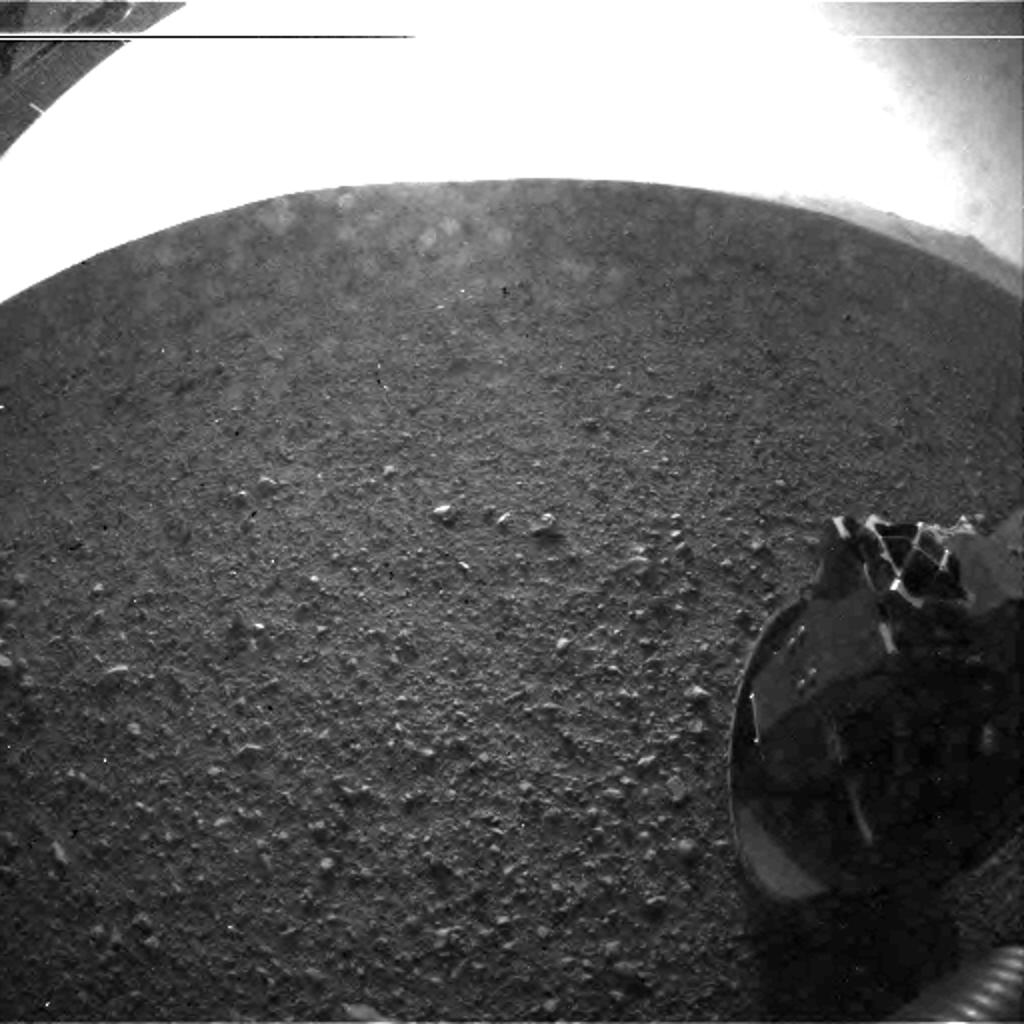

Image source: CNN.com

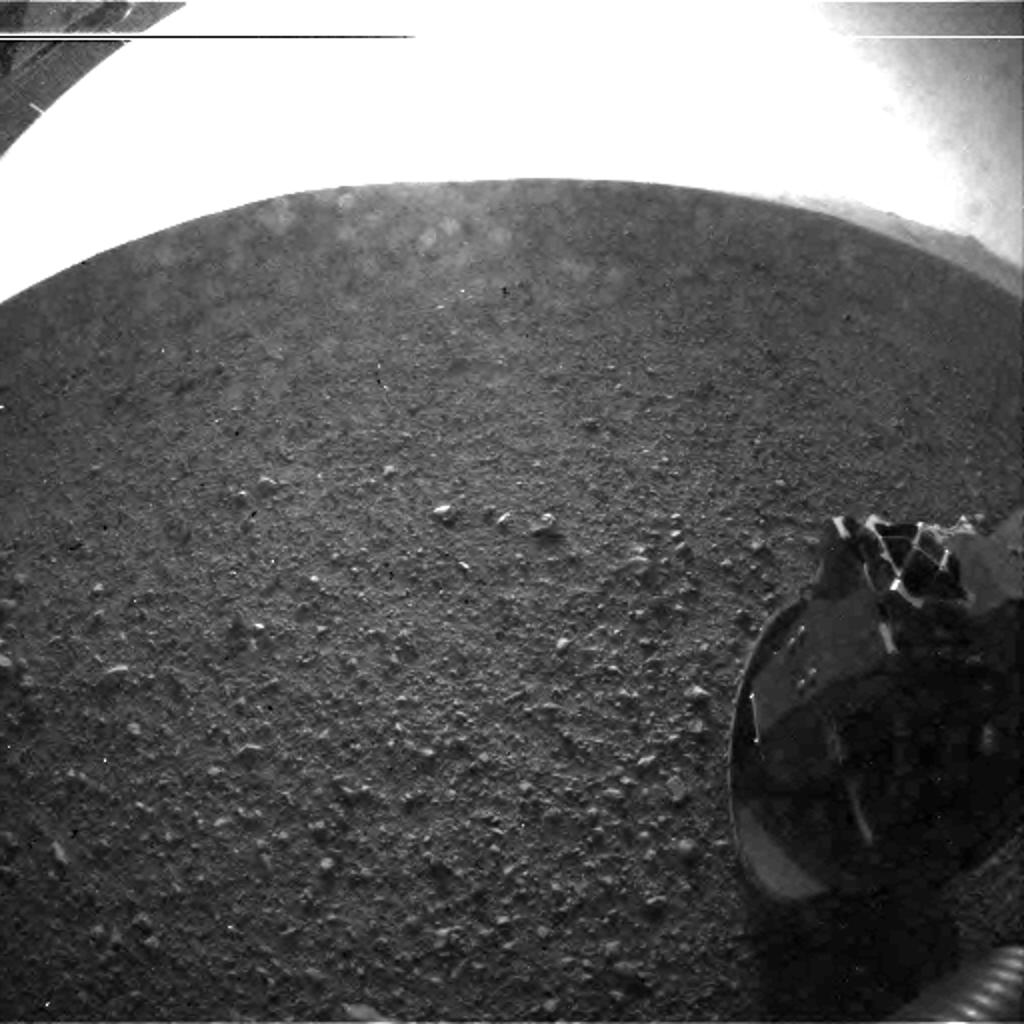

Yesterday, an image tweeted by the Mars Curiosity Rover with the message “Look back in Wonder . . . My 1st Picture of Earth from the Surface of Mars” proliferated on the internet. As I stared into the screen, primed by half-a-century’s worth of cultural reference points, the oft-repeated excerpt from Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space (1997) came to mind. Looking at the latest Mars Curiosity Rover images, I couldn’t help but think about how I navigate my connection to Earth through a series of more iconic images of space, and the things which have been said about those images. In this post, I’d like to briefly walk through some of the other iconic photos of Earth that inform our present viewing experience.

Image credit: Nasa.gov Mars Curiosity Rover (left), Wikipedia.org first image from space (right)

The first photo of Earth from space was actually taken in 1946 from a rocket 65 miles above the New Mexican desert, but it isn’t one which inform's how most view the Earth from space – even today few people know that the image exists. Like the Mars Curiosity Rover, the sub-orbital V-2 Rocket which captured the first image of Earth was also unmanned, at the forefront of a very new technology, and thus, this first image of Earth is of a low aesthetic quality. It’s worth acknowledging that in time, a Mars Rover may reveal a new, more paradigm-shifting image. After all, a little over two decades after the 1946 missile’s grainy photo from space, the world first saw the universally celebrated Earthrise, an image taken from the moon by William Anders in 1968 during the Apollog 8 mission. Though not the first, Earthrise, has been described as “the most influential environmental photograph ever taken” -- any new visions about space photography, any cultural ideas, hearken back to what was said about this photo.

Image credit: Earthise (1968) wikipedia.org

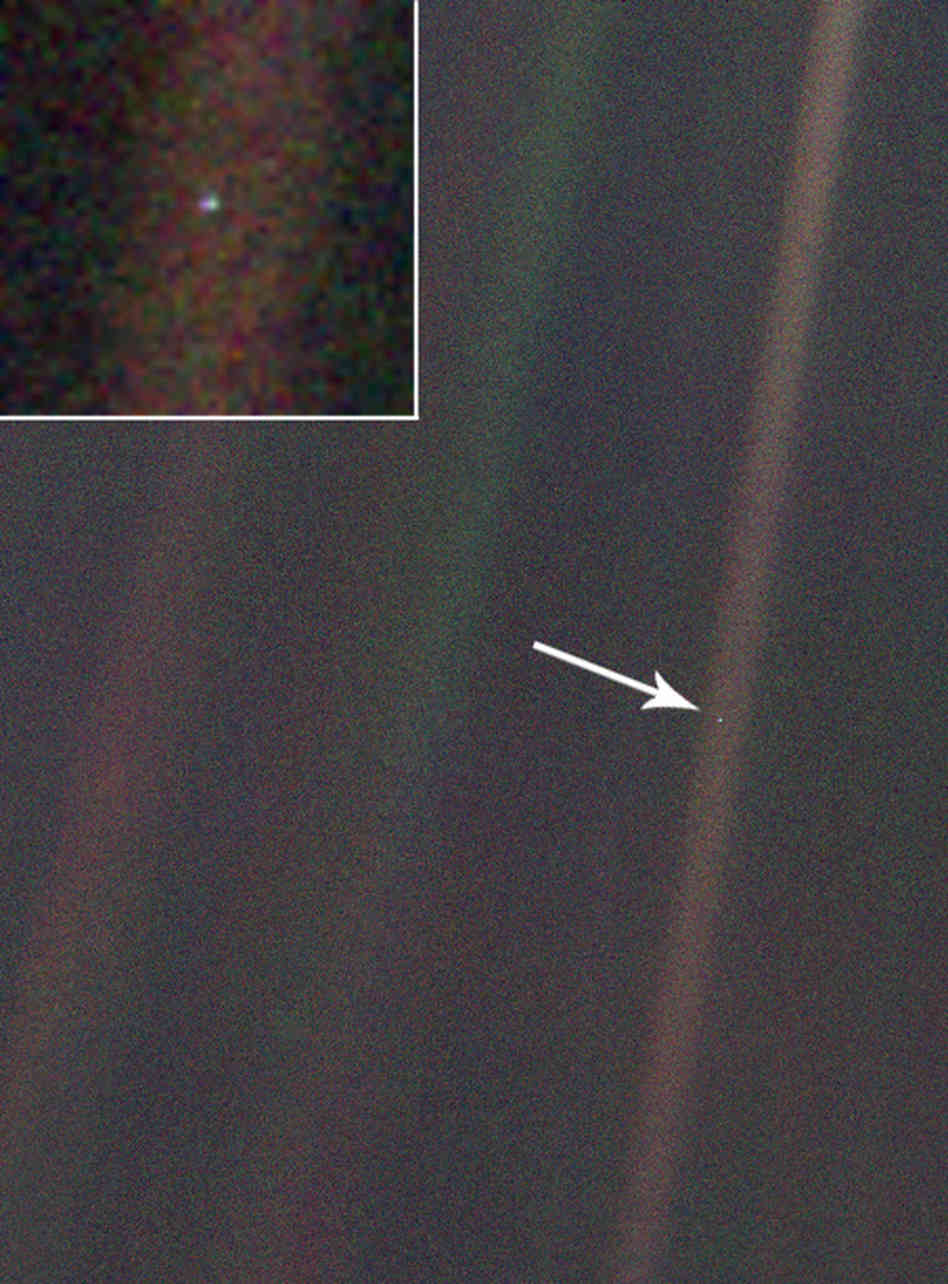

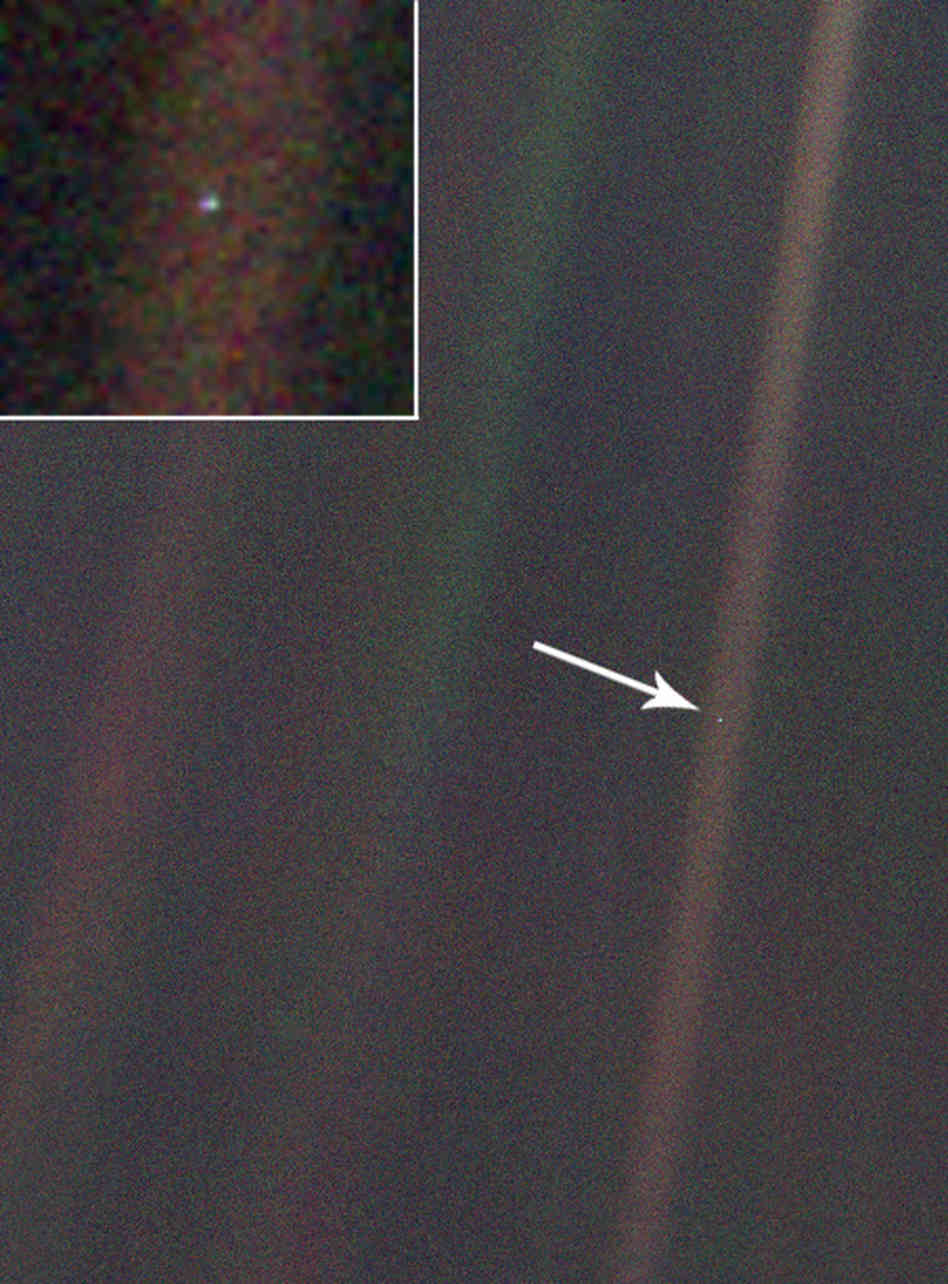

NASA has referred to this new image of Earth taken from Mars as an “evening star.” When writing about the legacy of this image, The Atlantic’s Associate Editor, Robinson Meyer, notes that it follows in the legacy of The Blue Marble (1972), and Pale Blue Dot (1990). According to Meyer, in the 1960s, images of space “were something activists yearned for,” citing The Whole Earth Catalog whose editors called for a cohesive image of the planet, believing that merely viewing such an image could bring about humanitarian and environmental aims. Today, some might think of this view of space as part of a naïve, 1960s essentialist vision of activism. While studies of essentialism and activism in the academy are a well-traversed area of thought, this view of essentialism is still a status quo lens for most of the world outside academe and activist circles, and that tends to come out during widespread public conversations about space like the ones we’re having this week. The video "Some Strange Things are happening to Astronauts Returning to Earth" from the popular “clickbait” site, Upworthy, serves as an example of the contemporary popularity of these ideas. The message is that viewing Earth can save us, if we only let it, etc. I don’t mean to dismiss the message, only to point out that it’s interesting how a vestige of cultural and political formations of the 1960s has survived with little mutation. It’s an example which highlights the way past frames for viewing the Earth from space continue to persistently inflect our thinking about new images from the Curiosity Mars Rover.

Image credit: Pale Blue Dot (1990) NPR.org

Like “evening star,” Pale Blue Dot was also grainy, and also taken by an unmanned craft: the Voyger 1 space probe. Just as the Mars Curiosity Rover tweeted “Look back in wonder . . .My 1st Picture of the Earth” the Voyager 1 also caught Earth after a command was sent to “turn the camera” back towards Earth. What’s interesting about Pale Blue Dot is that it is best known, not for the image itself, but for the pathos of what public intellectual Carl Sagan wrote about it. A Youtube search for Pale Blue Dot yields countless montages of iconic photos, movie clips, digitally enhanced or fabricated images of space, and even, Earthrise. These mainly iconic images and film clips in countless Youtube homages to Sagan highlight that Pale Blue Dot carries a sort of 1960s mantle. Or perhaps it’s that the general public is so influenced by Earthrise that we can’t see Pale Blue Dot without a hint of late 60’s essentialism. That Sagan’s words outweigh the actual image of Pale Blue Dot highlights that these photos of space often galvanize paradigm shifts in culture, which are registered in books, films, movies, and today, online.

Carl Sagan was 34 when Earthrise first came out, and so understandably, his ecology is a “bright” one, as eco-critics would put it. His words are inflected with what is often read as the “naïve optimism” characterized by the makers of the Whole Earth Catalog in their call for a “unifying” image. This was not entirely in spirit with the 1990s. The impact of Earthrise was so particularly strong, that it is difficult for anyone, myself included, to look at “evening star” without thinking, “Pale Blue Dot,” “Earthrise,” etc.

These new images of Mars beg the question, what will the next generation have to say about the Earth from space? From the Whole Earth Catalog, to Carl Sagan, we’ve grown to expect defining speeches and commentary to accompany these images. Today, as anyone's tweets in response to a rover’s tweets can, and do, go viral, it becomes harder to track what will be logged in our memories as a “defining” cultural frame for these photos. Neil de Grasse Tyson, protégé of Carl Sagan, is remaking the popular series Cosmos for new audiences, which is slated to come out later this year. Whether it will present a dark or bright ecology; whether it will carry the banner of Sagan’s eternal optimism, or say something entirely new, I ‘m curious to know.

In my next post I’ll talk more about the pathologizing of earth from space in our contemporary moment, from the tragic demise of the Yùtù (“Jade Rabbit”) rover, to the more recent Mars Curiosity Rover’s hypermediated tweets.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago