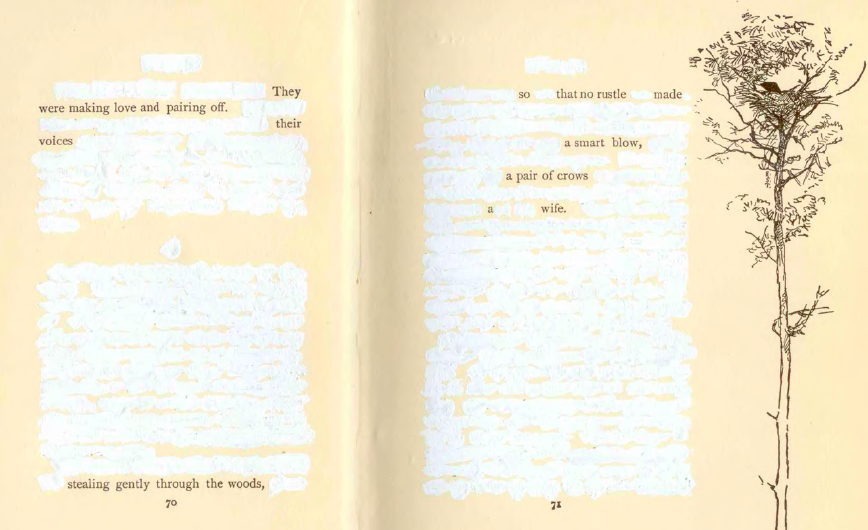

Screen shot, Susan B.A. Somers-Willett, Wild Animals I Have Known pamplisest via Landmarks

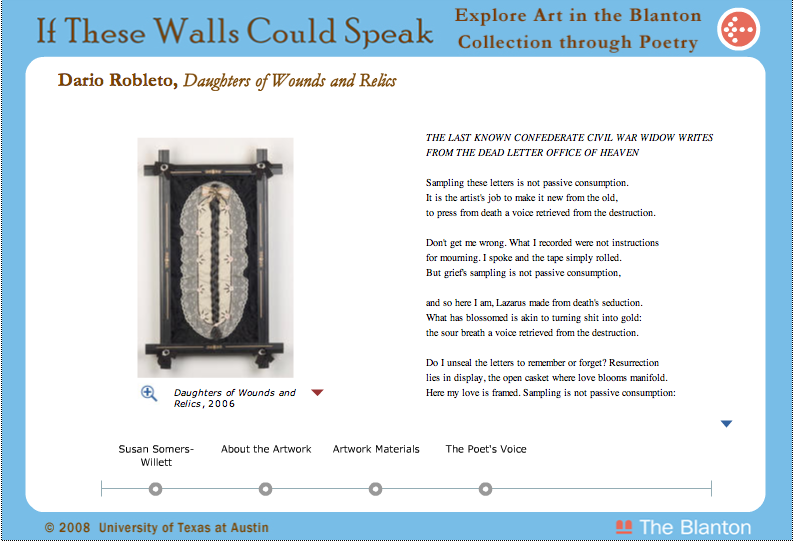

Last week I posted Part I of my interview with Susan Somers-Willett. Today I'm excited to bring you Part II in which we continue to talk digital poetics and new uses of ekphrasis. Susan holds forth on other projects, including her work with UT's Landmarks prorgram and the Blanton Museum's poetry project. We also discuss her upcoming work that responds simultaneously to the recent Abu Ghraib photographs and early 20th-century lynching photographs.

EF: Do you think this kind of hybrid medium (poetry, photography, web content) will proliferate as we move more into digital poetics and digital modes of access? What kind of multimedia poetics do you find to be engaging?

SSW: Yes, I do. I think Kwame Dawes’s work is really exciting. He’s working in a similar mode of going into various communities, and documenting people or events within those communities, though I don’t know how much audio work he’s working on right now. His pieces have him reading the poem, so adding the element of interview footage was unique to my project and Natasha Trethewey’s project and what Erika Meitner’s project will become.

I feel like we’re on the verge, as Kwame’s, Natasha’s, and Erika’s projects will inspire people to approach this in a different way. It’s not like this is completely new mode of expression. James Agee and Walker Evans’s collaboration Let Us Now Praise Famous Men is probably the most famous example, but clearly there’s not a digital element to that. I think as far as the combination of audio and video and textual production goes, the more publishing becomes easier and more accessible through technology and our use or misuse of it, we’re going to see more of it. It’s a very specific combination. Poetry, audio, photography. Text, sound, image. I probably just need to think a little outside the box on that. Such a trinity doesn’t necessarily have to have a documentary focus.

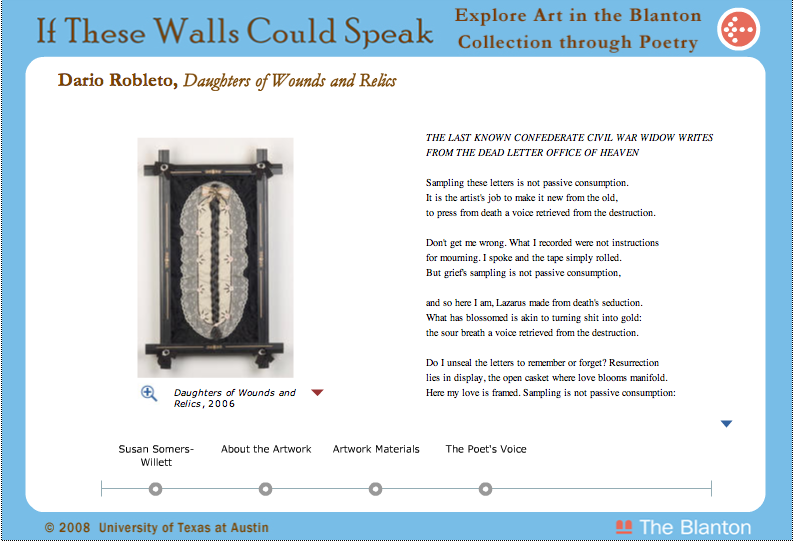

For instance, consider what they did with the Blanton poetry project. You have the piece of artwork, the poem, and the interview with the project. There’s also the Landmarks projects at UT.

Screen Shot, Susan B. A. Somers-Willett, collaboration with the Blanton poetry project

EF: Could you talk a bit more about your involvement with Landmarks?

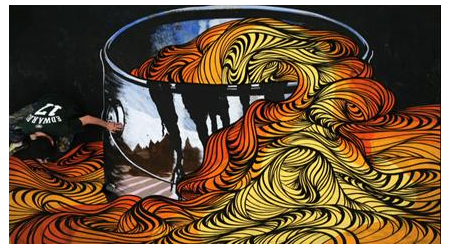

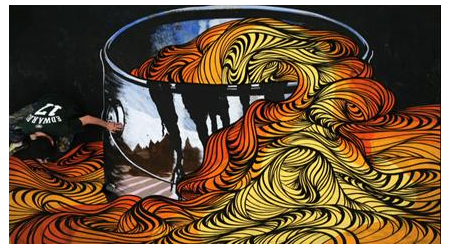

SSW: Let me explain what I think I did, because I really don’t know what I did. I called what I did for Landmarks my “bonkers poem” because it was drawing on so many different elements at which I was surely unadept. They asked me to respond to the piece by David Ellis that he created at UT in a period over a month called Animal. What he does in terms of his process—David has a large oversized canvas, a high res. camera that’s over the piece of canvas or surface, and he paints on the floor and he paints an entire mural, and then he paints over it, and then over it, and over it again while the camera captures the entire process in time-lapse photography. In the resultant video, David’s painting starts to morph and change, and then you see elements of the old painting showing through either because the paint is translucent or he has left elements that would read as blank space but they’re not blank space. It’s just the old showing through in the new. And the final piece is a 9-minute video of him doing this process for a month. When I saw it for the first time, it blew my mind and then I thought, “How the hell will I write about this?” It’s so ephemeral and, well, bonkers. If I were to approach it in the traditional ekprhastic way, it would be like taking stills from a film and trying to describe those scenes, but that doesn’t capture the excitement or energy or beauty of what David is doing in his work. It would be textbook.

Screen shot, David Ellis, video still from Animal, via Landmarks

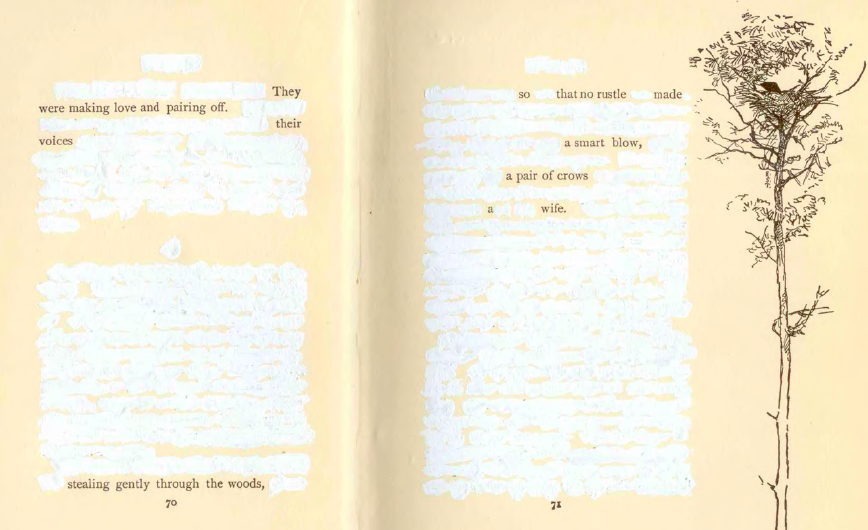

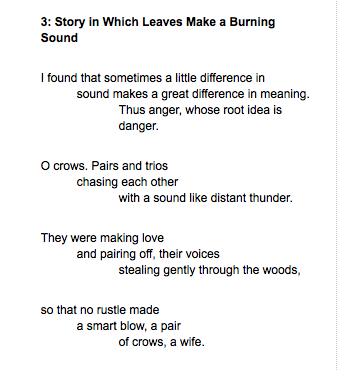

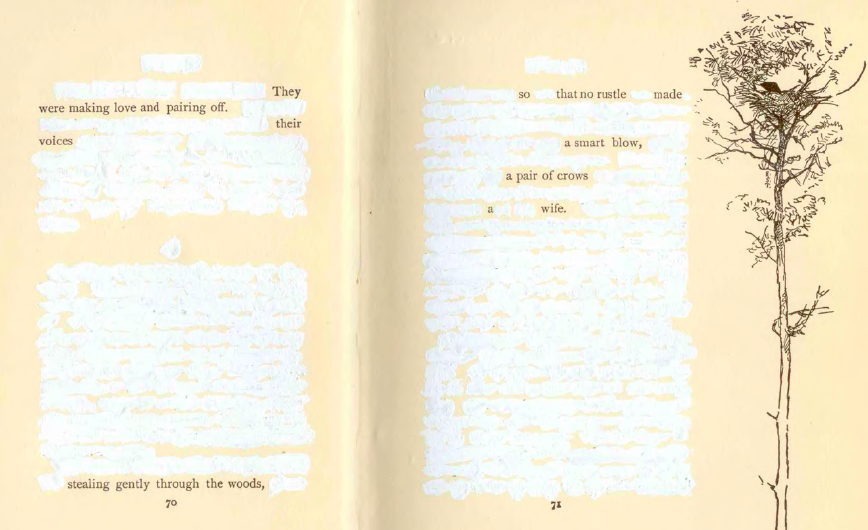

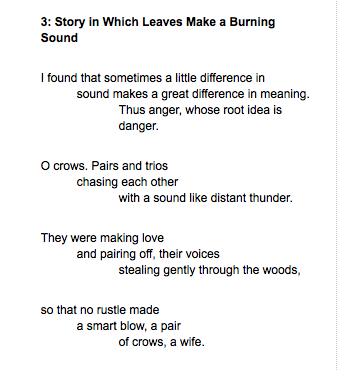

I decided to approach it from the angle of David’s process and apply that process to my own work as a writer. One thing that came to mind, one concept, was the palimpsest. I was thinking of erasure, writing under writing, a new poem that’s showing through old writing, the old painting showing through the new paint that’s on top of it . I looked for examples in literature that modeled that paradigm, and I thought of Mary Ruefle’s A Little White Shadow where she’s taken a 19th- century novella and taken Wite-Out® and erased certain parts of it so that on each page of that book, there splays a little poem. It’s like haiku, but not syllabic. Her poems in that book are shaped by whatever words are on the page. I read that and it was so exciting, experimentally, but incredibly accessible. So with David’s piece and then with Mary Ruefle’s model in mind, I created the poem Wild Animals I Have Known. There are other pieces in the same vein such as Travis MacDonald’s "The O Mission Repo" that uses redaction as its method. Ruefle’s book and the tradition of erasure in visual art and in performance art in which artists will cut out something or burn something to create were my main inspirations.

I decided to find a source text that corresponded with David’s piece Animal, and I wanted the source to be local, because David’s text stemmed from images that he saw in Austin and included some ambient sounds associated with Austin. I did a search in the HRC [Harry Ransom Center] to see what they would have associated with animals, specifically crows or grackles. I was so haunted by the image of a grackle in David’s piece. I found a book that had to be public domain, and I came across this text Wild Animals I Have Known by Ernest Thompson Seton. In that collection of nature stories, there was a story called “Silverspot the Crow,” and I got my hands on a couple of original texts of that book and decided to use redaction in the spirit of David’s piece. But, I wanted to make it read as a whole. I didn’t want it to read in just parts like other poets had done, in a one-poem-per-page, haiku-like fashion. I wanted to create a poem that would, through the process of redaction, span the entire length of the piece and tell a narrative like David’s piece. So, it became a sectioned poem, but the stanzas are created page by page, so one stanza is one page.

Screen shot, Susan B.A. Somers-Willett, Wild Animals I Have Known pamplisest via Landmarks

Screen shot, Susan B.A. Somers-Willett, stanza 3 of Wild Animals I Have Known, via Landmarks

I gotta tell you, I met David when we premiered his piece and my poem at Art Night Austin E.A.S.T. tour last fall in Austin, and he and I became such great friends. I was really honored that he was excited about the poem, and he said that I felt like I understood his artwork and “got it”, so that was a really nice. I think my strength as a collaborator is having conversations with other arts and artists, so that’s why I found employing his process so engaging and interesting. Even though we weren’t having a literal conversation at that time, our arts were in conversation and not just in terms of image or subject matter but in terms of process.

EF: Have any of these multimedia projects impacted your teaching?

SSW: I do present these works in my classes, and I do have my students in my workshops write ekphrastic poems. However, I don’t at the moment have the capabilities to mentor students through this process, but I would like to in a perfect world with a lot of funding and time. I use technology in the classroom as much as I can as someone who works in a workshop-based environment. We have to do a lot of one-on-one face time, too. I do use media to teach. I use a lot of audio pieces and video pieces to talk about poems and to teach aspects of poetry as well as let the students hear people perform their work and get it in the mouth and in the body and in the ear. I don’t know if that’s part of my participation in these projects. I think that interest existed before I got involved with them. Maybe these projects are an extension are part of my interest in exploring various media, which is always an aspect of my teaching.

EF: What are you working on at the moment?

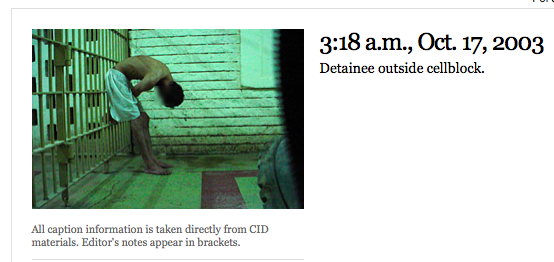

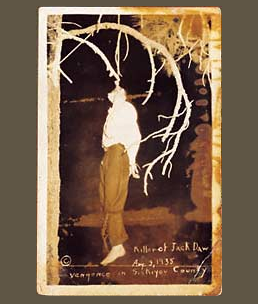

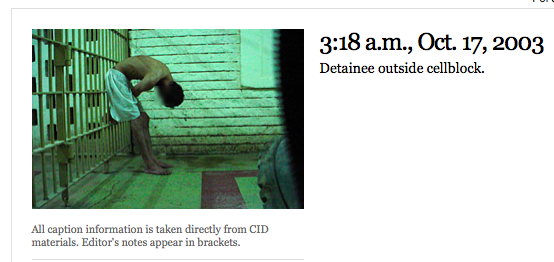

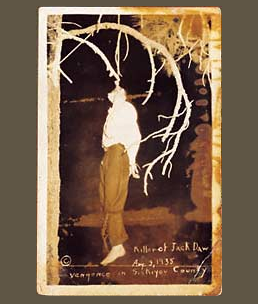

SSW: An ekphrastic project that has evolved a lot over the last few years. It’s been percolating for a while. I thought I would be writing about early photography until I saw the Abu Ghraib photographs. Contemplating those, which was really hard, made me start thinking about how we represent and experience images of torture. Also, I was looking through the book Without Sanctuary, which is of images of lynching in America for another class I was going to teach on race and gender and the image. I had experienced those images before but not put it together that I was having the same emotional and physical responses to those images when I was looking at the Abu Ghraib photographs. I think with both of those kinds of photographs, one of the hardest things to deal with is how the images are hailing me as a viewer, not just the acts themselves, which are terrible and gut wrenching. They hail all of as viewers, maybe not in the same way, but for me it calls me out and, because of my race or my nationality, constructs an identity of complicity with torture that I want to but can never absolutely reject.

Screen shot, "Standard Operating Procedure," via salon

So, for example, when I look at the Abu Ghraib photos, I feel among many other emotions, I feel this call of “You did this. You as an American did this.” I feel that the American military under the auspices of protecting people, protecting Americans engaged in these acts, so that by seeing Americans do this, I share an identity as an American, that I am implied and complicit. It’s the same thing with the lynching photographs. One of the commonly fictionalized crimes among black men who were lynched is that they were rapists or somehow a threat to white women’s sexuality, so looking at those photographs I feel that I am somehow… middling by default of how I am socially hailed in the Althusserian sense. It’s not like I condone those acts, but that’s the weird difficult space that I want to explore in my poems. What I’m currently attempting to do is represent these images in formal pairs, have a poem about the Abu Ghraib photos and then a poem about the lynching images on facing pages. By formally pairing poems about these images, I hope they can work in a lot of different ways, work as positive negative, recto verso, and all imply the photographic process itself. Though I wouldn’t call myself a New Formalist, I think as poets, we’re all formalists, some writing in received forms and some not. Otherwise, we’re prose writers.

Screen shot, "The corpse of Clyde Johnson. August 3, 1935. Yreka, California." via Without Sanctuary

On the topic of form, I think there’s an interesting resurgence of received forms, especially in African American poetry. Patricia Smith recently gave a reading at my home institution, and I asked her “What’s up with all of these received forms?” Patricia’s “Motown Crown” is amazing because she’s talking about boogying to Motown in a crown of sonnets—funk meets formal. It’s really smart. Natasha Trethewey, who has also been doing sonnet crowns, said to me that one thing that’s interesting about African American poets using those forms is that they were never meant to use those forms in the first place. So there’s always a kind of transformation of the received form simply in its contemporary use.

EF: I’m so excited to read, hear, and watch your future projects. Thanks so much for the interview.

SSW: You’re welcome.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago