Credit for Eedited Image of Leo Tolstoy: Sean Ludwig

Educators and everyday people alike have spent (at least) the last half of a decade in a state of ever-increasing turgidity as they speculate as to all of the amazing feats the e-reader (usually, “e-reader” means “iPad” in the popular discourse, so I might use both terms below) will achieve in the context of public education. It is almost assumed that replacing every student’s bulky, quickly-dated paper textbooks with sleek, capability-rich e-readers is an unequivocally good, nay, downright imperative educational initiative.

However...

...I (generally) hate to poop on parades, and I’d agree that there’s nothing wrong with high hopes, but it would appear as though the e-reader, culminating in the iPad, has reached the point where expectations regarding a new technology have become so enormous in both quantity and scope, that there is no possible way they could all be met.

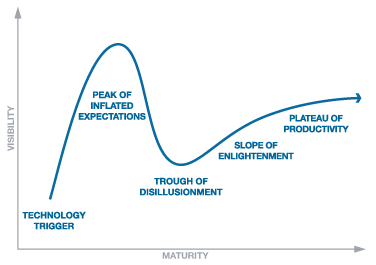

Image Credit: Gartner's Hype Cycle Research Methodology

One way to illustrate what I mean is to turn to Gartner’s somewhat-famous Hype Cycle, an illustration of which is above, this point is an inevitable stage in the life of any truly groundbreaking technology. If we were to endeavor to locate the collective attitude of educators towards e-readers at the moment in the terms that Gartner coined in conjunction with their cycle, I’d speculate that we've arrived at the Peak of Inflated Expectations. (As an aside, I realize that the above illustration is one of a curve, rather than a cycle. But, Gartner calls it a cycle, so I guess we will, too!)

If this is the case, maybe it’s time for the discourse to return to the reasonable, which would mean that we would have to at least entertain the possibility there might be trade-offs to all of the touted advantages of moving textbooks, etc. to a digital format. At the moment, even when problems regarding moving from codex to e-reader are mentioned, the issues that are raised tend to be relatively immediate- rather than long-term- in nature. Raising larger questions regarding the practical, legal, or- God forbid- philosophical pitfalls usually elicits nothing more than a few eye rolls and dismissive comments about paranoid delusions.

Maybe these rollers-of-eyes have it right. I'll be the first to concede that I am more reluctant to trust the powers-that-be than any rational person ought to be. Still, shouldn’t we at least acknowledge that a provider of school reading materials that has the absolute logistical power to provide information would also have the absolute logistical power to withhold or even take back information from a purchaser?

In a well-known example from a few years ago that isn’t specific to the educational context, Amazon removed a book from the kindle of every individual who had purchased it, without the buyer’s knowledge, much less consent. In an instance of irony that would be funny if it wasn’t so scary, the book reclaimed by Amazon was none other than the dystopian classic “1984.” As most already know, the book is about an all-pervasive government that is able to maintain its stranglehold on society because it- and only it- has the power to provide, withhold and rewrite the official history it propagates if it decides that it’s advantageous to do so.

This example is also frighteningly ironic to the extent that “1984” is a book that has been part of public school curricula since it’s publication, despite countless attempts to keep the book off of school syllabi. In other words, Amazon was able to take away reader’s access to material with the click of a button in a way that decades of organized protest movements could never achieve. But the scariest part of Amazon’s taking was the absence of backlash from the public. The story quickly fell outside of our collective attention span; their out-of-court settlements amounted to little more than a slap on the wrist.

Why was this the case?

I don’t think the absence of public outcry regarding this sort of thing is indicative of an indifferent public. Rather, by the very nature of the digital medium, censorship and control over access to literature and other texts can be performed in a way that is more or less invisible and instantaneous.

If its degree of threat lay in its degree of insidiousness, however, the threat of having books taken off of our virtual shelves isn’t nearly as great as the threat of having the content of a books being subtly censored/altered.

Consider last year's quickly-fleeting story wherein a careful reader found that the copy of Leo Tolstoy's "War and Peace" he had received as a gift for his Nook (Barne's and Nobel's e-reader) had been modified from the original text throughout, with instances of the word "Kindle" word having been replaced with "Nook," a brand name belonging to the company who had contracted with the e-book's publisher. Why did one of the world's largest booksellers think that it was "Ok" to secretly alter one of the pinnacles of world literature in the interest of increasing market share? Could anyone honestly have thought that no reader for the of time would ever notice a change in Tolstory's prose that produced sentences such as, "It was as if a light had been Nookd in a carved and painted lantern," and "Nook in all hearts the flame of virture?" I doubt it. But they did it anyway, operating under the belief that nobody would really do anything about it when the changes were noticed. Given the almost total absence of public outcry over the incident, it would appear as though they were correct.

If the electronic medium allowed for the “cover-to-cover” alteration of one of the most revered and frequently studied literary works of all time to go undetected (and, to my knowledge, unpunished), it’s hard to exaggerate the ease with which subtle changes could be made on a few pages in one chapter in one standardized textbook among the thousands of standardized textbooks presently in use. More troubling, it's hard to exaggerate the collective apathy such changes would be met with, if recent history is any indication. Maybe we need to bring issues considering the control, dissemination, and alteration of the books we bring into the classroom (and anywhere else, for that mater), even if doing so will burst many of our bubbles about e-readers and the like...even if that sends us into Gartner's Trough of Disillusionment. I'll take disillusionment over misinformation any day of the week.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago