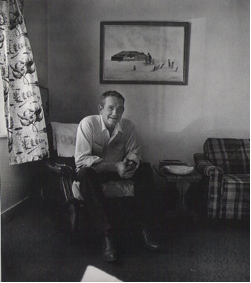

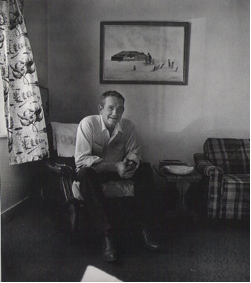

Image credit: Bill Ganzell

A few weeks ago I posted about rephotography projects—after

thinking through some of the issues surrounding these images I began wondering

why so many of these rephotographic projects appeared in the 1980s. Two texts in particular caught my

attention: Bill Ganzell's 1984 Dust

Bowl Descent, and Michael Williamson and

Dale Maharidge's 1989 And Their Children After Them.

Ganzell rephotographed several of the same images captured by

documentary photographers during the Great Depression while Williamson and Maharidge

retraced the steps of Walker Evans and James Agee for their 1936 photo-text Let

Us Now Praise Famous Men. Taken decades after the initial

Depression Era images, these rephotography projects of the 1980s are a record

of change.

I suppose it is not surprising that the rephotographers of

the 1980s took up their cameras just as it became clear that the earlier

historical moment of the New Deal had disintegrated. The decades between the ‘thirties and the ‘eighties saw a

gradual decline in the influence of unions, the crumbling of the liberal-Left

coalition, and a turn towards conservative politics and policy that favored the

wealthy at the expense of the poor.

The decline of this "New Deal Order" is linked, according to

Gary Gerstle's The Rise and Fall of the New Deal Order with the ascendancy of the Reagan administration.

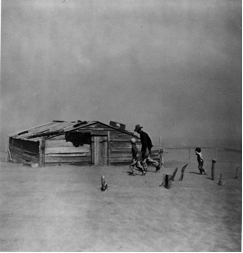

Image credit: Arthur Rothstein

Image credit: Bill Ganzell

Ganzel tracked down and rephotographed several of the same subjects and shots of earlier FSA photographs. He animates several of the earlier FSA images, solving problems suggested in the photograph. The power, for instance, of Arthur Rothstein's photograph "Fleeing a Dust Storm" comes from the viewer experiencing these subjects frozen in an uncertain moment where survival seems less than inevitable. James Curtis in Mind's Eye Mind's Truth (and more recently, Errol Morris) points out that Rothstein manipulated the circumstances of this situation in order to capture a more dramatic event. When Rothstein took this image there was no rising dust storm to flee and he staged his subjects in front of a dilapidated storage shed rather than the home where they actually lived because the smaller, more rickety structure increased the seeming precariousness of the situation. Darrel Coble, the youngest child falling behind his father and brother in Rothstein's 1936 photograph, is rephotographed by Ganzel smiling and sitting safely in his home, a copy of the FSA picture framed behind him on the wall. Ganzel seems to find a way to visually alleviate the tension within the first image and, perhaps, alters the rhetorical and political impact of the earlier photograph through the rephotograph.

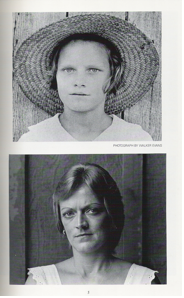

Image credit: page from And Their Children After Them

Michael Williamson, Dale Maharidge, Walker Evans

Williamson and Maharidge construct Children After Them with exactly the same format as Famous Men. In

their layout of the images—the original above the rephotograph both on one

page—Maharidge and Williamson convey a sense of the passing of time. The photograph and rephotograph of

Maggie Louise Gudger shows the same woman standing before a wooden structure at

two points in her life almost fifty years apart. Although this reimaging suggests that Maggie Louise is still

a victim of poverty and in need of aid, this second photograph evokes a kind of

stasis. It is as though she has

been silently standing there all this time. Maggie Louise stares hauntingly back at the viewer with a

similar expression to that in the earlier image of her as a child. The implication is that this woman is

still living an uncertain life of fear and poverty. Maggie Louise certainly had her own motivations for posing

for this photograph, however, Williamson's decision to portray her exactly as

Evans had in the 1930s robs her of the opportunity to convey any of that

agency. She simply seems trapped,

stuck in the same place and socio-economic situation as fifty years

earlier.

I am curious as to how we should read these

rephotographs—are they jeremiads calling the audience to reinvest in the effort

to end poverty or evidence of the ultimate success of New Deal reform efforts? Ganzell’s visual solutions and

Williamson and Maharidge’s records of unchanging poverty suggest that the

social action urged in the original image is no longer needed or was completely

ineffectual. Originally intended

as rhetorical tools aimed at rationalizing the reform and relief efforts of the

New Deal, the FSA photographs are reduced to talismans of a distant past in

these reimages. That past is

present in these images from the 1980s, suggesting that it cannot and should

not be forgotten. At the same

time, these rephotographs remove the uncertainty in these images of the past by

showing us their future.

Comments

From Dale Maharidge

Hi Andi,

Thank you for writing about our book! But I want to make two corrections.

One, the woman posted below Maggie Louise is her daughter, Parvin. Maggie committed suicide in the early 1970s.

Two, in the text, I deal deeply and greatly with the need for a social safety net like that of the New Deal. Far from implying that the New Deal is no longer needed, I argued that we were losing it at great risk, the peril of which is now painfully apparent in this economy.

You may want to check out our new book, Someplace Like America, which continues this argument. If you type that title into Facebook, you will get three sites, one for the book, the documentary, and a feature film. The book's site has a detailed explanation that furthers our argument about how we must care for Americans.

Dale Maharidge

author of And Their Children After Them

Reply to Comment

Hello Dale Maharidge,

Thank you for your comment and for pointing out the correct identity of the woman in the photograph below Maggie Louise. I appreciate the correction.

Also, I suspect we are in agreement about the need for a social safety net. My questions with respect to rephotography concern the ways in which these images may signify on multiple levels. For instance, does the rephotograph suggest the pervasive nature of poverty and, in turn, the failure of the New Deal? Are rephotographs capable of serving as a call to action or can they only imply that social action is either impossible or no longer needed?

Thanks, finally, for pointing me toward your new book. I look forward to reading it and to continuing to think through these questions.

Best,

Andi