Rachel’s post this past week about the low-fi appeal of

recent music videos raises similar questions to those surrounding a recent

controversy over a digitally altered image stripped of its status as a World

Press Photo contest winner. And,

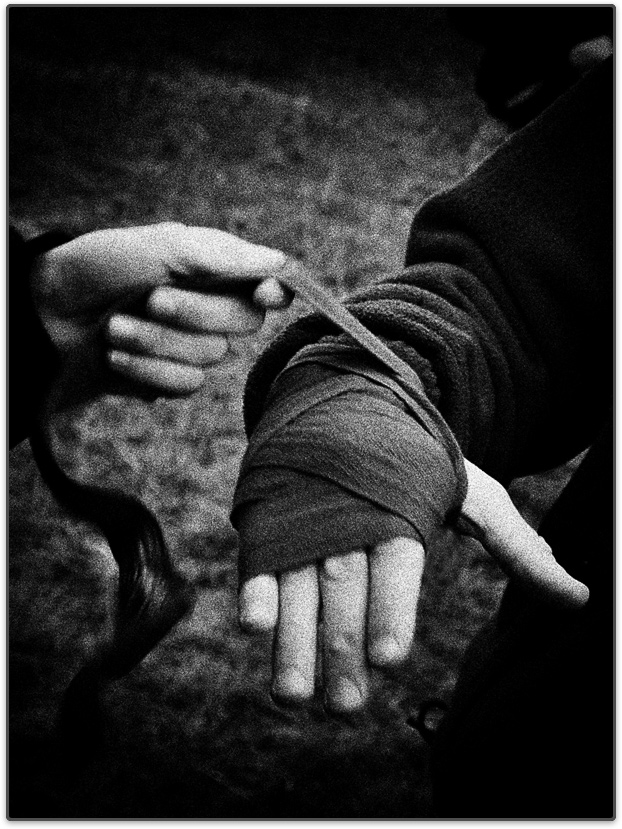

what was the alteration that led to this disqualification? Third prize winner in Sports Features, Stepan Rudik removed a foot from the finished photograph. World Press Photo, an organization

known for promoting professional standards in photojournalism largely through the

means of awarding one of the most prestigious photography prizes, disqualified

Rudik because the jury discovered that he had digitally altered one of the

images in his photo-essay submission. Both the low-fi aesthetics of the OKGO

video and the field of professional photojournalism privilege a definition of

technical prowess that does not include manipulation of the image beyond much

capturing and cropping. The value

of the image and the skill of the image-makers, in both of these respects,

reside in the moment the photograph is shot and not at any other point in the

process in which the photograph is made.

It is interesting that World Press Photo takes such pains to

distance itself from the artisanal aspects of making a photograph and falls

back on a presumption of authenticity aligned with the decisive moment. So, good photojournalism is not made

but captured? Are these prizes

just awarded to extremely lucky individuals? For the award committee, there seems to have been an

implicit emphasis on aesthetically stunning images combined with an explicit

emphasis on photographs captured at that lucky pivotal moment. And, always, the assertion that nothing

has been altered. Amazing

technical prowess at the moment of capturing combined with low-fi levels of

retouching at the moment of making the photograph. Consider several of these past prize winners:

Image Credit: Jean-Marc Bouju

World Press Photo of the Year, 2003

Image Credit: Anthony Suau

World Press Photo of the Year, 1987

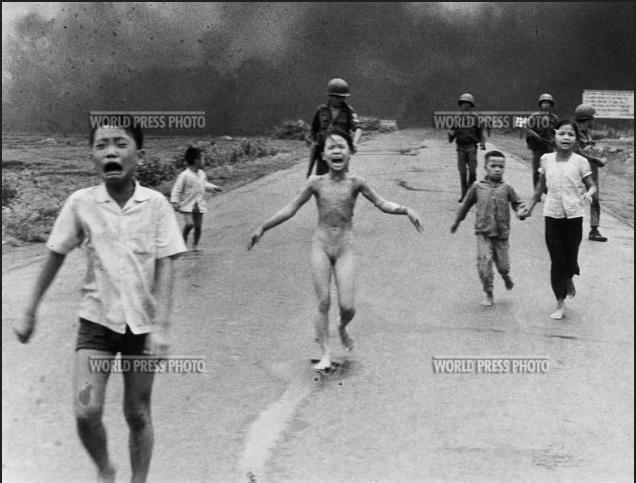

Image Credit: Nick Ut

World Press Photo of the Year, 1972

Although many of the prizes are given for images that are

aesthetically beautiful, the truth-claim of those photographs deemed excellent

photojournalism lies in the assertion that they have not been altered. World Press Photo’s rule reads, “the

content of the image must not be altered.

Only retouching which conforms to the currently accepted standards in

the industry is allowed” (Worldpressphoto.org). Perhaps this assertion is not all that surprising—after all,

it may be quite the slippery slope that runs from the removal of a foot to the

faking of photographs of missile tests.

But, where is the exact difference between altering aesthetics and

manipulating content? Is it okay

to punch up the grain of the image or switch from color to

black-and-white? Is it wrong to

crop out relevant context or wipe out a misplaced foot? What is the exact difference, in terms

of truth claims, between framing, cropping, and photo-shopping?

Comments

Interesting question!

This almost seems to link to journalism's polite fiction of objectivity: what goes into a newspaper and how it's discussed isn't entirely transparent, but not everybody thinks about that or believes that to be the case. (At least, that's how my 306 students always seemed to approach newspapers.) When one eliminates that claim of objectivity, some people will jump to thinking then if newspapers have "opinions" that they are biased and can't be trusted. The same seems to be going on here: if it's been retouched or edited, it's not "real". It seems like the reasonable response in both cases is to acknowledge that it's always blurrier than that. (For example, can you change the color balance of the photo? Raising the saturation to compensate for awkward lighting shouldn't be OK under this standard, it seems.) The problem with the slippery slope argument here seems to be that everything can become a slippery slope when most reasonable people would be able to agree on the limits.