Image Credit: Metropolis Magazine

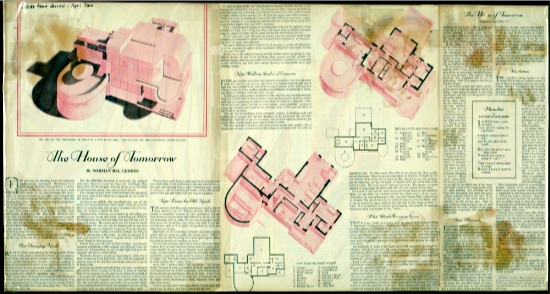

Walking through the Harry Ransom Center’s excellent Norman Bel Geddes exhibit, one thing that struck me is that while Bel Geddes is particularly famous for his large industrial designs—radios, cars, cities, and stadiums, for example—he also directed his talents towards the intimate spaces of the American home. Before Bel Geddes designed prefabricated homes for the Housing Corporation for America in 1939, or published his 1932 book Horizons, he wrote an article called “The House of Tomorrow” for the April 1931 issue of the Ladies Home Journal. The “twentieth-century style” he describes is one that he sees uniting form and function anew for the needs of the twentieth-century individual—or rather, what he imagines the twentieth-century individual to be.

Image Credit: Screenshot from Norman Bel Geddes's Horizons

Bel Geddes’ design philosophy is evident both within the article and in his manifesto Horizons, published the following year. As Bel Geddes and others saw himself principally as a set designer, he reframes his interest in industrial design as a kind of art for the modern era, where design has greater importance than ever before:

We are entering an era which, notably, shall be characterized by design in four specific phases: Design in social structure to insure the organization of people, work, wealth, leisure. Design in machines that shall improve working conditions by eliminating drudgery. Design in all objects of daily use that shall make them economical, durable, convenient, congenial to every one. Design in the arts, painting, sculpture, music, literature, and architecture, that shall inspire the new era. (4-5)

Bel Geddes here presents himself as an artist, who, like all others, “is sensitive to his environment” (6). He carefully notes the circumstances of life in 1930s America—post-industry, mid-Depression—and argues that they require new approaches to design in all these four phrases. He also works to break down the divisions between these different areas when he argues that “in the point of view of the artist who fails to see an aesthetic appeal in such objects of contemporary life as a railway train, a suspension bridge, a grain elevator, a dynamo, there is an inconsistency” (11). Bel Geddes argues that as modern life has centered increasingly around work, there is a greater need for conveniences, objects that function to promote ease and efficiency. Thus, while late nineteenth century art defined itself through Walter Pater’s formulation of “art for art’s sake,” Bel Geddes sees art in the perfect union of form and function

Visual design is concerned with form, space, color; with the proportioning of solids and voids and the rhythmic spacings of these elements. The governing factor as to what is pleasing to the eye is the idea, which is of an emotional nature—an emotion of pleasure, satisfaction, excitement, exhilaration, stimulation. (18)

What’s interesting here is how much emphasis Bel Geddes in this quotation places on the emotions of the artist. Elsewhere in Horizons, when he predicts that twentieth-century art will detach itself from galleries and statuary, he describes what he sees as the continuity between the art of the past and tomorrow: “The work of the artist always has been, and will be, a distinctly individual product—the antithesis of ‘machine-made.’ Fundamentally, the artist is an emotional person in that he relies more upon his feelings and intuitions than upon reasoning” (11). It’s easy to think that functional design must be based upon reasoning, but Bel Geddes flips the script to emphasize emotion, feeling, and intuition—language typically associated with the feminine.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

However, does publishing “The House of Tomorrow” in Ladies Home Journal necessarily imply that the twentieth-century figure he imagines is a feminine one? There could be a reading of the article that would point out the fact that the house is pink, that would consider the intertextual relationship between the drawings and discussion of design with the inset poem, “Hunches” by Elizabeth Boyd Borie, that would connect Bel Geddes’ intuitive designs with feminine thinking and feminine spaces. Yet such a reading might be incongruous with the Ladies Home Journal’s history, a magazine which published not only the muckraking work of Jane Addams but also Frank Lloyd Wright’s architectural designs. This widely-read magazine, like Bel Geddes himself, often contemplated questions of function, questions Bel Geddes emphasizes in “The House of Tomorrow.”

In fact, Bel Geddes quickly establishes the reasons he sees for a change in home planning and design: “The keynote of all the good contemporary work is that it must perfectly suit its ultimate purpose. We have returned to simplicity because we have realized in this age that the overornamentation and elaboration of the past are not in keeping with us today. We are more forthright people than were our forefathers, we bother less with forms and conventions, and so it is surely fitting that we carry our ideas into our homes.” This description of the modern American individual is one perhaps that sounds suited equally to our age as to the 1930s; he neatly transitions from thinking about the people to the houses that should shelter such folks.

Image Credit: Alcade / The Harry Ransom Center

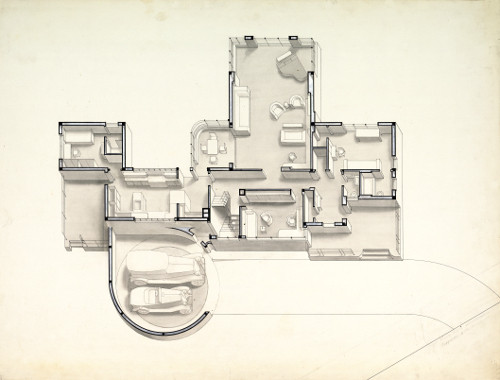

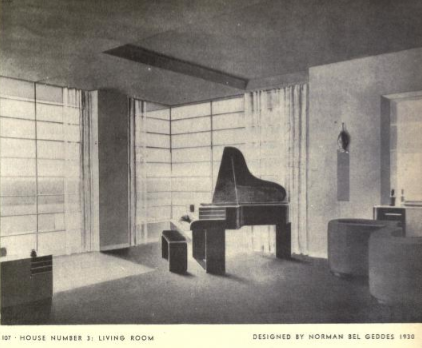

His solutions include moving the bedrooms from the front of the house to the back, nearer to the sunshine and expansive yards that are beautiful to behold. Even as he proposes to build more with steel girders and concrete, which might sound ugly, he notes that “in pursuit of light and air, since we are not bound down by any arbitrary limits, we can make our windows stretch the whole length of our rooms,” and likewise turn our roofs into flat spaces suitable for gardens. The emphasis he places on light, convenience, and the unity between interior and exterior design all bespeak his interest in making the home a place that does not trap its inhabitants but allows them “to take full advantage of all the innumerable aids to more convenient living that have been evolved in the past few years.” This emphasis on function is much in line with the kinds of rhetoric used in 1940s and 1950s advertising that encourages women to buy appliances to help with their domestic labor, but what’s refreshing is how ungendered his language is throughout the piece. If Bel Geddes expects the modern house “to assure complete satisfaction of every material and psychic need of the owner” (138-9), it seems that ownership is shared equally between the men and women in the space. Women have since the Victorian period been seen as the domestic goddesses, but Bel Geddes contemplates a twentieth century where their needs and interests extend beyond the interiors outward. Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, considering that Bel Geddes changed his name to include the “Bel” when he published his early writings alongside his first wife and collaborator Helen Belle Sneider, but Bel Geddes’s futurism offers new forms for old needs for women as well as men.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of viz. blog, and are not the product of the Harry Ransom Center.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago