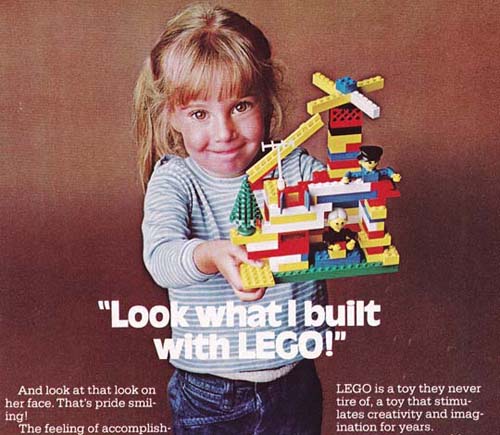

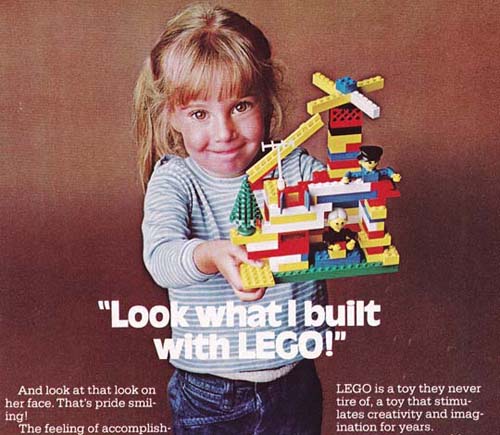

1978 LEGOS Ad. "a toy that stimulates creativity and imagination for years." Source: Ourlifeintoronto.com

Sometimes, it’s hard to separate a film from the circumstances in which you watch it. In my case, I saw it as a father of a 1-year-old, sitting at the Alamo Drafthouse, following a preshow that included one of the early advertisements for LEGOs, then a European import newly reaching America’s shores. On multiple levels, I kept thinking of how much The LEGO Movie might represent a low point in both how we imagine children’s entertainment, and how we imagine children themselves.

2014 The Lego Movie: Explosions, Lens Flares, and Desperate Running. Source: IMDB.com

That isn’t to say that The LEGO Movie isn’t interesting. In fact, one of the things that makes it most noteworthy is that the film actually tries to say something. Rather than just attempting to sell LEGO’s, the show presents a dialectic between two conflicting (yet enthusiastically childlike) phrases: “everything is awesome” and “you are special.” “Awesomeness,” in this movie, is tied to conformity, but also cooperation; as the opening song has it, “everything is cool when you’re part of a team.” “Specialness,” on the other hand, is explicitly presented as the movie’s central theme. As multiple characters put it throughout the film, “you are the most talented, the most interesting, and most extraordinary person in the universe. And you are capable of amazing things.”

1955 ad for Lego System Image credit: Youtube.com

Perhaps it’s hard not to feel special when playing with LEGO’s; where the original advertisement for Lego Universal System emphasized the ability to build individual objects, LEGO sets do give children the sense of having godlike powers, of creating a world that answers to them and them alone. At its best, The LEGO Movie's visuals echo the anarchic pleasure of building with LEGO blocks, celebrating ugly juxtapositions (“special!”) rather than frozen perfection (instruction-following “awesome”). When the movie does encourage such anarchic construction, it evokes the childlike pleasures of a LEGO's aesthetic: conflicting colors jarred together in defiance of mature adult tastes.

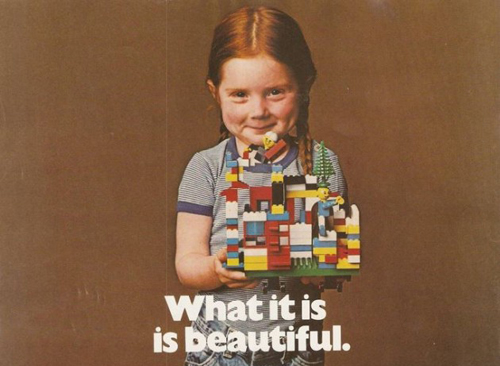

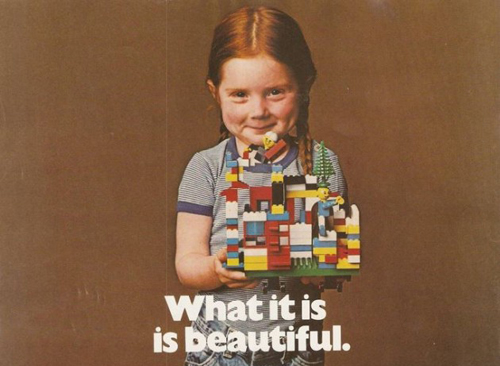

1981: Yet Another LEGO builder who needs no instruction manual. Image source: womenyoushouldknow.net

However, I was more disturbed by what The LEGO Movie seems to think it means to be an individual, or "special." We start with the same character as almost every Hollywood epic: a white, normal-looking straight man who just can’t fit in. The film’s story, then, runs down a checklist of “epic movie conventions” so hackneyed I can recite them in my sleep. We have

1) The aforementioned white protagonist, who

The middle-class looking nerdy boy is the first to train dragons! Who would've thought? Image source: imdb.com

2) meets the immaculate, superlatively competent girl who falls inexplicably in love with him,

Even the most creative of films rely on old stereotypes. Image source: imdb.com

2) finds himself among a group of people who seem to be pretty special themselves, but ultimately will give heartfelt speeches about how much better he is than them,

He may be foreign to their culture and have little understanding of their situation, but all the Na'vi look to the human Jake Sully for guidance. Image source: avatarmovie.com

3) and of course is aided by the death of the Magical Negro, played by Morgan Freeman, the most magical and godlike of all black side characters to throw himself beneath a bus for his white heroes.

Guess which of these guys gets to die not once but twice so that his fellow ex-CIA killers may live and have a sequel? Image source: comingsoon.net

4) Finally, as seems to be the case in all kids movies these days, the hero slaughters a horde or two of mundane, drab-looking folk simply to prove his own awesomeness; no one cares about how many policemen get lasered, drowned, crushed, or otherwise slaughtered in The LEGO Movie.

Gandalf: True courage is found in knowing not when to take a life, but when to spare one. Bilbo: Did you really just say that with a straight face? Have you even read the script for this movie? Image source: lotr.wikia.com

Sure, some of the details do satirize the film’s color-in-the-lines Epic Movie construction. It’s nice to see a woman reject Batman as a boyfriend, for instance. (Batman is the boyfriend that no one deserves, and no one needs.) Freeman’s joke at the end does give him access to the most whitest of white cultural positions, the hipster. Yet why does the movie’s only female lead continue to be a cookie-cutter idealization of our current domestic ideal (the badass competent human being who can provide for our hero’s security in an economically-fragile world, but also the swoony fem who needs to be attached to the main character, and serves as his ultimate prize)? Why is there no living black character by the end of the movie?

Each of the stereotypes that The LEGO Movie uses is, perhaps, useful from both a marketing and a creative standpoint, yet The LEGO Movie's insistance that children's imagination is made up of nothing but these well-trod cliches is disturbing. Real children's imaginations tend to be discontinuous. jarring, confounding to adult sensibilities. Children are clever at picking up on our clches and narratives (sometimes when we don't want them to), but they are also capable of combining bits and pieces of stories they've heard into new wholes with all the enthusiasm of a young girl slamming together discordant blocks in hopes of creating a LEGO masterpiece. But of course, such free play has nothing to do with the mechanical repitition of Hollywood formulae running in our theaters. Nor is frewheeling creativity something that recent LEGO marketing wants to encourage, especially for girls.

Recent LEGO models targeted to a female consumer-base are specifically designed not to interact with normal Lego sets, clearly implying that the pieces featured in The LEGO Movie are off limits to girls. As the very girl featured in the 1981 ad points out, “in 1981, LEGOs were simple and gender-neutral, and the creativity of the child produced the message. In 2014, it’s the reverse: the toy delivers a message to the child, and the message is weirdly about gender.” Of course, there are financial incentives for doing so; not only are parents unable to re-use LEGOS for children of different genders, but girls and boys are each encouraged to buy the latest pre-made sets. LEGOs becomes less and less about creativity and exploration, and more and more about following the narrative laid down by Hollywood scriptwriters and advertisment execs.

I left The LEGO Movie humming “Everything is Awesome,” and it’s been the background to much of my headspace for the past week or so. But I also left wondering who it is that we allow to be seen as special in our society, and how we encourage our kids to think about the idea of “specialness.” I am also confused by how very eagerly critics seem to take the movie at its face value, or even praise it for demonstrating “how the weight of ‘adult concerns’ conspires to kill the child in all of us." But the thing is, children don't tell stories as uninspired and predictable as that found in The LEGO Movie--unless, of course, they receive enough signals that these are the only stories worth considering. If LEGO was once "a toy that stimulates creativity and imagination for years," The LEGO Movie seems to be just the opposite; a love-song to the death of creativity wrapped in clever-yet-superficial satire and a thoroughly disingenuous claim that "everyone is special."

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago