Image Credit: Markley Boyer/Wildlife Conservation Society

H/T to The New Yorker

Next month, I’ll be making a long-awaited trip to New York City, my adopted hometown. To prepare, I’ve been studying Adam Platt’s latest restaurant reviews, reciting Walt Whitman’s “Give Me the Splendid Silent Sun” nightly like prayer, and spending quality time with landscape ecologist Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta Project.

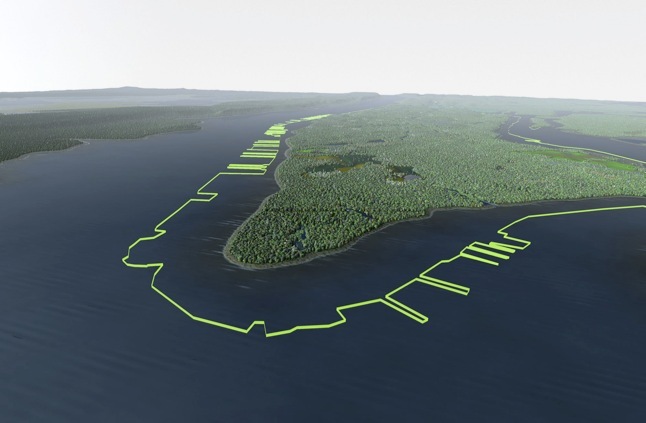

A digital map of the island as it appeared in 1609, when Hudson first sailed into New York Bay, this visualization tool offers an intriguing argument about the city’s ecological future.

The (cleverly named) Mannahatta Project slyly repurposes the technologies employed by Hollywood disaster flicks to recreate the island’s former biodiversity and to model the 55 different ecosystems the island once supported. The model also takes into account the activities of the Lenape, whose 5000 years of settlement and cultivation also impacted the island's ecology. Project Director Eric Sanderson's TED talk provides an accessible overview of the complex, decade-long process of spatial layering, “geo-referencing,” and spinning of Muir webs involved in trying to re-capture the island's remote ecological past.

Image Credit: Markley Boyer/Wildlife Conservation Society

H/T to The New Yorker

Sanderson insists that the project's goal is not to lament the loss of the 1609 Mannahatta but to see today's Manhattan anew, to come to understand the city as a habitat, with its own dense, resilient networks. Sponsored by the Wildlife Conservation Society at the Bronx Zoo, the Mannahatta Project is pitched as a tool that will allow us to design sustainable cities. I.e., by digitally reconstructing Manhattan Island as it might have been in 1609, the Mannahatta Project opens up a cognitive space for imagining what (else) New York might become. Sanderson’s visualization of Manhattan in 2409 shows rooftop gardens growing produce, city-dwellers on bikes, streams instead of sewers, and greater popular density to leave space for reclaimed green areas. No longer would one have to choose, as in Whitman's 1865 poem, between "Manhattan streets, with their powerful throbs...Manhattan crowds with their turbulent musical chorus" and Nature's "primal sanities."

Returning to the question Noel posed two months ago: does the Mannahatta Project work as a new, creative visualization of ecological crisis? Is the message too buried, indirect? Have we altered the landscape too drastically for an effective (and affective) recognition of Mannahatta in 1609 as our city? I think that the site's exploration tool succeeds in appealing to New Yorkers' fierce turf loyalty, allowing visitors to select a particular city block and access information about its former (and current) native wildlife. The project works to make these landscape alterations personal, intimate, but I'm curious if it has the same appeal for non-New Yorkers.

Image Credit: Markley Boyer/Wildlife Conservation Society

H/T to The New Yorker

P.S. Sanderson has also authored a shiny coffee-table book: Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago