Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

It's a bit surprising to walk into the Harry Ransom Center's current exhibition on the King James Bible and see Marc Chagall's Exodus series on display, but, considering his origins in a Hasidic family, the Jewish artist's works are a surprising addition to any gallery. Chagall's work was an uncomfortable subject for his parents and, later, his in-laws--telling your Hasidic parents that you're going to grow up to be a painter is a bit like telling religious Christian parents that you're going to be a stripper. Despite shocking his parents by painting nudes, Chagall would continue his work to become the foremost Jewish artist of the 20th century, earning respect from his contemporaries for his understanding of color and his ability to use a limited palette with eye-popping results.

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

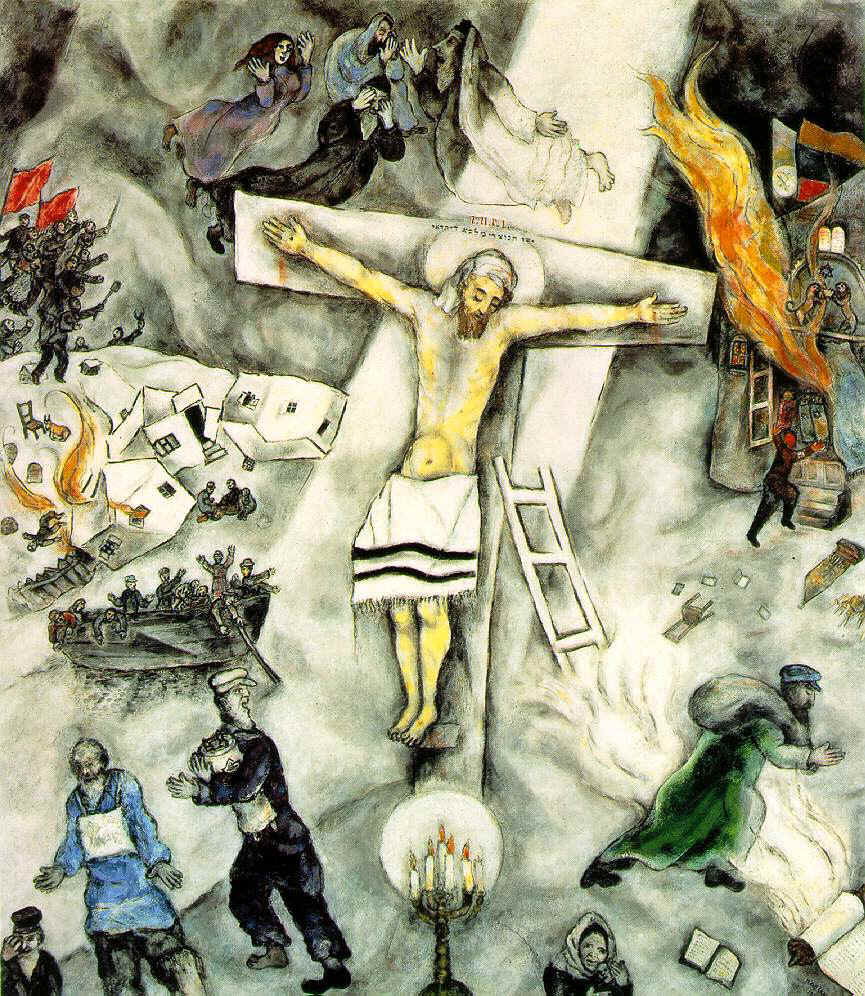

The first image in this post is the frontispiece for 24-print collection entitled The Story of the Exodus, published in 1966. The image above shows Exodus 2:11, in which Moses witnesses the sufferings of the Jewish people enslaved and forced into hard labor by the Egyptians. In the story, Moses kills an Egyptian when he sees the man beating one of his people, the beating here represented by the violent red and hands with whips in the top right corner. The violence and suffering here is dreamlike, as all of Chagall's work is--the people's suffering in this image is represented by a dreamy thought bubble emanating from Moses's righthand horn.

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

Working during the Second World War and afterwards coming to terms with what happened, Chagall's works, like the works of many artists in the first half of the 20th century, reflect the bafflement and impotence of watching the Holocaust happen from afar. Chagall was lucky to get on the list of European artists that some United States officials were trying to save, and, unlike Picasso and Matisse, he did leave Vichy France in 1941.

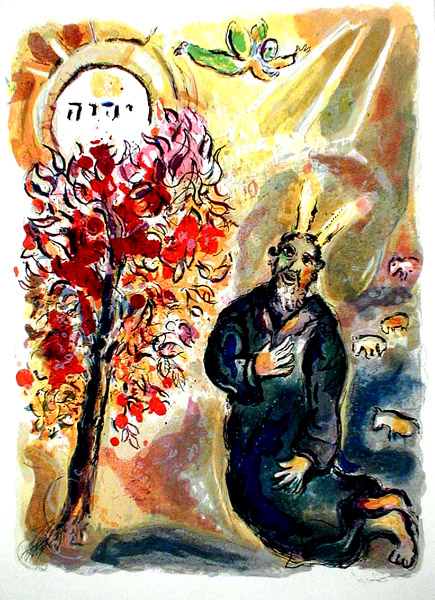

Interestingly, Chagall colors (literally) these prints with bright optimism for an ancient future, even after the Holocaust. The above image, another beautifully colored one, shows Moses at the burning bush, where God, after becoming concerned about the sufferings of the people, appointed Moses to lead the Israelites out of oppression and to the land of milk and honey.

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

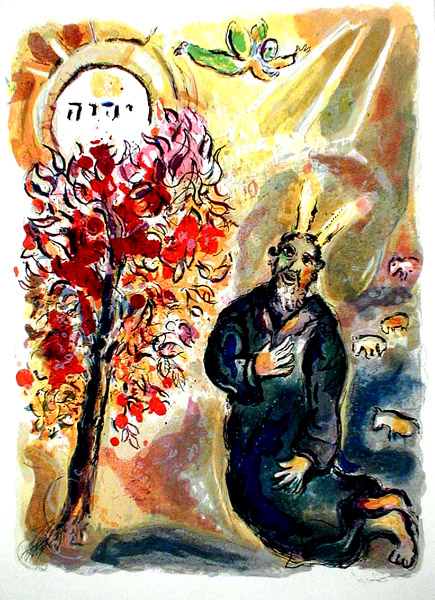

After Moses asks how he is to prove that God sent him to the Israelites, God turns Moses's staff into a snake, as in the image above. Each image shows the influence of Chagall's works in gouache, used not in these prints but in his other works. Gouache is much like watercolor, but contains an opaque base in order to create a brighter, opaque color. The limits on painting in gouache (as well as the benefits) are reflected in the spots of color in this image even though it's a lithograph.

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Art Institute of Chicago

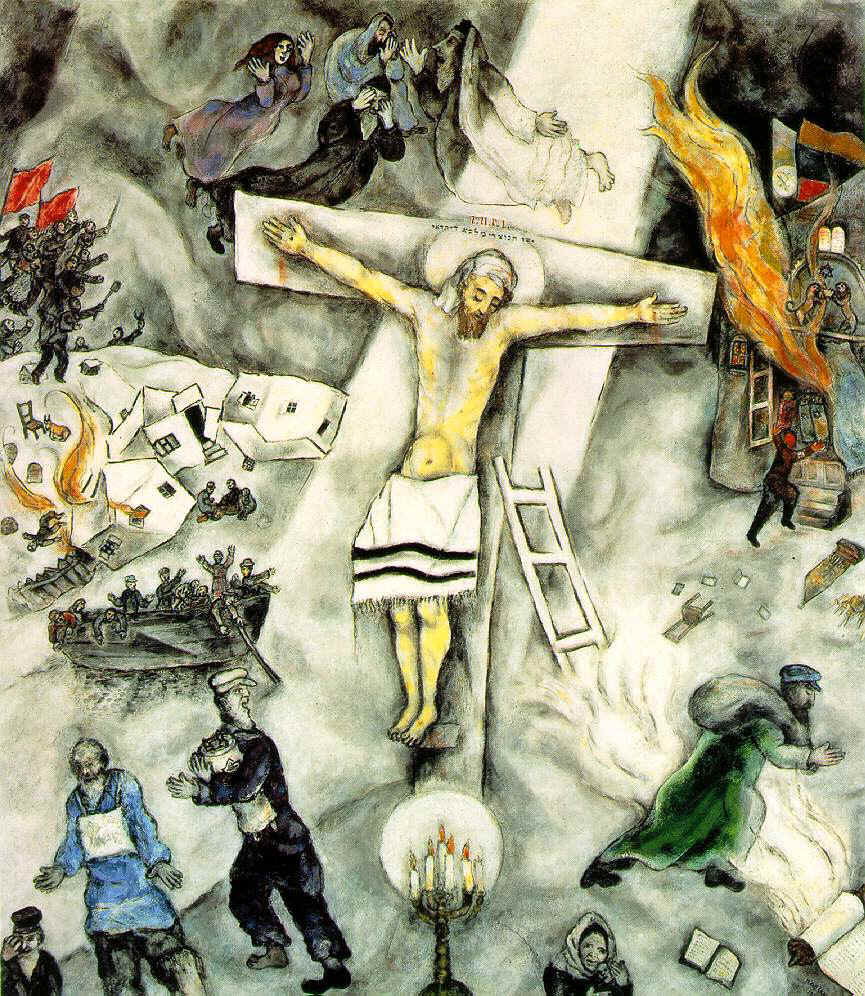

The Exodus prints are part of a larger trend in Chagall's religious works. From 1931 until 1956, he worked to illustrate the Bible; later, he would turn to crucifixions in order to best express tragedy. This last image, The White Crucifixion, is not from the series at the Harry Ransom Center, but understanding this crucifixion is important to understanding the importance of Exodus series and the rest of Chagall's work.

Chagall believed no artistic subject expressed suffering as well as a crucifixion. (For a fictionalized account of a Jewish artist painting a crucifixion, Chaim Potok's My Name is Asher Lev is worth a read. It gets at the depths of pain that would cause a Jewish artist to paint a Christian form.) Though it's generally used by Christian artists, Chagall uses this crucifixion to express the persecution of the Jewish Jesus specifically and of the Jewish people in the 20th century generally. In the top left corner, one can see communist soldiers coming to terrorize Jews, in the top right, a soldier burns a synagogue in Lithuania (the soldier originally wore a swastika on his armband).

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

Image Credit: Marc Chagall via Spaightwood Galleries

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago