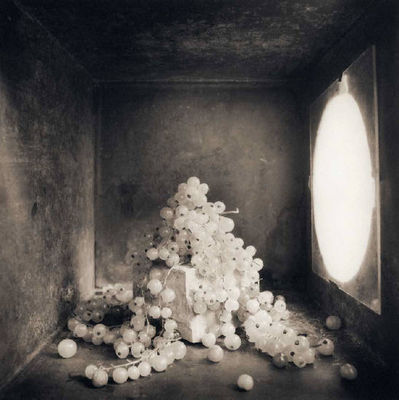

Image Credit: David Halliday on samuseum.org

Photographer David Halliday's current exhibition of still lifes at the San Antonio Museum of Art contains some stunningly beautiful and surreal photographs of food. It also lends itself to use in the rhetoric classroom and could be used for teaching lessons about visual literacy, changing contexts and visual rhetoric within communities. More about Halliday, still life and possible classroom uses after the break.

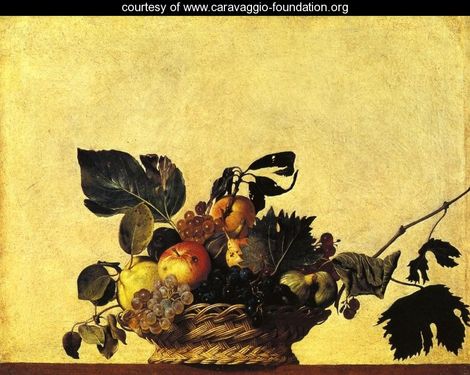

David Halliday is a New Orleans based photographer-turned-chef-turned-photographer. The photograph above is one of a series of still lifes produced in Italy using local ingredients and an old tin box. Halliday describes his "box" series, his own relationships to photography and food, and his current San Antonio exhibition in this interview on Zester Daily. In that interview, Halliday tells Liz Pearson that one direct inspiration for the series came from the Italian painter Caravaggio's still life paintings that were circulating on Italian currency when he was in the country. Halliday's subject matter (fish, vegetables, etc.) fall directly into the great tradition of European still life painting, and his use of lighting and his sepia-toned silver prints do a better job than most photographs of capturing the visual appeal of great Dutch or Italian still lifes. Many of the images make local ingredients appear like alien life-forms, like this de-familiarizing shot of a magnificent Italian cauliflower.

Image Credit: David Halliday on ZesterDaily.com

While these photographs are visually interesting devoid of context, they might provide a great way for rhetoric instructors to bring discussions of context and visual literacy into the classroom. Traditional still life paintings use fruits, vegetables, fish, pheasants and other types of

produce as a doubled system of signs. The natural bounty arranged on tables or in baskets stood as signs of wealth and bounty but also as memento mori. Life is good, they tell us and their original burgher viewers, but it doesn't last. The

arrangements are attractive and the subjects usually appetizing, but

the produce, unlike the painting, has a very short shelf-life. Having

been caught, picked or plucked, they will soon be rotting. Some still

life painters, including Caravaggio, even include signs of decay (wilting leaves, shriveling grapes, flies, etc.) to drive home the point.

While they obviously look back to those Early Modern paintings, Halliday's photographs show no signs of rotting, but they do evoke the freshness and

thereby the transience of their subjects. Rather than evoking a 17th century sense

of mortality, Halliday's focus lingers on the food itself, and in an era of refrigerators, chemical preservatives and grocery stores that stock the same products year round, really conceiving of our food as part

of a natural, seasonal cycle may be just as shocking as coming to terms with our

own mortality. The change in context--the difference between pre- and post-industrial worlds--accounts for the shifting target of the images. Caravaggio's viewers could use seasonal produce as a familiar object with which to contemplate the less familiar concept of their transient lives. For Halliday's viewers, the produce itself is unfamiliar and worthy of contemplation.

This type of contemplation is encouraged by several contemporary movements away

from processed preserved packaged foods and towards fresh, seasonal and

even local ingredients. The Halliday exhibition was put together in

part because the curator at the San Antonio Museum of Art wanted to connect the museum's mission with several changes in the local community including the opening of several new farmer's markets and a San Antonio campus of the Culinary Institute of America. Halliday's photographs dovetail with his personal

interest in his own vegetable garden

and the curator's interest in local farmer's markets: each moves food

out of the system of global distribution and economies of scale and

back into the cycle of seasons and cultivation where food is produce

and not an industrial product.

Halliday's photographs might not operate in the same registers as his

early-modern predecessors, but they do ultimately use images of food to

make us reflect on our own lives. Rather than reminding us that life is

short and we're going to die, his still life photographs remind us that our lives are part of a larger system and that the food that sustains our lives comes from the same ground to which we

will eventually return.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago