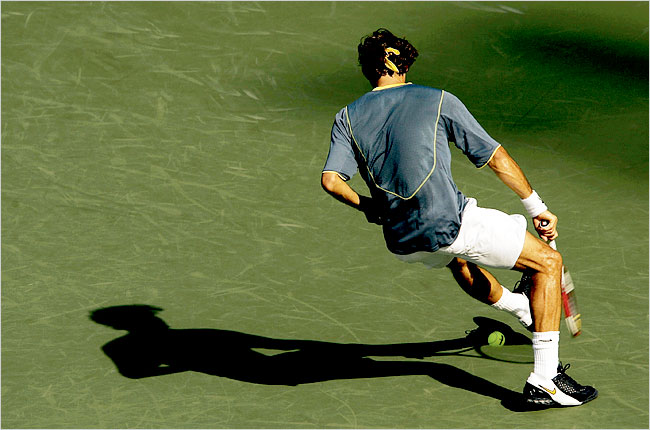

"David Foster Wallace mii Playing Tennis" — Image Credit: Nick Maniatis, via Kottke.org

My first spring in Texas left me nostalgic for my Kentucky roots. This, of course, meant I’ve spent the last few weeks watching entirely too much March Madness. For Kentuckians, without a single professional sports team to call their own—and without Texas-sized performance and investment in college football—college basketball is a powerful source of sports identity. The showdown between the University of Louisville and the University of Kentucky in this year’s Final Four was an epic, almost state-shattering event.

I’m not much interested in halftime banter or commercial breaks, however, so the last few weeks have also included a good deal of channel surfing. As I surfed, I found myself catching glimpses of another sport I’ve always wanted to watch more of but never have: tennis. My potential interest in tennis has nothing to do with fond remembrances of my single season as a high-school tennis player (I was horrible). It’s a theoretical interest that is largely indebted to David Foster Wallace. Tennis figures prominently not only in Wallace’s well-known novel Infinite Jest, but in his essays.

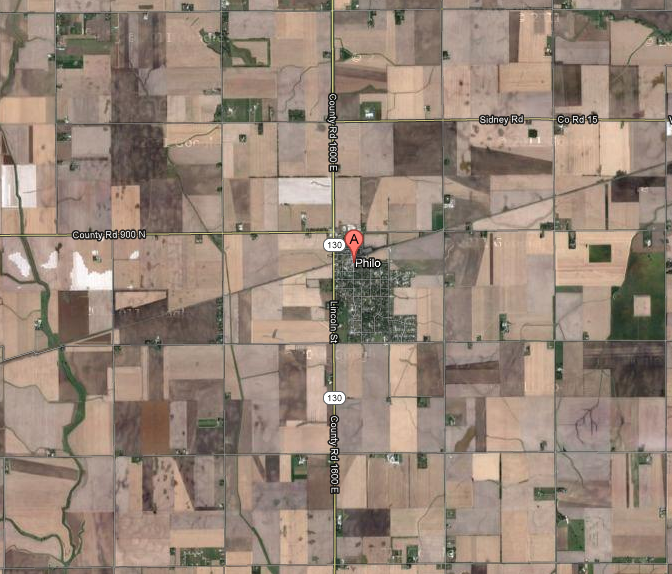

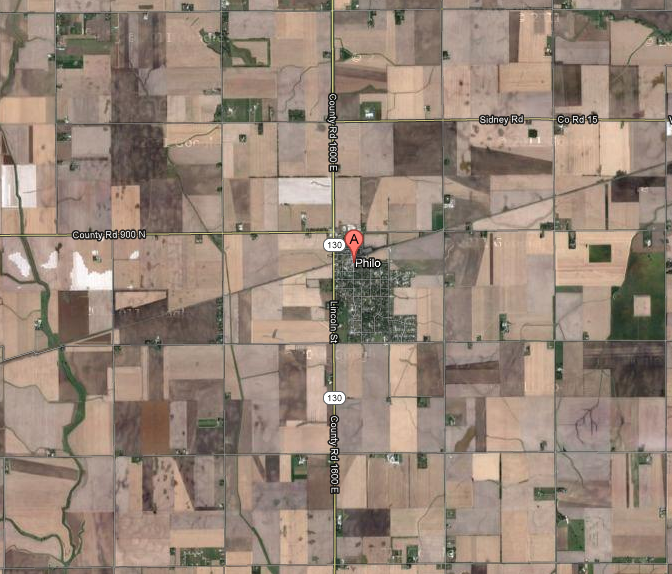

The first piece in Wallace’s A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again sets the tone. The essay, “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley,” comprises a series of personal reflections on Wallace’s tennis-heavy upbringing in central Illinois, but is also a keen look at the visual tableaux and mathematical geography that made up his childhood landscape. Reflecting on his move from IL to Massachusetts, Wallace writes, “I’d grown up inside vectors, lines and lines athwart lines, grids—and, on the scale of horizons, broad curving lines of geographic force, the weird topographical drain-swirl of a whole lot of ice-ironed land that sits and spins atop plates” (3). Consider an aerial view of Philo, Wallace’s hometown:

Image Credit: Google Maps

Lines abound. Wallace’s later description of the town is utterly mathematical—in one sense exhaustively literal, and in another wonderfully metaphorical: “Philo, Illinois, is a cockeyed grid, nine north-south streets against six northeast-southwest, fifty-one gorgeous slanted-cruciform corners (the east and west intersection-angles’ tangents could be evaluated integrally in terms of their secants!) around a three-intersection central town common with a tank whose nozzle pointed northwest … plus a frozen native son, felled on the Salerno beachhead, whose bronze hand pointed true north” (8). Wallace attributes his success as a young tennis player to his intuitive affinity with this environment and its mathematics.

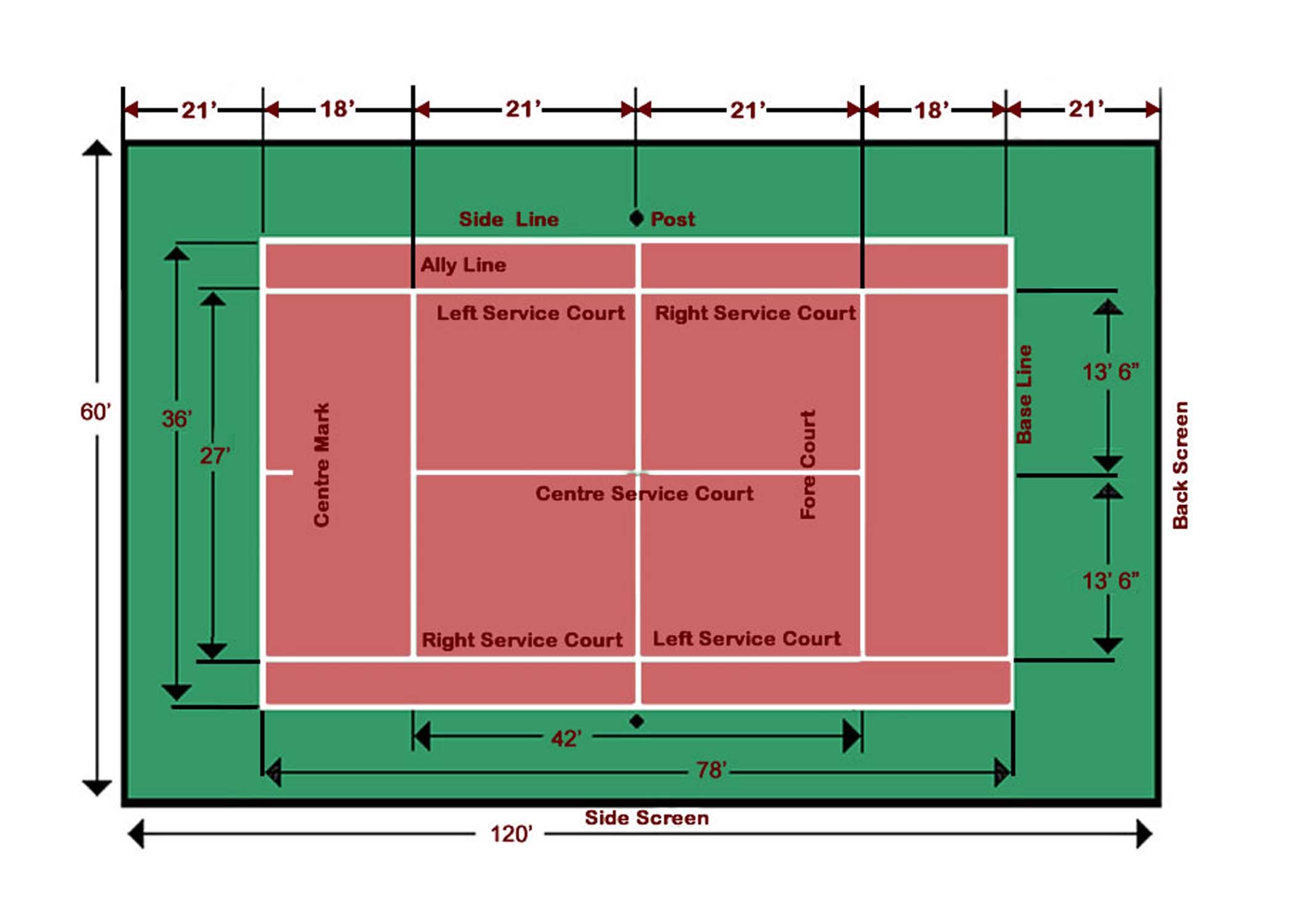

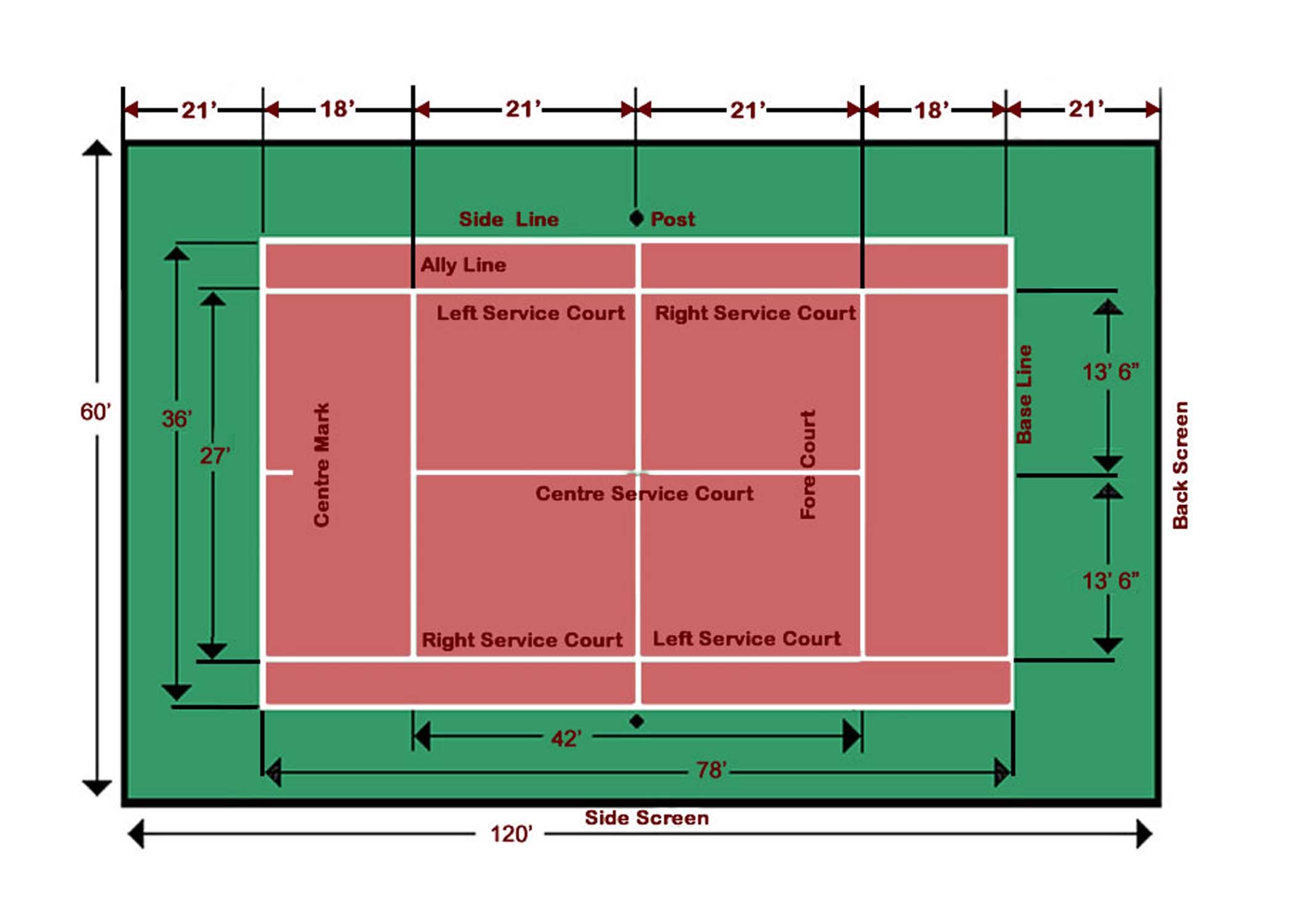

Image Credit: Tennis Help For Beginner to Pro

The mathematical precision of the ideal court lent him some theoretical edge, but it was the vagaries of central Illinois courts and weather that really gave him his advantage: “I’d found a way not just to accommodate but to employ the heavy summer winds in matches” (14). The “wind and bugs and chuckholes” of central Illinois’ unkempt courts were not resented imperfections for Wallace, but “a kind of inner boundary, my own personal set of lines” (15).

Image Credit: Photos Public Domain

When I see the court above, I think of the decay of suburban sprawl. For Wallace, it might be something strangely wonderful, a geometric set of “deformities to play around” (15).

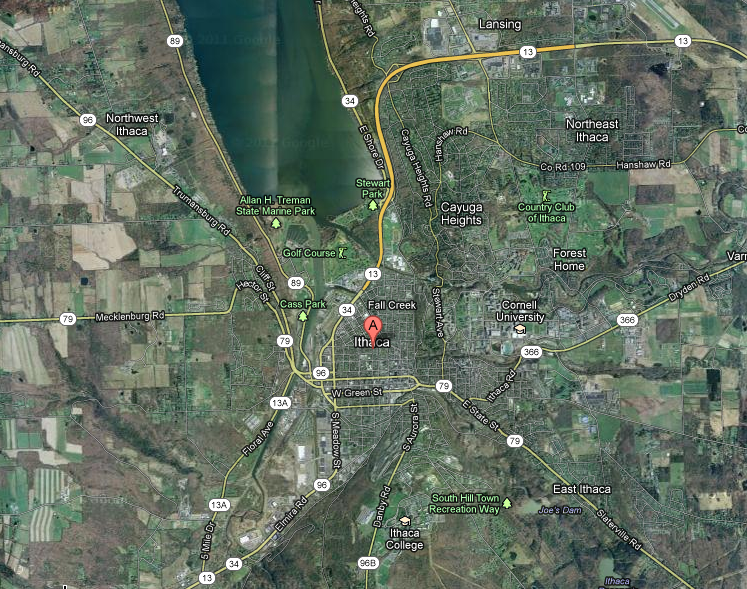

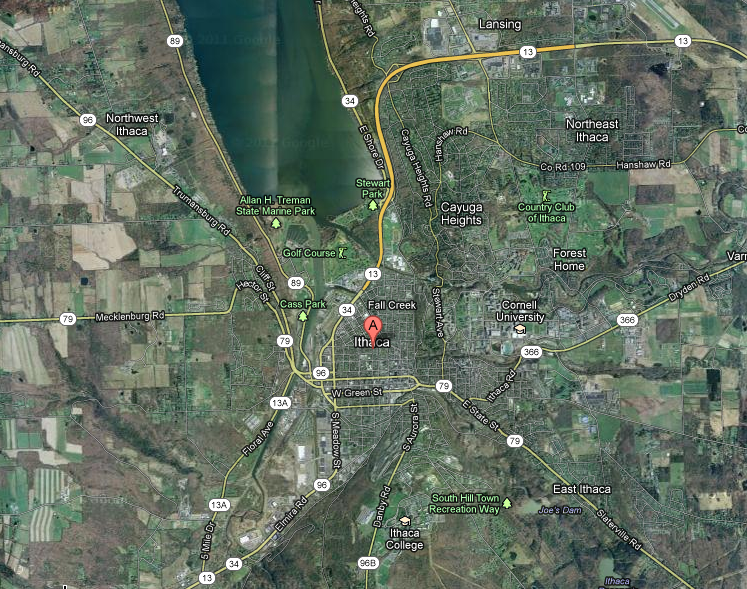

Wallace speculates about the origins of his preternatural symbiosis with his environment: “I’d known, even horizontally and semiconsciously as a baby, something different, the tall hills and serpentine one-ways of upstate NY. I’m pretty sure I kept the amorphous mush of curves and swells as a contrasting backlight somewhere down in the lizardy part of my brain, because the Philo children I fought and played with, kids who knew and had known nothing else, saw nothing stark or new-worldish in the township’s planar layout, prized nothing crisp. (Except why do I think its significant that so many of them wound up in the military, performing smart right-faces in razor-creased dress blues?)” (8-9).

“Wallace’s birthplace, Ithaca, NY, via satellite” — Image Credit: Google Maps

“Ithaca at eye-level” — Image Credit: Budget Travel

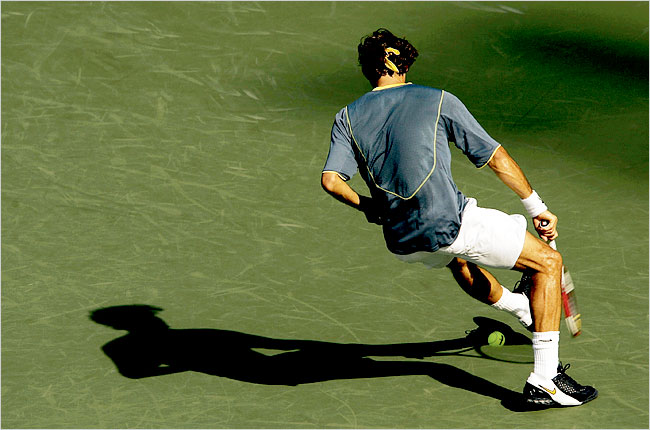

Psycho-geographical ruminations aside, Wallace returns to the visual nature of tennis in one of his last published works, “Roger Federer as Religious Experience.” Published in the New York Times in August of 2006, the Federer piece positions Wallace as spectator rather than player. His sharp eye for the game, however, remains. The online iteration of the story is accompanied by such images as

Image Credit: NYTimes.com

The dynamic virtuosity suggested by such an image is powerful, though Wallace might see the image as a poor reflection of Federer’s platonic perfection. He notes, “An athlete’s beauty is next to impossible to describe directly. Or to evoke.” Words fail, in other words. And so does televised tennis, which “is to live tennis pretty much as video porn is to the felt reality of human love”: “[A] TV screen’s image is only 2-D,” squashing the tennis court’s length and thus failing to capture the speed of a professionally-struck tennis ball, which “in person is fearsome to behold.” TV might capture Federer’s intelligence, “since this intelligence often manifests as angle,” but not the sacred beauty of his play. And I might capture Wallace’s intelligence via blog post, but I’d be remiss not to recommend that you encounter his tennis writing for yourself.

Wallace, David Foster. “Derivative Sport in Tornado Alley.” A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again: Essays and Arguments. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1997. 3-20. Print.

---. “Federer as Religious Experience.” New York Times. New York Times, 20 Aug. 2006. Web. 30 Mar. 2012.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago