Image source: Dissolve.com

Branding and corporate marketing can be bizarre. Sure, there are the big brands, the Disney’s or Budweisers or Coca-Colas, whose very names evoke our day-to-day experience of the products they market. For those of us who like to think about how visual rhetoric interacts with pop culture, these iconic multinationals can provide endless streams of data. Watching how such companies endlessly race to reflect or mold global and American cultures so as to increase visibility may sometimes be a depressing project, but it is always fascinating. But what about the guys who we don’t interact with on a daily basis? I’ve never had an opportunity to purchase anything advertising itself as a British Petroleum product, yet I’ve been saturated with billboards and advertisements seeking to win my good-will for the company. Similarly, I grew up watching striking ad after striking ad for the chemical company BASF, even though their tagline explicitly reminded me that “we don’t make a lot of the products you buy.” I will probably never make any purchasing decision that affects BASF’s bottom-line, yet they seem to have been quite passionate about convincing me that “we make a lot of the products you buy better.”

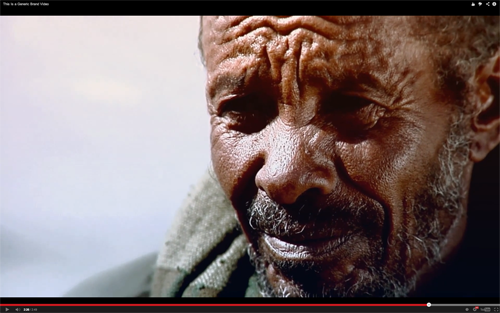

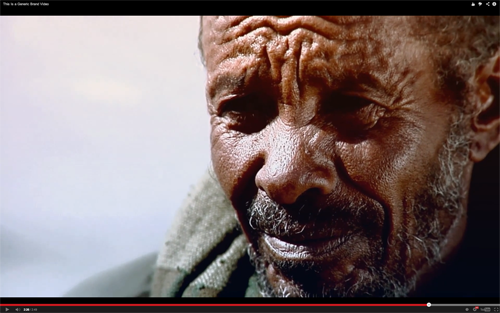

Companies whose work only indirectly affect our lives find themselves in a rather comical rhetorical situation. How can you attract a following as large as possible, made up of people who don’t know what you do, without offending anyone in the process? The answer, at least according to Kendra Eash’s satirical poem, is to throw a bunch of incoherent yet iconic images together, targeting as many different audiences as possible, while always remembering the importance of committing to nothing. “We think first,” Eash’s poem begins, “of vague words that are synonyms for progress / And pair them with footage of a high-speed train.” Her description of the video passes through a sea of carefully calculated images and ends with inanity. “Did we put a baby in here?” she asks. “What about an ethinic old man whose wrinkled smile represents / the happiness and wisdom of the poor? / Yep.” If a corporation has nothing to sell you directly, there’s always the old standby: instead of selling a product, sell people back their own cliches.

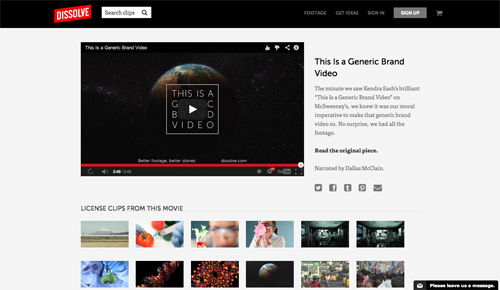

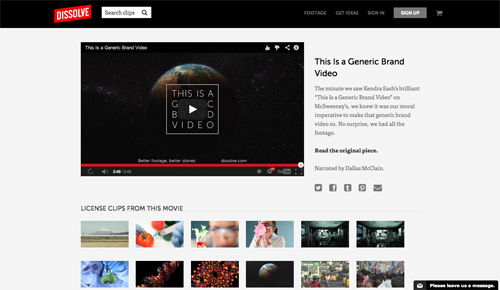

The poem took an interesting turn when read by someone at Dissolve, a company that provides stock footage. Since Dissolve already had vivid film clips to match each of Eash’s described scenes, they stitched them together to create the ultimate, and ultimately generic, brand video. It’s worth a watch. It maps, in vivid detail, the moral and aesthetic universe advertisers imagine when trying to attract mass-media viewers to their cause.

Image source: Dissolve.com

The website upon which Dissolve posted the piece adds two layers of irony to the whole experience. On the right, the makers praise Eash’s article and inform the reader that “we knew it was our moral imperative to make that generic brand video so. No surprise, we had all the footage.” Why Dissolve might feel a Categorical Imperative to mock one of its prime markets is, of course, left humorously vague. Less vague, of course, is the icons that take up the bottom of the screen: every clip from the trailer, conveniently laid out in rows, waiting for the filmmaker willing to invest $50 per short HD clip of emotional manipulation.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago