Image Credit: Screenshot from NBC Olymics website

I’ve loved watching figure skating since I was a kid enjoying the movie The Cutting Edge. This meant that I used my free time last night watching the men’s figure skating short programs. My attention was drawn not only by free time, but also by the extensive press coverage given to the American figure skater Johnny Weir in the last month, especially related to his decision to wear fake fur to the Olympics after PETA threatened to protest him.

Weir’s position within the Olympics and within figure skating discourse is incredibly interesting. While he has a wide and vocal fanbase who enjoy his flashy costumes and artistry, much of the discussions surrounding Weir have to do with how Weir’s flamboyance is either good or bad for men’s skating. (Stephen Colbert, for example, alluded to Weir’s “crippling dependence on fabulousness.”) The commentary provided by Scott Hamilton and Sandra Bezic over his short program yesterday was fairly coded as they drew attention to his “pink tassel” and how “controversial” he is, but the controversy seems to only be whether or not Weir’s fey appearance makes men’s skating look gay—and thus, bad.

Image Credit: Screenshot from NBC Olympics website

The problem for men’s figure skating in general seem to be one of branding: while certain parts of the populace associate the sport with effeminacy and dismiss its claims to being a sport, the Team USA wants it to be taken seriously as an athletic competition. Magazines like Entertainment Weekly focus on the costumes, as did the New York Times in their discussion of the Swiss Stéphane Lambiel, who

either forgot to remove his vest before competing or wore something with shoulder pads that suggested Robin Hood joining the N.F.L. There was a Seinfeld puffy shirt thrown in for extra effect. One of the inhouse radio announcers thought he looked like Count Chocula.

In contrast, skaters like Weir defend their athleticism: “I like sparkly things. I like the theatre of figure skating. But in no way does that make me less macho than someone in a muscle shirt and tattoos with grease stains or whatever.” Aleksei Mishin, the coach for the defending gold medalist Yevgeny Plushenko, emphasizes the importance of the quadruple jump to the sport: “Skating without quads is a time before Stojko, before Urmanov. Who is not able to jump it, don’t make fake explanations. It is a shame to skate without quads.” His language of “shame” ties atheticism to manliness in skating: a manly good skater can do the physically demanding jumps, and an effeminate bad skater can’t.

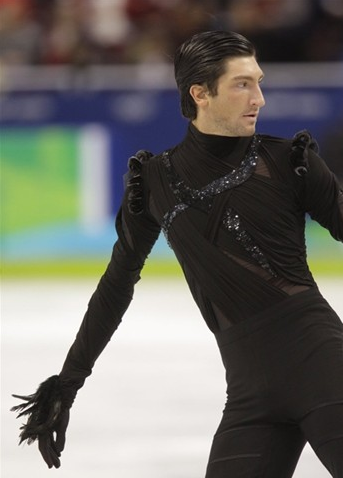

Image Credit: Screenshot from NBC Olymics website

The rivalry between Weir and his American teammate Evan Lysacek, where the former is considered “artistic” and the latter “athletic,” doubles this fight between figure skating’s claims to being a sport and its associations with homosexuality. Michelle Kwan in one video describes Evan as a “stud” and Johnny as “a cross between Adam Lambert and Lady Gaga” to reinforce Evan’s status as the Team USA champion and the medal threat and Johnny’s status as a less “serious” skater.

Image Credit: Screenshot from ESPN website

Yet Evan’s costumes last night were designed by Vera Wang, and the ESPN front page advertises “drama” by pairing the words with Lysacek’s sparkling, feathered image, insisting on the same effeminate connections that the skaters attempt to fight. Perhaps the problem isn’t Johnny Weir or any effeminancy on the part of the sport, but in the minds of individuals who can’t reconcile sport’s traditional homosociality with the masculinity they project onto such figures. This at least is the conclusion drawn by David Ross, former director of the Whitney Museum, in an interview on Olympic art with Stephen Colbert:

Analyzing the costumes of the men’s figure skaters and comparing the militarist look of Stéphane Lambiel with Johnny Weir’s pink tassel and Plushenko’s sequins might help students unpack binaries of masculine/feminine and straight/gay and consider how those definitions are culturally and rhetorically constructed.

Comments

American coding?

How much do you think the coding of male figure skating as gay is an American phenomenon? Do you have a sense of Russian, Swiss, German, Chinese (etc.) skaters being portrayed or perceived in similar ways at home? Since dance and theatre are both perceived as queer in the US, it would almost be more surprising if figure skating (which is an athetic performance more than a sport) weren't perceived in a similar fashion. (Is the American feminization of Europe--stretching all the way back to Crevcoeur--making an appearance?)

It also seems possible that the lack of a team exacerbates the tendency to remove skating from the realm of traditional, straight masculinity: gymnastics is a judged competition coded as feminine, but a gymnist has teammates clapping for him or giving him high-fives when he comes off the pommel horse. Unlike gymnastics, skating can't access the homosocial as an alternative to the homosexual.

Interesting point

Coye, I was actually thinking about this last night as I was reading the Oh No They Didn't Olympics thread; one of the individuals on the thread asked who the others thought might be gay--the conversation fell into a distinction between the straight Europeans and the gay Americans, and reminded me of the commonly asked question, "Gay or European?". I'm not familiar with how they're portrayed in their own media, and they figure differently in the American press too, because American skating has a different significance in America than other skaters.

As to gymnastics, I was actually referencing (as was Johnny Weir in his quotation) football, which is a sport in which men wear spandex, slap each other on the butt, but aren't perceived as homosexuals. But you may be onto something with the team dynamic--while Team USA might try to reassure each other, it is really every man for himself. But then, speed skaters are exempt--maybe it's in part the combination of a lack of a team with the emphasis on show that men's skating presents. This actually seems similar to the issues surrounding actors in musical theater, where some of them are not gay, but they are presumed so unless otherwise spoken.

Oscar Wilde on ice

Rachel,

I just found this snippet about Weir on his Wikipedia page: "Weir has consistently declined to answer questions about his sexuality. He stated: 'There are some things I keep sacred. My middle name. Who I sleep with. And what kind of hand moisturizer I use.'" Isn't that essentially the same thing as saying, "Yes, I'm gay"?

As for football, the players do wear stretchy pants, but the pants are part of a UNIFORM not a COSTUME, and I think that makes a big difference. The uniform-- even the uniformity-- is part and parcel of the homosocial atmosphere that keeps tight pants and butt-slapping from being coded as homosexual.

I am more interested in how a competition's evaluative criteria (clock or points vs judging) affects how an athletic event is coded. Lugers and downhill skiers where spandex and don't have team members, but their sports are clock-governed and (as far as I can tell) never coded as homosexual. Do we, in America, see something in subjective evaluation that makes us think "gay," or is it just the music and the fur trimming?