Image:screenshot from volotov.com

“The first thing I want you to do,” Walt Disney is reported to have said to lead scriptwriter Larry Clemons upon giving him a copy of The Jungle Book, “is not read it.” Indeed. Not reading The Jungle Book, Rudyard Kipling’s 1894 collection of moral fables about Mowgli’s childhood among the animals and re-entry into human civilization, is a bit of a cottage industry. As one of the western world’s most famous feral children (alongside fellow turn-of-the-century literary peers Peter Pan and Tarzan), Mowgli has long been public property. But in the hundred-odd years since Mowgli, Baloo the Bear, and Shere Khan first entered our collective unconscious, the Jungle Books have embarked on their own odyssey that takes in everything from Imperialist allegory, Edwardian paramilitary organizations to Soviet science fiction and contemporary eco-criticism. And that’s just “The Bare Necessities.” All told, Mowgli’s adventures have taken him places Kipling—for all his fertile imagination—would never have dreamed, forming a kind of secret history of the twentieth century. In what follows, I try to quickly unpack some of that history through various images of Mowgli and The Jungle Book.

.png)

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Mowgli first saw the light of day in various short stories published throughout 1893 and early 1894, collected in volume form later that year. Only three of the seven stories concern Mowgli (“Mowgli’s Brothers,” “Kaa’s Hunting,” and “Tiger, Tiger”) while the remainder of the volume is filled with other animal tales— the proto-environmental narrative of “The White Seal,” and the classic tale of bravery and duty, “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi,” among others. Yet it was Mowgli’s ambivalent relationship to mankind, best expressed in “Tiger, Tiger,” as well as Kipling’s enunciation of “The Law of the Jungle” that caught early readers’ attention. With their portrayal of human society as deeply corrupt and their consequent valorization of Mowgli’s decision to “hunt alone,” the stories partake deeply of the degenerative cultural anxieties of their time (though oddly enough, Lockwood Kipling’s illustration above emphasizes Mowgli’s androgynous sexuality). Like all of Kipling’s imperial fictions, Mowgli works strangely—on the one hand, he clearly represents a kind of fetishized, animalistic native Other; but on the other, he surpasses human society. Closer to nature, he is also an idealized figure.

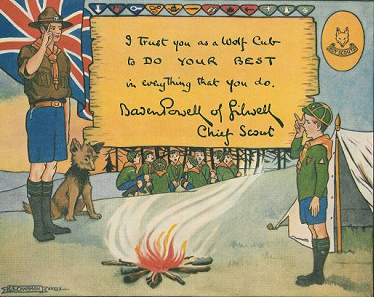

Image: http://www.scouting.milestones.btinternet.co.uk/cubs.htm

This was, of course, tailor-made for Robert Baden-Powell’s brief. Baden-Powell, alarmed by the early failures of the British military in the Boer War, famously founded the Boy Scouts as an attempt to reverse the degenerative tendencies of modern life. His foundational 1908 text Scouting for Boys had already incorporated the famous “memory game” from Kipling’s Kim; in 1916 Baden-Powell founded the Wolf Cubs as a junior arm of the Scouting organization. Its history, symbols, and motivations were drawn directly from, with Kipling’s approval, the Jungle Books. Even today the story “Mowgli’s Brothers,” now retitled “The Story of Akela and Mowgli,” appears in sections across the official Wolf and Bear Cub Scout Handbooks.

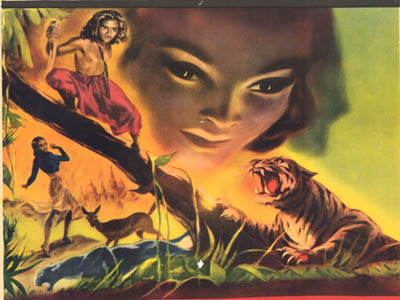

Further into the century, the Jungle Books were the subject of several major motion pictures, in particular Alexander Korda’s lavish, British Imperial spectacle from 1942 starring Sabu (whose film career particularly embodies the complexities of late colonial and post-colonial life for South Asians) and Disney’s famous 1967 version. The Korda version, made in the waning days of the British Empire in India to keep up morale on the home front, exemplifies the stirring, Orientalist fantasies the Korda brothers did so well--the film was a follow-up to the massive succes of The Thief of Baghdad (the poster for the 1942 film leads this post). As for the animated version, Walt Disney's quote makes clear that the text was merely a springboard for character development. That version would steamroll the ambiguities of Kipling’s tales into a narrative preparing young Mowgli for a productive life among human society (though at least it largely avoids the uncritical Orientalism of the 1994 live-action version, which also perversely failed to cast an actor of Indian descent in the lead role).

Image: www.realussr.com

More intriguing to me are a pair of Soviet adaptations of the work, the film-series Maugli [Adventures of Mowgli] (1967-71) and the science fiction novel Malysh [The Kid aka Space Mowgli] (1971). Maugli was released in five roughly twenty-minute sections, and, as the image above suggests, emphasizes heroic and epic themes. Unlike the Disney version, to which this series seems an ironic counterpart, the Soviet version remains fairly truthful to the stories. Apart from their emphasis on structuring masculine identity—an increasingly common theme in popular Soviet film and fiction during the post-Thaw years (and really, Kaa's positioning is none too subtle)–the Mowgli stories probably offered a veiled platform for discussion and critique of Western imperialism (the party line interpretation of French and American involvement in Vietnam). The full series is available here, though without subtitles.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, Arkadii and Boris Strugatskii’s Malysh uses the Mowgli myth as a distant political allegory. In the far future, the first colonists of a distant world use the Kid—the teenaged survivor of a previous attempt to explore the planet—as a proxy to briefly attempt communication with the indigenous closed society of “Ark Megaforms” discovered living on the planet. The story ends, however, with the failure of the Ark Megaforms and humanity to communicate. The colonists depart, leaving the Kid behind, with only a transmitter as his link to human society. Here the Mowgli myth structures a deeply moving allegory of failure to communicate, in which the West (or is it the East) remains unable to penetrate and speak with the closed society of the East (or, again, is it the West)? These transformations of the Mowgli story seem ripe for further examination.

Image: dailymail.co.uk

Finally, British graffiti artist and all-around provocateur Banksy used the characters of The Jungle Book for his contribution to Greenpeace’s “Save or Delete?” exhibition in 2001. The controversial image of the Disney incarnations of the characters hooded and lined up for execution makes a vivid argument about environmental change. At the same time, I find it fascinating that the images seem to be invoked in a “non-colonial” environment. While the use of the Disney characters could be read as an argument implicating Disney’s corporate policies in environmental change—though I wouldn’t necessarily pursue that argument—there doesn’t seem to be a consciousness of colonial and racialist policies underlying the image. Is Bansky blind to those tensions in this piece, or does it seem to indicate that Mowgli’s origin as a product of colonial fantasy is obscured to 21st century viewers? Whatever the case, the ecological underpinnings of Banksy’s image suggests the ways the Mowgli myth continues to impact audiences in new and provocative ways, some hundred years after his first appearance.

Comments

Great post. Do you have a

Great post. Do you have a reading of Kipling's original? I'd be curious to talk more about this.