Image credit: Wikipedia

I'll test my art history chops today (no promises) as I explore the work of Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1527-1593), late Renaissance Mannerist and an artist of interest to everyone from the critic Barthes to the stadium rock band Kansas to the surrealist Salvador Dali.

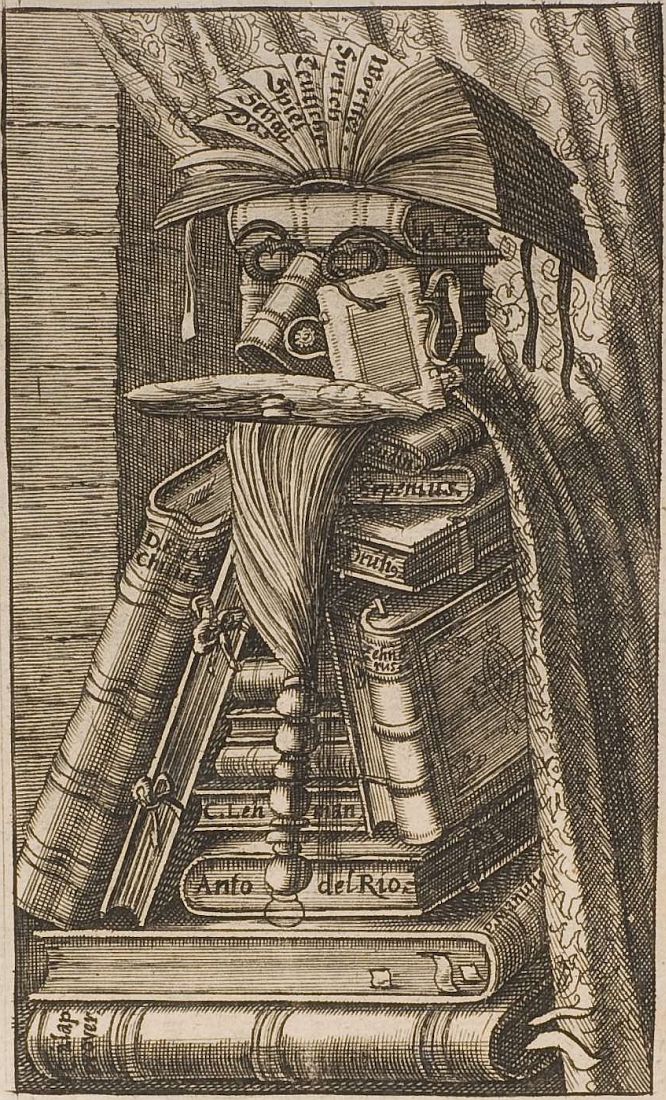

The designer(s) of this year’s TILTS symposium flier chose an engraving after Arcimboldo’s The Librarian (1566). In investigating some context for the painting, I couldn’t help but notice the aptness of the image—not only, of course, because of TILTS’ ever-present commitment to textual studies, but because of the particular place Arcimboldo holds in literary and popular imagination in the Post-Renaissance world.

Image Credit: Wikipedia

“Fate” is a tricky word because it, in its very definition, denies agency. In its most general sense, it is neutral; in its most particular, it signifies destruction and certain doom. Fate implies an unarticulated threat, inalterable and unavoidable, existing always in negation of the object at hand. In its most classical sense, the hubris to resist it can propel fate, giving it wings, enabling it in its most monstrous form.

And so here we are, two years after TILTS’ “The Digital and the Human(ities)” Symposium (2010-2011), approaching the issue of the digitizing of text from a different perspective. While in broad strokes, TILTS explored the possibilities of the digital in 2010, in 2012, it seems to be exploring, at least in part, the anxieties surrounding this structural shift—anxieties which, as the title so aptly captures, center around “the book’s inevitable ‘death’.” How can we read Arcimboldo’s imagine in tandem with this approach to the discourse of the digital humanities?

To begin, we might read Arcimboldo as existing in a pivotal (fated?) moment, as well. Painting after the last greats of the High Renaissance but at the cusp of the Baroque, he reaches back to High Renaissance aesthetics in the composition of his paintings in his form of composition, even as the work contrasts Michelangelo and Raphael in his content. But Arcimboldo’s composition strives to integrate man with nature and to highlight the divine in the marriage of the two—a distinct shift from the Neoplatonism of the High Renaissance, which elevated man as the near-divine and instructed that art should seek inspiration from the aestheticized universals (“Forms” or “nature”).

Arcimboldo’s clever visual articulation of the intersection of man and nature attracted the attention of Roland Barthes in his Arcimboldo essays; Barthes fixates on the way the artist employs rhetorical tropes into his painting—metonymy and paradox, for instance. For Barthes, Arcimboldo is a “rhetorician and magician” because of the structural semiotics he represents in his paintings; each part of what we recognize as a face is a discrete element meaningless in isolate, but when assembled, the elements of his paintings produce meaning in a sum greater than their parts. While Barthes argues that these “puzzles” are a metaphor for language, they also strongly exhibit Arcimboldo’s debt to Florentine Neoplatonism in their commitment to displaying meaning only as a composite body. When dissected, they cease to speak.

Scholars read “The Librarian” in two distinct ways. The contemporary reading (which much subsequent scholarship has acknowledged or substantiated) argues the portrait was a personal attack levied at one Wolfgang Lazius, HRE Ferdinand I’s court historian in the Habsburg court at Vienna, for his vain and inaccurate scholarship. Yet K. C. Elhard argues instead that Arcimboldo’s painting criticized not poor scholarship but poor bookmanship—that is, it levied a critique against “materialist book collectors more interested in acquiring books than reading them.”

Interestingly, as many scholars of present-day book history have noted, this is exactly the type of behavior that publishers in a dying book market attempt to capitalize on today. The one thing digital books cannot provide is the pleasure of owning a material object; as the symposium’s blurb asserts, “any publishers in the print trade are turning to eye-catching design strategies, cover art, and innovative packaging, enlivening the book arts and emphasizing physicality just when they seem under threat.” Tonight’s opening lecture (5:30 pm in the Blanton Auditorium) by Nicholson Baker, “staunch defender of paper objects,” is sure to expand the discussion of materiality of text to further interesting places. Perhaps someone more creative than I wants to update Arcimboldo's painting for the digital age?

Image Credit: LT

A closing word on our Painter/Rhetorician/Magician: perhaps existing between two major movements of European art, fitting neatly into neither, sealed more than anything else Arcimboldo’s fate in the canon of the Early modern. Though he has received no small amount of attention, in comparison to the great Renaissance and Baroque painters he remains ever the side show: a curiosity and a puzzle, but one that keeps me interested for more than just a game or two.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago