Image of Ron Mueck's In Bed (2005); Image Credit: Brooklyn Museum

Ron Mueck is an Australian sculptor of the "hyperrealist" school. He got his start working for Jim Henson and on Labyrinth (1986). Mueck became known to the art world for his 1996 Dead Dad, a two-thirds life-size sculpture of the artist's father moments after passing away. Mueck's sculpture attempts to reproduce human beings in all of their external reality. That is to say, while there are no organs on the inside, so far as what everyone but surgeons can see of a person, Mueck depicts, down to the last follicle.

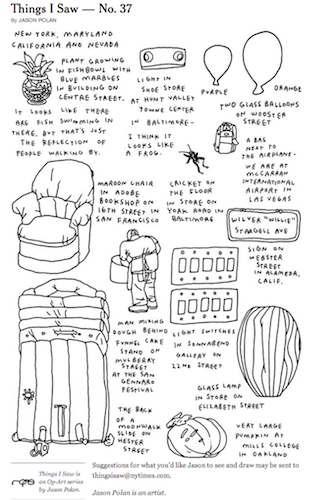

Jason Polan publishes a weekly series for opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com called "Things I Saw." Simple drawings with factual captions, Polan attempts to capture the quotidian.

Image Credit: Jason Polan

If Mueck captures the lightest freckle, Polan depicts the light switch on the wall. Though the visuals of these arts are strikingly different, their philosophies are really two sides of the same coin.

Getting at reality's details, significant because they are available to perception, has been realism's concern ever since it gave up explaining why things are the way they are. This was, at any rate, the great literary thinker György Lukács's explanation for how a relatively minor writer like Émile Zola could attain literary predominance over Walter Scott.

Reality offers so much to see: rather than try to fit it all into an understanding, the new realists have tried to depict it in the first place. They are anti-reductionists, Polan no less than Mueck. Clearly Polan's drawings don't depict in photorealistic detail as do Mueck's sculptures. But Polan's approach is the "wide" and "random" to Mueck's "close" and "complete:" both are premised on the fecundity of what is available to be seen. Polan gets at a greater sense of the available by looking broadly and by depicting what we usually do not think of as being worthy of depiction. The broken comb on the sidewalk is there, we know it is there, but we don't always give its there-ness due credit: thus Polan's anti-reductionism. Mueck gets at a greater sense of the available by looking closely and by depicting everything that is available to be seen without a microscope. The birthmark on the right butt-cheek is there, we know it is there, but we don't always give its there-ness due credit: thus Mueck's anti-reductionism.

The question is to what degree the details for each artist are superflous. Mueck, like Freud and E.M. Forster, is a technician in the art of slow-motion capture. If we could provide a sustained attention to what is only briefly but really there to be perceived, we would learn that every passing moment is suffused with meaningfulness. Conrad and Henry James worked in this tradition as well. In Walter Scott's novels, no detail is really superflous because he organizes them into an interpretative framework. He looks from the moon's perspective, as it were: he sees long stretches of time from a distance. For the psychorealists, like Mueck, a detail only seems superfluous because we do not consider it for long enough to understand its significance. That something may be perceived is reason enough for its significance, so finely attuned to reality is our embodied consciousness. Forster shows this by slowing things down in time; Mueck does it by either blowing things up, in scale, or shrinking them down, making the viewer lean in to find out.

Image of Mueck's Boy (1999); Image Credit: Yale Books

Image of Mueck at work on Spooning Couple (2005); Image Credit: Brooklyn Museum

Polan's panoramic view insists more upon non-significant randomness, which is also why he depicts non-human subjects, like the cricket or the lamp. I find Mueck's work more compelling, no doubt because his medium is so much more engaging, but also because he shows us something there and significant that we are able to interpret but not always given a chance to. In other words, his work allows us to verify what we can only half-suspect in real-time. Polan's work is more like an object-lesson about the dangers of totalitarian impulses: once you get it, you've got it. Each new installment shows another thing he saw, but one is tempted to ask, so what? I saw a piece of red plastic on the sidewalk today. Do you care? Probably not as much as you do about the face of that crouching boy.

Image of Mueck's Boy (1999); Image Credit: Vive le Liberté

Comments

Francesco Banda Jasso