of showing and watching are no longer intentional violations but conditions of everyday life. Maybe that's the building's point, but when the friction of violating a norm is removed, when voyeurism and exhibitionism aren't transgressions against decorum but a mere fact of living, it seems that we come close to giving a semi-legitimate name to a totalizing and potentially oppressive surveillance.