Cover image of The Invention of Hugo Cabret

Children’s literature is, practically by definition, a multimedia endeavor. The beloved works of Dr. Seuss, Elsa Holmelund Minarik, Roald Dahl, Frank Baum, and countless others have a drawing at least every few pages, if not on every page. But as the audience grows older and gains reading proficiency, the pictures slowly disappear, an indication that all but the simplest of stories can be told in words alone. The multimodal aspects of children’s literature are, then, little more than a helpful scaffold to engage children while building the skills necessary for reading.

But Brian Selznick’s The Invention of Hugo Cabret (winner of the 2008 Caldecott Medal) is a book of an entirely different order. Selznick describes it as “a novel in words and pictures.” Unlike most children’s novels, in which the art simply illustrates a scene already described in words, the pencil drawings in Selznick’s novel help tell the story.

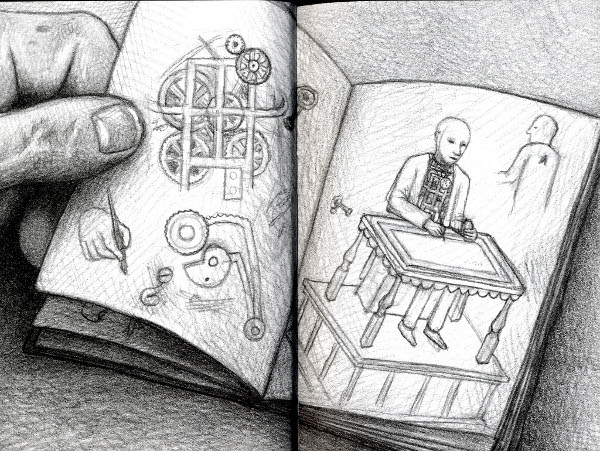

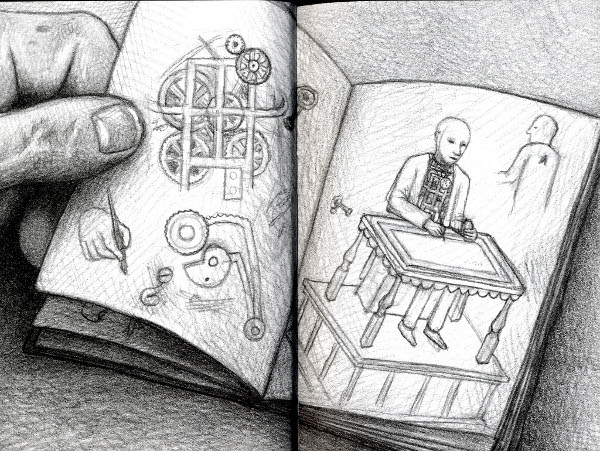

Image Credit: Screenshots from Amazon.com preview of The Invention of Hugo Cabret

The novel opens with a preface that invites the audience to close their eyes and imagine themselves in a darkened movie theater, just before the curtains separate and the projector clatters to life. Set in 1930s Paris, the book invokes silent films. The drawings throughout are cross-hatched pencil and the page borders themselves look like the cards of text that added written dialogue to early movies. It opens with an extended sequence of pictures that, from a small, distant shot of the moon, grow to fill the page while moving in ever more closely until we see, in glimpses, the principal characters. It thus makes its allegiance to cinema clear early. Yet though the form relies heavily on multiple media in a way unlike most children’s literature, the novel draws on more than just drawings and words.

A combination of detective story, historical fiction, and coming-of-age narrative, the plot revolves around recently orphaned Hugo Cabret, his repair of an automaton of mysterious provenance, and a grumpy old man who runs a toy shop in a train station.

Maillardet's automaton, which inspired Selznick

The machine, like Maillardet's above, is in the figure of a seated person, holding a pen over a desk. Hugo, who has been living in a train station since his father died in a museum fire, becomes obsessed with the idea that his father has hidden a secret message in the automaton, which it will write out once he can repair it; he believes that message, further, will save his life. Having learned the art of horology (what a great word to find in children's fiction) from his father, Hugo is especially skilled at working with gears, springs, and the other mechanisms by which the automaton functions. Once he finally repairs it (he gets parts by stealing small mechanical toys from the toy booth), the machine, rather than writing a message, draws a picture: a scene from his father’s favorite movie, A Trip to the Moon.

The drawing bears a signature: G. Méliès. Part One, in which the mystery is the automaton and Hugo’s own history (which the narrator slowly reveals to us) ends with the discovery of this output; Part Two follows up by trying to discover why the old toy maker knows about the automaton and reacts so emotionally when he finds that Hugo carries a notebook with drawings of it. As we learn, Papa Georges, as his god-daughter calls him, is Georges Méliès, one of the early innovators of cinema, the automaton's inventor, a magician, and, by those who remember him, believed dead. Through Hugo’s efforts, the French Film Academy uncovers many of his films, all of which had been thought lost, and reintroduces Méliès and his fantasy-filled, revolutionary movies to the world, thereby giving him back his purpose, without which he was, in Hugo’s mind, like a broken machine. Fittingly, movie stills and sketches from the real works by Méliès also intersperse the pages, layering yet another visual medium onto the narrative.

A still from A Trip to the Moon by Georges Méliès

Hugo often thinks of his own mind as a machine of gears and springs. He sees the world as one large machine in which everything and everyone has a function. He has nightmares about broken clocks. He carries gears in his pockets. Machinery ticks through the novel, texturing the illustrations and the imagery, explaining Hugo’s mind, and linking the different parts of the novel. At the conclusion, we discover that, rather than an author, the book was produced by a fantastically complicated automaton that drew all the pictures and wrote all the words, a machine constructed by (who else?) the now adult Hugo Cabret, who has taken the name Professor Alcofrisbas, a recurrent character in Méliès’s films. Machines become, in other words, another medium through which the novel tells its story.

In weaving allusions to machines throughout the work and then concluding with the fantasy of a novel-producing machine, The Invention of Hugo Cabret requires us to consider not only words and pictures, but also the physical machinery of book production and the author as a machine. Recalling the drawing automaton Hugo repairs, the fantastic novel-writing machine inserts itself unavoidably into our visual imagination. Drawings, movies, and clockwork machines are all integral elements of the novel, taking it far beyond picture books. The cinematic aspects join the machinery of creation to create a work that is uniquely beautiful, densely textured, and experimental: traits rarely seen in literature for any age group.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago