(Image Credit: KXAN Austin)

It’s great to be back on viz. after a semester away. The more things change, the more they stay the same. Perhaps the most noticeable thing in Austin upon my return is the city’s insane rate of expansion. When one moves about town and looks at buildings, every few blocks or so there’s a new set of high rise apartments (or whatever) going in. Nowhere are the roads being widened to account for the new residents. Rush hour is literally a bunch of metallic, CO2-emitting rivers, and all this negates (at least for me) most pretences Austin makes towards modernity. I heard somewhere that 20,000 people are moving to Austin each month, although I have no idea if that’s really the case – the statistic can make one feel like they live cattle market. But to be fair, most up-and-coming cities can have that feel. Traffic rant aside, if Austin’s powers at be aren’t adjusting roadways to account for new residents, I wonder how smaller entities (such as neighborhoods, private residents, and institutions) are altering their own urban environments to account for the change. In some cases, perhaps, maybe a few brilliant environments that were designed 20 years ago are still healthy, despite all the change. In other cases, perhaps the city is designing new parks and gardens to address future public needs. I am going to try and dedicate all my viz. posts for the coming semester to landscape design in Austin. It might prove valuable, as I’m not sure these things are being catalogued anywhere else.

(Image Credit: Wikipedia)

First, a bit of landscape design history is in order. This will give my future descriptions of Austin some context, while also help us to gauge the quality of what’s being done around town. Humans have, in some way or another, been reshaping their surrounding natural environments for a very long time. Theories abound about whether or not Native Americans employed fire to clear prairie and alter forest growth. There is archeological record for controlled burnings in many areas inhabited by Native Americans, and academics debate about whether these fires were created by man or lightening. More concretely, there is amazing evidence of conscious human alteration on Easter Island, in the Pacific Ocean, where the cryptic moai statues dot the landscape. I say “cryptic” because it’s commonly agreed that the creation of the statues on the island lead to rapid and complete deforestation – a very big transformation for inhabitants of a remote island. Every single last tree on Easter Island was cut down by the Rapa Nui people and used, it is believed, to help transport new moai statues all over the island. In each of these brief examples, it’s rather obvious that landscaping practices in these locations are cultural emanations of the native populations. The Native American clearings, if they were indeed caused by humans and not lightening, might have had some practical application. If not, they were most surely part of some spiritual event. As far as Easter Island is concerned, the Rapa Nui peoples went to great lengths to dot their island with moai statues, both transforming the landscape by the statues’ addition and the trees’ rapid removal. Current anthropology holds that the moai statues were symbols of authority and power.

(Image Credit: gardensinitaly.net)

In the European tradition, pretty much all landscape design is either an elaboration or refutation of Aristotle’s thinking. Aristotle’s view of the natural world was basically that cognitive intelligence was the zenith of biological development. As such, plants were on the bottom of things and humans were on top. In the Renaissance therefore, when Classical thinking was once again in fashion, wealthy Europeans influenced by Aristotle sought to make natural environments “more beautiful” than they were naturally. This was done by subjecting groupings of plants to fit within the boundaries of planned order and proportion. So between 1550 and 1600 (sometimes referred to as the “Golden Age of gardening”) there was a massive explosion of landscape design in wealthy Italy, all of it built by cardinals vying for the papacy. We are all familiar with the white smoke bit whenever a pope dies, and how the College of Cardinals gets together to elect a successor. These days much of the rhetoric that surrounds that election has to do with spirituality and the like, but in Renaissance Italy, the cardinals tended to elect those who were most influential, wealthy, and cultured. One of the most reliable ways the college could measure the extent of these attributes in perspective candidates was through their gardens. Gardens in Renaissance Italy, after all, were one went to be seen and admired, and the wealthy owners of these gardens took delight in having others want to be in their garden. And so through all of this you get gardens such as those at Villa Farnese just north of Rome, pictured above.

(Image Credit: Wikipedia)

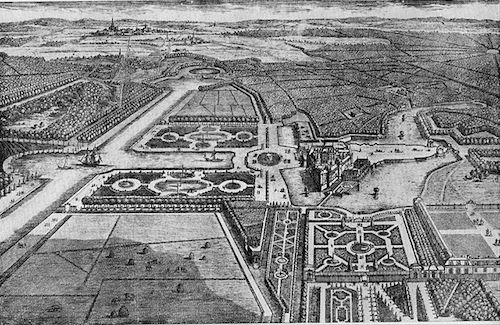

France subsequently experienced its own amazing period of garden design in the seventeenth century, when wealthy French aristocrats wanted to display their own personal wealth and culture in the fashionable ways of Renaissance Italy. Amongst a number of architects and gardeners who were designing new landscapes in seventeenth-century France, the most important was a man named André Le Nôtre. Le Nôtre, for example, had the brilliant idea to align western Paris along the Champs de Elysee, a novelty that almost every visitor to Paris appreciates, even if they know nothing of architectural history. Above you can see a seventeenth-century engraving for the gardens at Château de Chantilly, one of Le Nôtre’s later projects. The English would take all this one step further, and design gardens meant to seem as if they were completely natural emanations. Of course they weren’t “natural” – they were carefully contemplated series of plantings. But, they reflected an emerging aesthetic sense that privileged inspiration from nature over inspiration from proportion and rationality. Below you can find a photograph of the garden at Rousham, designed by William Kent in the mid-eighteenth century. It is, perhaps, the most successful eighteenth-century English landscape garden.

(Image Credit: rousham.org)

I’m already nearly 500 words over my target length. In closing, then, I’ll end by saying that over the coming semester, I will attempt consider landscapes throughout Austin through the full lens of landscape design history. Some will conform, others no doubt won’t, and I’ll consider the implications of all these variations. At the fore will be a preoccupation with the extent to which horticultural work in and around the city makes rhetoric gestures, and the extent to which those gestures are conscious of Austin’s ongoing transformation.

Comments

Easter Island's "eco-crisis"

NPR did a great story on Easter Island's "eco-crisis" and what it means for human development and our natural environs these days. Robert Krulwich ruminates on the real cause of deforestation on Easter Island and shatters a few myths about its inhabitants at the time of the European encounter. It's worth checking out and perhaps considering in terms of your larger argument:

http://www.npr.org/blogs/krulwich/2013/12/09/249728994/what-happened-on-easter-island-a-new-even-scarier-scenario