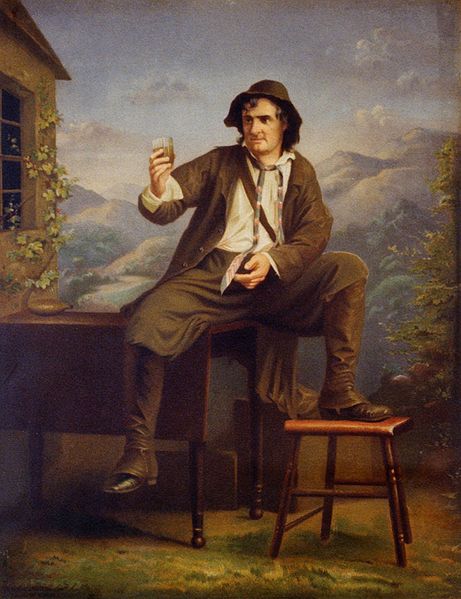

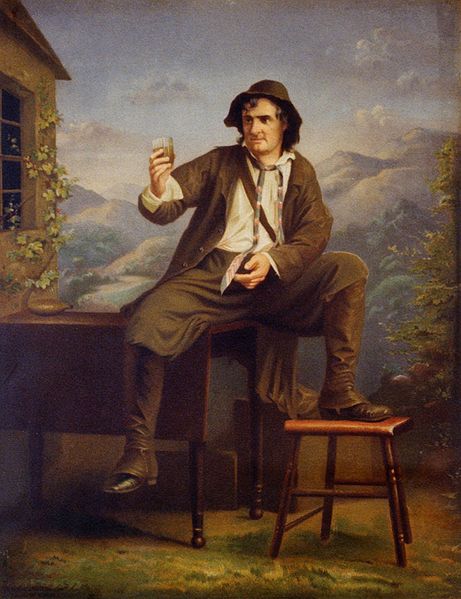

Joseph Jefferson as Young Rip Van Winkle Image Source: Wikipedia

In my last post, I began telling the story of how “Rip Van Winkle” came to be converted to film. The story is fraught with all of the workplace drama and power plays that one might expect from a nascent Hollywood industry. It’s a tale of stolen ideas, patents, and lawsuits, that led to an eventual motion picture industry monopoly. As I mentioned in my last post, most scholars credit Thomas Edison’s assistant, Laurie Dickson, with the creation of the Kinetoscope, an invention very similar to the Mutoscope on which audiences would have viewed Rip Van Winkle. The invention was essentially a peephole in a tall rectangular box with film running between two spools. Around the time of the invention’s 1892 patent, however, the relationship became rocky.

Although Mutoscopes and Kinetoscopes were very profitable, a projector which could play to a large audience would bring in higher revenue. In 1895, inventor Woodville Latham, with his sons, had created a projector called the Eidoloscope. Edison’s main assistant, Dickson, out of a seemingly genuine interest and earnest love of inventing, wittingly or unwittingly broke his contract by helping the Latham family in inventing this new projection device. Displeased that Dickson had shared his great ideas, leading to the benefit of his competitors, Edison fired him. Dickson ended up staying with the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company – the group which is credited with the making of Rip Van Winkle.[1]Curiously, or perhaps understandably, the film is often listed as a product of the more popular Edison Company, and this is because of a monopoly that Edison forced into being.

In spite of Dickson’s perceived mutiny, Edison found ways for his company to prosper. At this time, many films were “duped” or copied from other films, and so Edison Studios began to trademark their original actuality films. This, however, led to Edison constantly suing other movie studios (Lubin, Vitagraph, Essanay) over patent infringements. To try to put a stop to these costly lawsuits, the Edison Company formed the Edison Association of Licensees in 1908 which set down grounds rules over film release dates for companies. Biograph studios (the group which Stephen Johnson, Patrick Loughney and Kenneth McGowan cite as the producer of Rip Van Winkle) retaliated and formed their own group. Eventually both groups merged into the Motion Pictures Patents Company in 1908. This eventually became known as “the Trust” – a motion picture monopoly. Hence, Rip Van Winkle is probably credited to Edison studios because that was the largest company, but not necessarily the studio which produced it, even if Edison may have owned the rights to it.

The Film

The actor we see in the Mutoscope film, Rip Van Winkle, is Joseph Jefferson. Jefferson’s career is an interesting one for understanding the contiguous flow of drama to cinema at this time. He actually first produced a version of “Rip Van Winkle” for the stage which was co-written with British melodrama writer Dion Boucicault. Together they changed the plot of the short story almost entirely (which I’ll discuss more in my next post). After the opening of the play in London, audiences were clearly enamored. It was, in fact, so popular that Jefferson toured with it in the U.S. for the rest of his life (Johnson 4)[2]

Further capitalizing on his success, towards the end of his career, in 1895, Jefferson published a book version of the play which contained “stage directions, complete dialogue, plus photographic and other illustrations documenting costume, make-up, scenery and other production elements” (Loughney 279). Perhaps ever thinking of new ways he could self-promote, Jefferson had been an early investor in the American Mutoscope and Biograph Company (Loughney 278). It’s easy to see how an actor of the stage would want to invest, and perhaps get his foot in the door to be involved, in the nascent medium of film. For Laurie Dickson, who had a lifelong goal of making a film based off of an “entire play” his partnership with AM & B and their connection to Jefferson must have seemed serendipitous.

Dickson finally arranged with Jefferson to have the play turned into a short film by Mutoscope ‘on location’ near Jefferson’s rural country home. As critics like Stephen Johnson have pointed out, the film is valuable because “It provides us with insight into Jefferson’s unique style of acting.” While scholars can read stage directions and reviews, or examine photos, so much more is revealed through observing the living motions of the actor.

Adding to confusion over who produced the film, Johnson adds that “Jefferson’s production was popular enough that, in addition to the film, he was asked to recite selections for Edison’s sound-recording cylinders.” Though the Youtube video is labeled ‘Edison,’ all sources consulted say AM & B produced Rip Van Winkle. Moreover, the Library of Congress’ site doesn’t have Rip listed among their films, though their list is not perfect either. Perhaps Johnson is referring to Edison cylinders as a brand, more than to name a company affiliation (11).

While the points of origin for the film are somewhat tenuous to track down, the content of the play itself is not. Stay tuned for my next post in which I’ll offer my own analysis of how these changes relate to the play version of the story; how the play varied from the film; how these scene selections altered the storyline; and a suggestion that “Rip Van Winkle” is a story particularly well-suited for film.

[1] Edison eventually bought the rights from an inventor to a projector which he named the Projecting Kinetoscope.

[2] Johnson, Stephen. “Joseph Jefferson's ‘Rip Van Winkle’”The Drama Review. 26.1, Historical Performance Issue (Spring, 1982): 3-20. Web. Feb 9, 2013.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago