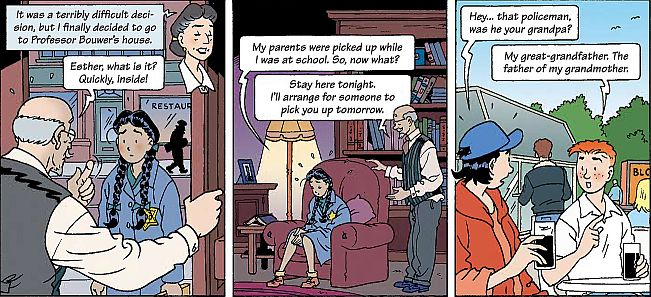

Many of you may have seen the story in the New York Times yesterday about a comic that has been introduced in Germany to teach students about the Holocaust. (A brief portion from an English translation appears below.) This week, 25 Feb. through 2 Mar., is actually Holocaust Awareness Week, so some attention is being paid to issues surrounding the teaching of the Holocaust in this and other countries. More examples, after the jump.

The article notes that

With the Second World War passing from living memory, the Holocaust remains a subject taught as a singular event and obligation [in Germany], and Germans still seem to grapple almost eagerly with their own historic guilt and shame. That said, few German schoolchildren today can go home to ask their grandparents, much less their parents, what they did while Hitler was around. The end of the war is now as distant from them in time as the end of the First World War was from the Reagan presidency. Paradoxically, this seems to have freed young Germans — adolescent ones, anyway — to talk more openly and in new ways about Nazis and the Holocaust. Passing is the shock therapy, with its films of piled corpses, that earlier generations of schoolchildren had to endure.

This discussion sets up an interesting contrast between the "shock therapy" of the past and the comic book, called "The Search," "The visual style of [which] is clear, simple, pastel-colored, in a classic Belgian-Franco comic tradition. 'Less is more,' Mr. Heuvel, the artist, said in a recent telephone conversation..." Mr. Heuvel points to the creator of Tintin as one of his influences.

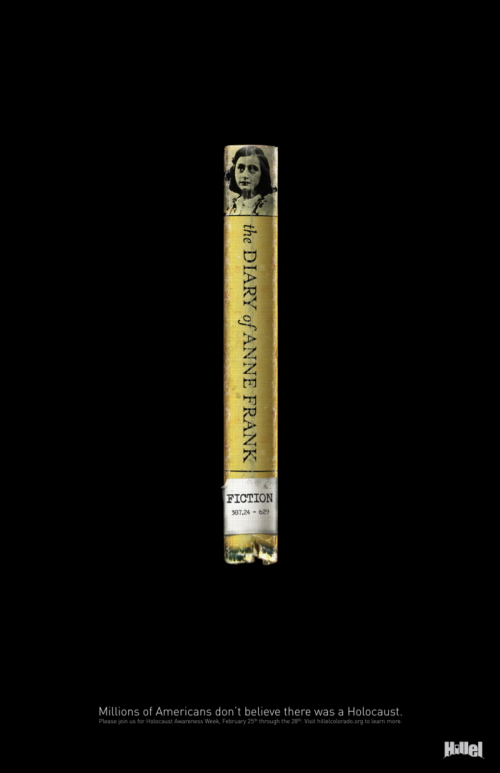

This less is more philosophy is also at work in this poster, created for Hillel Colorado:

According to one blogger, Angela Natividad at AdRants, "This is one of those well-tempered print ads that forces you to really look before you know what's going on. Most people will probably miss the point while rushing by on the subway, but those that catch it might go, 'Hrm' and bring it up in random bar conversation." The kicker of this stark, spare, but effective image is the Fiction label attached to the book's spine.

Natividad contrasts the effective simplicity of this image with the more forceful, less subtles visual style of the following two spots, created for Think MTV (Until yesterday I had never heard of it, but according to its homepage "Think is your community where you, your friends, and your favorite celebrities can get informed, get heard and take action on the issues that matter to you most."):

In their different ways, each seems like an effective approach, although the contrast between the visual styles of the comic book and the video spots is somewhat stark. (However, the Times article also quotes one source who says that using black and white imagery to depict the Holocaust has become a cliche; each of the spots ends with an actual black and white image of Holocaust victims.)

In the Times article, one of the teachers using the German comic is quoted as saying that the comic "teaches the subject...so it's not just about victims and perpetrators," and that "the result [of teaching the comic] is that interest in the subject is actually increasing. These students don't have the same discomfort we did talking about it" (emphasis added). I want to call attention to two assumptions made here: one is the emphasis on the Holocaust as a "subject," and the other is his point that students don't have as much "discomfort" when they talk about the Holocaust. I don't mean to suggest that modern, teenage Germans especially should feel discomfort about the Holocaust--but, in fact, shouldn't everyone, regardless of nationality, feel some discomfort when talking about this "subject"?

Comments

When The New York Times

When The New York Times writes, "Passing is the shock therapy, with its films of piled corpses, that earlier generations of schoolchildren had to endure," do you think they are suggesting that these films of corpses (e.g. Shoah) no longer have a place - so a kind of either/or approach to visually depicting what happened? Or do you read this as more of a both/and approach to representation?

Related to my previous comment, I must admit that I found the Think MTV ads compelling (does that mean I am the target audience for the Think MTV community? I hope not!). I like how they segue from contemporary spaces and places to images of past violence. However, I imagine that the MTV ads work from an older understanding of how to represent these atrocities, and contrasts the "new" and "open" ways that the NYTimes article discusses.

That's a good question. The

That's a good question. The article leads me to believe that the newer approach is supplanting the old one. For example, one of the writers of the comic book is quoted as saying,

But perhaps it's a matter of age difference: the comic may be for younger students, and other materials may be used in classrooms for older students.

I also like the MTV ads, particularly the subway one. There is something effective about the connection between these quotidian experiences and the Holocaust that is effective. But I'm not sure what response they would engender beyond a certain "Whoa..." At the Holocaust Memorial and Museum in Dallas, which I visited a couple of times while I was in high school, there is a box car that is believed to have been used to transport people to concentration camps. While being led through the museum, you are actually taken inside it, where you are asked to pause and (if I remember correctly) observe a moment of silence. That, I thought, was extremely discomforting, but also extremely effective.

This, of course, makes me

This, of course, makes me think of Art Spiegelman's Maus, a memoir of his father's survival that is not only written in comic book form, but also represents the characters as anthropomorphized rats, pigs, etc. I read it for a class (a notably popular class) called Representing the Holocaust, and the reasons that drew people to the book (form (low art), narrative (nested and self-reflective), characters(displacement through animals)) were also the points of discomfort with the critics. I can't say I loved the book, because an effective chronicle of trauma is itself traumatizing, but what I did appreciate about the text was its difficulty, how despite being presented as a comic, it resisted reducing the "subject" to something that can be altogether accessible. And this is perhaps what bothers me with the project at hand, and as you pointed out, its isolation of the "subject" from perpetrators and victims. Something that I like about the MTV campaign is that you are indicted (albeit only along the lines of the victims) in the "like us" and not encouraged to see the Holocaust as a "subject" out there or something altogether foreign or external. I think the ads could go further, though, and remark that the Holocaust not only happened to people "like us" but was also supported by people "like us." This would more effectively communicate (albeit in perhaps a less benevolent manner) that note about perpetrator and hero.

Unspeakable truths

Yes, at least in this country, Maus is a reference point. What's interesting about the comic described in this post, however, is that it is rather stylistically old-fashioned. Maus has been hailed as one of the great innovations in the genre in marking the move from "comic" to "graphic novel." In opting for a lighter (both literally and figuratively) approach, the creators of this comic made an interesting choice. In this case, form and function are definitely related, as the discussion of the transition to "subject" may indicate. The artistic choices reflect the philosophical approach to the treatment of content--in a way that I regard as kind of strange considering the direction in which most comic artists/illustrators/graphic novels have moved over the last 20 years or so.

And your point about the MTV spots is dead on. In ignoring the fact that the perpetrators were also just like us, the creators of those ads miss what is probably the central point about the Holocaust that should be emphasized. But that fact--the possibility that we could be anything like them (which is, incidentally, a central argument of Giorgio Agamben's)--is something of an unspeakable truth, no?

speaking the unspoken

Your last comment reminds me of the controversy (and praise) surrounding Daniel Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust. Here is an excerpt from his book that looks at this questions of the perpetrator:

You can read more here