Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

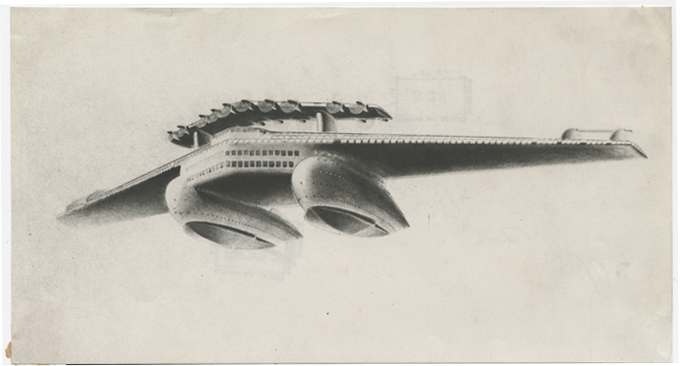

Norman Bel Geddes, Airliner #4 rendering, ca. 1929-1932

Touring the Harry Ransom Center's Norman Bel Geddes exhibit a few weeks ago, my fellow viz. staffers and I were struck by how many of the designer's projects never made it past the drawing board. Bel Geddes' sketches of giant, amphibious aircrafts (see "Airliner #4" above) are prime examples of the far-fetched schemes his studio was hatching in the 30s alongside commercially viable designs, like this handsome pair of seltzer bottles featured in an earlier post. But, as other viz. contributers this week have remarked, articulating what is not and will never be seems like an inevitable part of a theorizing and designing the future. It certainly makes strolling through the Ransom Center's "I Have Seen the Future" exhibit feel like a trip into a delightful, hybrid world of fiction and history.

Geddes' plans for airborne commercial and recreational spaces (the 451 passengers aboard the flying machine, above, would have access to a gymnasium and a full orchestra) interest me because they present a counterpoint to the "auto-centric America" with which Geddes' work is usually associated. It's likely that Geddes' designs influenced both American aviation and automotive systems, but for an untrained industrial designer like Geddes, the first of these frontiers must have seemed significantly more difficult to modernize, if only from an engineering standpoint. The challenge of hoisting into the air a full spectrum of modern amenities makes Geddes' airplanes look almost cartoonish. Yet, when we recall that the horizon of space travel was not so far off, Geddes' airliners look less dream-like than before.

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Norman Bel Geddes, Motor Car No. 9 (with tail fin), ca. 1933

Geddes' concepts for land vehicles, even, borrow design elements from the skies. Like a plane, this motor car is both winged and streamlined so as to travel swiftly down the chute-like highways that Geddes envisioned for cities of the future.

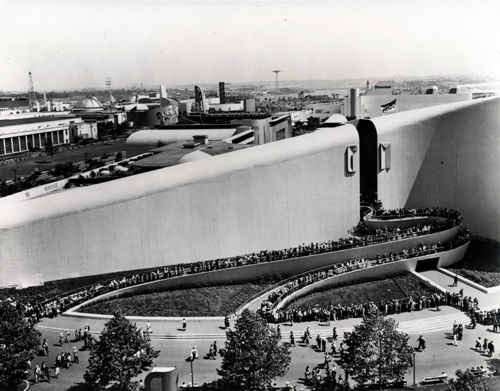

Moreover, several of Geddes' larger projects play with ideas of suspension and aerial perspective. The people entering the General Motors building (pictured below), which Geddes helped to design for the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair, look as though they're levitating as they stream into the exhibit on a swirly staircase. The shape of the ramp reflects the free-flowing highway system that Geddes' Futurama exhibit proposed as a solution for urban congestion. (The Futurama exhibit was housed by the GM building, below.) It also mirrors the building's uppermost edge, the slope of which resembles the path of an airplane at lift off. The structure clearly employs the architectural metophor of slope to signify scientific progress, economic growth, and/or social mobility for commercial and nationalistic purposes.

Image Credit: thefrailestthing.com

Image Credit: The Harry Ransom Center

Bel Geddes' famed Futurama installation, the focal point of GM's "Highways and Horizons" World's Fair pavilion, required a mobile, aerial perspective to be fully absorbed by its spectators. Visitors were conveyed around the model on a track positioned above the miniature city. Because the onlookers studied the cityscape from the perspective of a plane, during a time when private flights were uncommon--and commercial aviation nonexistent--Geddes' exhibit must have been doubly displacing for its viewers. Glimpsing at an urban future that prized efficiency, utility, and mobility surely presented them with a unique experience. But apart from that, the shifting aerial vantage point that the ride simulated must have seemed marvelous and novel in itself, since it is unlikely that many of Futurama's spectators had ever hovered over any city--past, present, or future.

General Motors, Futurama Spectators, ca. 1939

Image Credit: Screenshot of Google Maps

I now want to hover over another modernist city--a real one that happens to be the capital of Brazil. In 1956, when the Brazilian President commissioned Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer to build Brasília, the nation's new capital seat, the architects had already collaborated on another definitive modernist project: the award-winning Brazilian pavilion at the 1939 New York World's Fair. (As you will recall, this particular World's Fair was also the site of Bel Geddes' Futurama exhibit.) Beyond this instance of proximity between the designers' work, there are additional interesting parallels between Bel Geddes' vision and the mature designs of the Brazilian duo. The Brasília project, for instance, literalizes Bel Geddes' bird's-eye conception of the modern city by organizing the city's roads and structures in the shape of a plane (see the Google Maps image above). A decade-and-a-half after Bel Geddes used aerial perspective to show that cities could be planned and networked with well-designed infrastructure, Costa and Niemeyer memorialized the airplane--a symbol of transcendent viewpoint (?)--within the structure of a modern metropolis.

When you visit the "I Have Seen the Future" exhibit at the Ransom Center, as I hope you will, do not despair that the miniature buildings of the Futurama exhibit remained forever in the realm of fantasy, like the buildings of present-day Legoland. Brasília is a very real place that, at ground level, shares Bel Geddes' modernist aesthetics, and from the sky, pays tribute to a globalized present that indeed has been shaped by aviation.

Image Credit: uccla.net

The viewpoints expressed in this blog post are strictly those of viz., and do not in any way represent the opinions of The Harry Ransom Center.

Comments

Brasilia

You don't see a hummingbird????

aerial Brasilia and the hummingbird

I've heard the city of Brasilia is supposed to resemble an airplane or a hummingbird from the air, but I can't seem to find a source for this assertion. Perhaps readers might be able to point me in the right direction?