Image Credit: NASA

With the recent passing of Neil Armstrong, the decommissioning of the space shuttles, and the release of the latest "deep field" image from the Hubble Space Telescope, the rhetoric of space imagery has been on my mind. Except for the occasional "why waste money on this?" argument, astronomical images find wide appreciation, appreciation which I certainly share. However, I also see a certain risk in the arguments made using space imagery that can be lost amidst the optimism and wonder.

The truism of an image speaking a thousand words falters before a photo like the one above where the immensity of space threatens to swallow all words. The Hubble eXtreme Deep Field is a compilation of observations of a small section of sky. As science writer Phil Plait says, even in such a small section, the telescope captures over 5000 galaxies, each with billions of stars.

The human mind cannot begin to understand such size and scope. Plait admits, "We humans, our planet, our Sun, our galaxy, are so small as to be impossible to describe on this sort of scale," yet he insists, "that's a good perspective to have." He goes on:

...we figured this out. Our curiosity led us to build bigger and better telescopes, to design computers and mathematics to analyze the images from those devices, and to better understand the Universe we live in.

And it all started with simply looking up. Always look up, every chance you get. There’s a whole Universe out there waiting to be explored.

Images somewhat closer to home more easily inspire human-scale arguments. Some see in the view of Earth from space an argument for human unity and concern for our environment, and these are common views from those who have made the trip into orbit. Such images first came to prominence during the Apollo missions, especially with "Earthrise" taken by William Anders during Apollo 8's mission to orbit the Moon.

Image Credit: NASA, William Anders

The image shows a small but vibrantly blue and white Earth set against the blackness of space and rising above the gray, rocky surface of the Moon's horizon in the foreground. Frank Borman, the commander of Apollo 8, remarked:

When you're finally up at the moon looking back on earth, all those differences and nationalistic traits are pretty well going to blend, and you're going to get a concept that maybe this really is one world and why the hell can't we learn to live together like decent people. (quoted in Denis Cosgrove's Geographical Imagination and the Authority of Images p. 22)

Image Credit: NASA

The "Blue Marble" and "Blue Marble 2012" offer closer perspectives of Earth's land, sea, and air unmarked by the political divisions of national borders.

Image Credit: NASA

Seeing these images, I find the unifying argument of an astronomical perspective enticing but also risky. If humans ever move out into space in any number, I think it likely that we'll take the full range of our social baggage with us, the values and ideas that inspire both justice and injustice. The risk lies in the tendency for factional interests to disguise themselves as universals. "The people of Earth" as a concept works well in the abstract, but it can obscure the contradictions that abound within that identification. Take, for example, the plaque left on the base of Apollo 11's lander.

Image Credit: NASA

The plaque bears the signatures of the three mission astronauts: Armstrong, Collins, and Aldrin. It also bears the signature of then-president Richard Nixon. (Sometimes I wonder if, in our distant future, some civilization, which has the ability to translate written English but lacks historical knowledge, might, in its exploration of the Moon, conclude that Nixon was among the first people to make the quarter million mile journey.)

The plaque speaks to American audiences and audiences the American government wished to address, though it gestures toward a global ethos by including images of the eastern and western hemispheres. The text reads, "Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon, July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind." That stated intention of peace contrasts with the geopolitical exigencies of the Cold War that drove the space program. During this peaceful mission, when Nixon spoke to astronauts on the moon from the Oval Office, he was also ordering the bombing of Cambodia and oversaw other campaigns in the Vietnam War – itself another event tied to the Cold War. I don't mean to suggest that the Apollo program was not peaceful in itself, but it existed within a complex set of relationships between war and peace and between the peoples of the Earth that an overly optimistic perspective can obscure.

Perhaps unity, then, may not be the best argument to construct from the visual products of our space explorations. Or, at least, not unqualified and decontextualized arguments for unity. A contextualized argument can be found somewhere between the unthinkably vast scope of the deep field image and the almost familiar views of Earth from orbit.

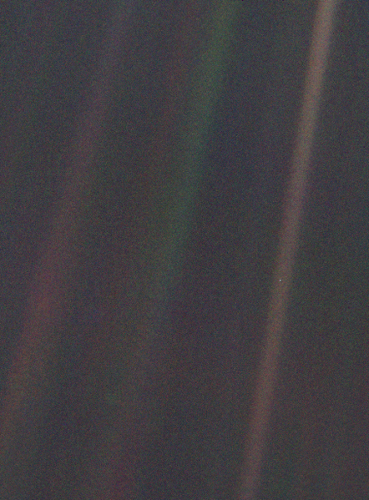

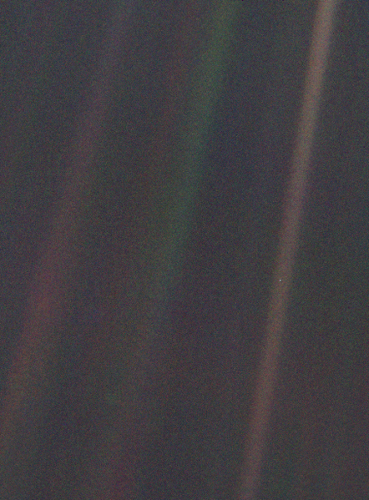

Image Credit: NASA

The Voyager 1 probe took this "Pale Blue Dot" image of our homeworld when it was some 3.5+ billion miles from Earth in 1990. Earth appears as a barely noticeable point (0.12 pixels according to Wikipedia) in the right-most bar of sunlight set against the void. Carl Sagan had asked NASA to take the photo. In his book Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space, Sagan offered an argument that speaks to a hopeful future while it also acknowledges tragedies past and present and the considerable challenges we face even with the suasive potential of astronomical images:

From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest. But for us, it's different. Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that in glory and triumph they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner. How frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity – in all this vastness – there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. The Earth is the only world known, so far, to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment, the Earth is where we make our stand. It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago