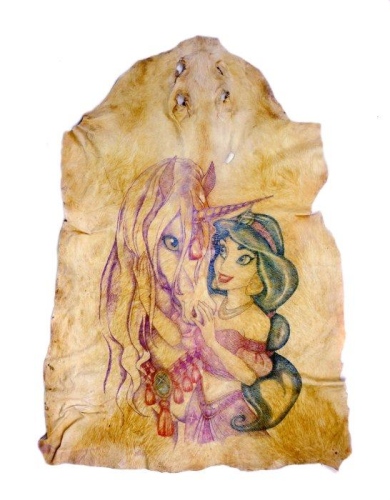

(Image Credit: Wim Delvoye)

It's pretty easy to understand (and probably join in) the outrage surrounding Wim Delvoye's work with pigs. Tattoos aren't exactly taboo in any real fashion anymore, but even as commonplace as they've become they still seem to provoke discussions about the use of bodies as writing platforms. In casual conversation clothes don't have nearly the same effect; though, it could be argued that they write on the body just as much as any tattoo. Clothes, though, seem to be commonly taken up as transient while tattoos are (mostly) permanent. I doubt there would be nearly as strong a reaction to these pigs if they were just dressed up on a daily basis.

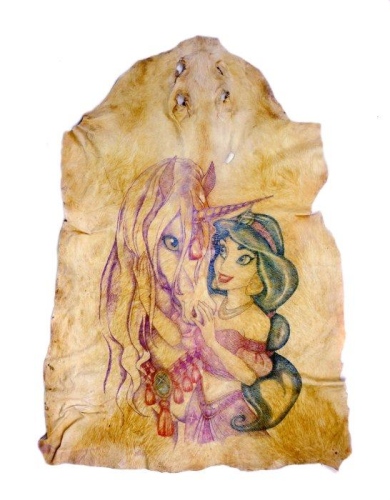

(Image Credit: Wim Delvoye)

Of course, dressing a pig everyday would surely, almost undeniably, have a more noticeable impact on a pig's life. Clothes, no matter the degree to which a body has been naturalized to their presence, always remain external; through a thousand tiny hitches they make their presence known--they bind, sag, ride up, get caught, twist, shift, shuffle, flap in the wind. We put them on, we take them off; they are a forceful presence in our lives, but we do change them (What does this say, then, about, the 1% of America that isn’t allowed to change their prison uniforms?). And while there's lots of fun poked at animals wearing clothes (and at the people that dressed them) I don't believe there is anything near the response these tattooed pigs elicit. It's worth interrogating this difference.

(Image Credit: Wim Delvoye)

"To tattoo a pig, we sedate it, shave it and apply Vaseline to its skin" (Delvoye in a 2007 interview in ArtAsiaPacific found at Sperone Westwater). And then the pig and tattoo grow together. Grow, as Delvoyne imagines, in both size and value together. Pigs, posits Delvoye in the same interview, are largely thought of as having very little value. And even though these pigs may be spoiled they aren't co-authors in this project. Delvoyne states that "Yes, we name them; the name is often tattooed on the pig. It’s part of the personalization of the industrial product" (Delvoye). The pigs are breathing canvases. They shift and alter the tattoos they carry, but they are always still, fundamentally, written on. The pigs are eventually slaughtered for their skins. In the end they are either stuffed and mounted, or the skins are displayed.

(Image Credit: Wim Delvoye)

Wim Delvoye worked his way up to live pigs. In the 1990s he began tattooing dead pigs, just working with pig skins he acquired from slaughter houses. It wasn't until 1997 that he worked with a live animal. In the late 90s he worked with and on a number of different pigs in different places. In 2004 he moved his practice to China and subsequently established Art Farm, a pig farm where raises and tattoos his pigs. It's worth noting that the other project Delvoye is known for is “Cloaca” a 39 foot long machine he built that eats, digests and shits.

(Image Credit: Wim Delvoye)

Delvoye is a vegetarian, but he both consumes and offers these pigs up for consumption as art. He's particularly apt in describing that "I prefer to show the pigs alive. In a perfect world, I would just show the Cloaca shit machines and live pigs—eating and excreting together" (Delvoye). The constructed shitting machine and the thoroughly marked pigs are rendered equivalent, both flattened out as spectacle. The tattooed pigs are conceived as part of an industrial machine, a machine made up by human, animal, machine, and conceptual bodies. Taken together the pigs and machine reposition the viewer as also taking part, "eating and excreting" pigs and machines both.

Next week I’ll be writing on an already thoroughly inscribed upon birthday-present-pig that’s part of The Harry Ransom Center’s exhibit The Greenwich Village Bookshop Door: A Portal to Bohemia, 1920-1925.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago