How does the space in which protest art appears affect the ways in which people respond to it? Or, even, if they see it as a protest at all?

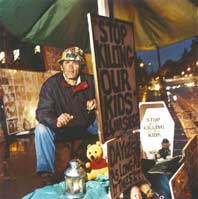

In my class the other day, we talked about protest art. Among other things (Shepard Fairey), we looked at anti-war peace protester Brian Haw. Haw has lived in a peace camp in Parliament Square in Britain since June 2, 2001, remaining at the site full time, leaving only for court appearances.

Over time he amassed a large collection of signage (over 600 signs) that took up considerable space in the area.  However, after continuous struggles with the police over his right to be there (and their attempts to remove him), Haw finally applied for a permit and was approved, but only under the condition that his demonstration site did not exceed three meters in diameter.

However, after continuous struggles with the police over his right to be there (and their attempts to remove him), Haw finally applied for a permit and was approved, but only under the condition that his demonstration site did not exceed three meters in diameter.

But the story gets better. Mark Wallinger recreated Haws' signs in an exhibit called State Britain. The description on the Tate Gallery website reads:

Mark Wallinger has recreated peace campaigner Brian Haw’s Parliament Square protest for a dramatic new installation at Tate Britain. Running along the full length of the Duveen Galleries, State Britain consists of a meticulous reconstruction of over 600 weather-beaten banners, photographs, peace flags and messages from well-wishers that have been amassed by Haw over the past five years.

Faithful in every detail, each section of Brian Haw’s peace camp from the makeshift tarpaulin shelter and tea-making area to the profusion of hand-painted placards and teddy bears wearing peace-slogan t-shirts has been painstakingly sourced and replicated for the display.

While the Tate website argues that "bringing a reconstruction of Haw’s protest before curtailment back into the public domain [...] raises challenging questions about issues of freedom of expression and the erosion of civil liberties in Britain today," I would argue that thinking about both of these visual collections raises questions about efficacy and intent. Do those who see this exhibit in the museum consider this a protest? Or do they view it more as something removed? My students argued for the latter concept, and I am tempted to agree with them. But, something should be said about Wallinger's project's ability to "save" Haw's artificats, which otherwise would be gone from the public eye. But can the exhibit still do the work that these signs did at Haw's camp?

However, after continuous struggles with the police over his right to be there (and their attempts to remove him), Haw finally applied for a permit and was approved, but only under the condition that his demonstration site did not exceed three meters in diameter.

However, after continuous struggles with the police over his right to be there (and their attempts to remove him), Haw finally applied for a permit and was approved, but only under the condition that his demonstration site did not exceed three meters in diameter.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago