By Rachel Schneider

One of the five major canons, delivery has often occupied an

instable place in rhetoric. Aristotle

dismissed delivery as being relatively unimportant to rhetoric, and with the

exception of the eighteenth-century elocutionary movement, delivery has been

readily ignored or imagined to be a subject for communications professors. Within the contemporary rhetoric classroom,

where most of the work examined is written communication, delivery remains

outside of the purview of most discussions.

However, as visual rhetoric often involves video as frequently as it

does static images, delivery may become a more important factor in rhetorical

pedagogy—not as we teach students to deliver speeches, but as we teach them to

analyze texts that are audiovisual.

One of the five major canons, delivery has often occupied an

instable place in rhetoric. Aristotle

dismissed delivery as being relatively unimportant to rhetoric, and with the

exception of the eighteenth-century elocutionary movement, delivery has been

readily ignored or imagined to be a subject for communications professors. Within the contemporary rhetoric classroom,

where most of the work examined is written communication, delivery remains

outside of the purview of most discussions.

However, as visual rhetoric often involves video as frequently as it

does static images, delivery may become a more important factor in rhetorical

pedagogy—not as we teach students to deliver speeches, but as we teach them to

analyze texts that are audiovisual.

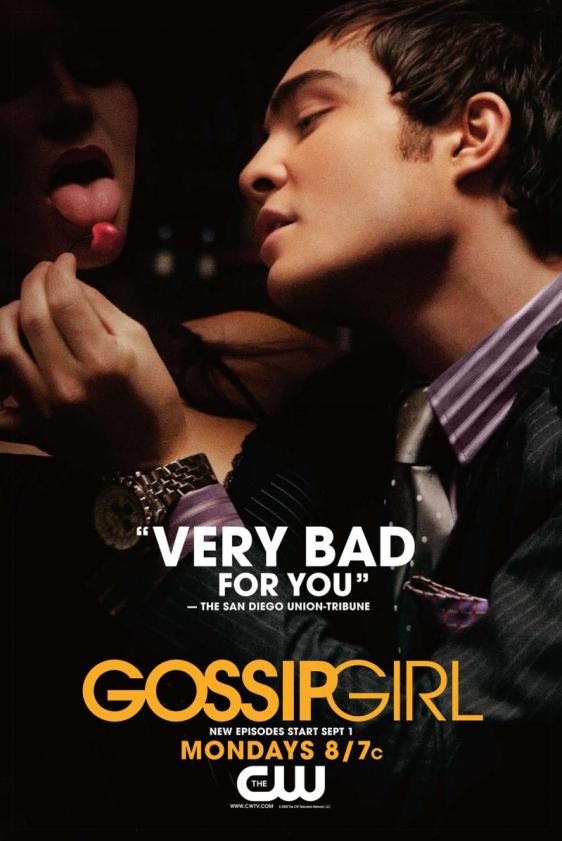

What makes this more complicated is that these audiovisual

texts are often not speeches—they are performed texts. A class on the rhetoric of luxury might as

easily focus on an episode of Gossip Girl

as it might an ad for Aston Martin cars; thus, a vocabulary of delivery needs

to learn to take into account performance not just in Burke’s or Austin’s

terms, but to think about how an actor’s performance attempts to convey

arguments through establishing sympathetic characters. This requires more than a language of

pronunciation, volume, and gesture, but rethinking how we analyze performances

as rhetorical texts. Teaching students

to read these texts, and giving them a vocabulary for articulating what they

find there, will help them learn to think critically about all forms of popular

media that they might encounter.

However, trying to teach students to think about analyzing

delivery in performed material involves a wide range of material. Just as Margaret Syverson encourages teachers

to think of composition as consisting of an ecology or “a set of interrelated

and interdependent complex systems” (3), so performance itself evolves as part

of a set of systems—actors working together, performing on a stage as they are

watched by an audience who participate in the performance through applause or

boos, all of which takes place within a larger theater. Just as the writer’s labor does not take

place in isolation, performance is dependent upon location, time, the

director’s guidance, and a host of larger contexts that have to be

considered. While we might look backward

to the elocutionists for a terminology, modern communications studies and

performance studies also offer help in thinking of ways to revive delivery for

the modern rhetoric classroom.

In his book on performance theory, Richard Schechner

stresses the need to study each performance on a case by case basis: “[A]s embodied practices each and every

performance is specific and different from every other. The differences enact the conventions and

traditions of a genre, the personal choices made by the performers, various

cultural patterns, historical circumstances, and the particularities of

reception” (29). In my own class, The

Rhetoric of the Musical, we’ve spent the semester considering how the musical

(a highly stylized genre) creates and frequently violates its own conventions,

how it balances the demands of believability and naturalness that is the

greater concern of twentieth-century acting with its own unnatural convention

of people breaking out into song at emotional moments. However, Schechner’s observation is perfectly

suited to rhetorical terms: each

rhetorical performance is already examined within its own particular context,

and the rooted concerns of speaker, audience, and text. Just so any analysis of a performative text

requires a sensitivity to the intent of gestures and vocal performance, and how

each are calculated to construct characters that attempt to engage the

audience’s sympathies to persuade them not only to watch the musical, but also

to engage on their side in the controversies of the plot. Bruce Kirle’s article on “Reconciliation,

Resolution, and the Political Role of Oklahoma! in American Consciousness” excellently

studies Joseph Buloff’s performance in the original 1943 Broadway production,

and how he signals a Jewishness that is acceptable to audiences, and thus

reconciles them to World War II interventionist military policies. His work shows the potential benefits for

thinking about delivery.

While elsewhere on this site I provide my own lesson plans

as a guide, I want here to include a list of materials that I’ve consulted in

creating a language of delivery for my students, as well as modern rhetorical

books that think about the place of delivery in the rhetorical canon. I hope this material might be helpful for

thinking about potential applications and ways to adapt delivery into the

modern rhetorical classroom as a method for analysis.

Works Cited and Related Sources

Buchanan, Lindal. Regendering

Delivery: The Fifth Canon and Antebellum

Women Rhetors. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Golden, James L., Goodwin F. Berquist, William E. Coleman,

and J. Michael Sproule. The Rhetoric of Western Thought: From the Mediterranean World to the Global

Setting. Eighth edition. Dubuque,

IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 2003.

Kirle, Bruce.

“Reconciliation, Resolution, and the Political Role of Oklahoma! in American Consciousness.” Theatre

Journal 55 (2003): 251-274.

McCutcheon, Randall, James Schaffer, and Joseph R.

Wycoff. Communication Applications. Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook Company, 2001.

Schechner, Richard. Performance Theory. Second edition. New

York:

Routledge, 2003.

Stucky, Nathan and Cynthia Wimmer, eds. Teaching

Performance Studies. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University

Press, 2002.

Syverson, Margaret A.

The Wealth of Reality: An Ecology

of Composition. Carbondale,

IL:

Southern Illinois

University Press, 1999.

Wolf, Laurie and Counsell, Colin. Performance

Analysis: An Introductory Coursebook.

Hoboken: Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2001.

Wolf, Stacy. “In Defense of Pleasure: Musical Theatre History in the Liberal Arts

[A Manifesto].” Theatre Topics 17.1 (2007):

51-60.

Wolf, Stacy. Handouts from TD357T “American Musical

Theatre History” Spring 2008 at the University

of Texas at Austin.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago