Image Credit: Huffington Post

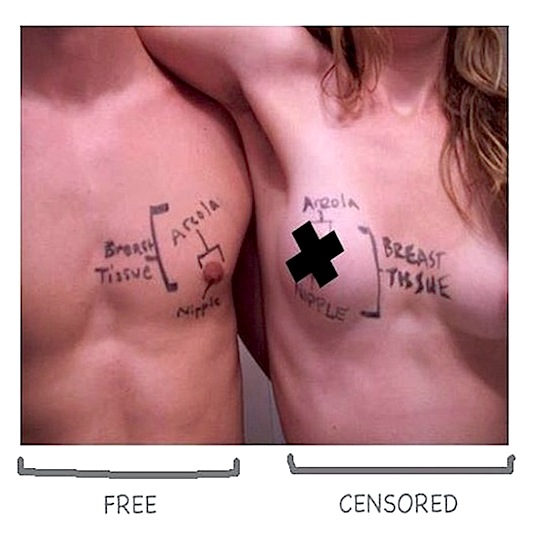

In 2005, the artist Jill Coccaro was arrested in New York for exposing her breasts in public. In 2012, Jessica Krisgsman was arrested in New York for topless sunbathing in a park. In 1992, New York courts ruled that banning female toplessness in public violated equal protection clauses and, as a result, it became legal for women to bare their breasts in the state. Apparently, the memo about the legal rights of topless women is still in circulation. Social activist and actress Lina Esco is slated to release her film Free the Nipple in June of this year. The movie will explore American cultural discomfort with the alleged “lewdness” and “indecency” of women going topless. Esco has written several fantastic Huffington Post progress reportsfor her project, chronicling the struggles she has faced in the composition of her movie , struggles like police involvement during filming and battling social media networks that have banned her accounts for putting up pictures of partially nude women. Esco also beautifully captures her own bafflement about what she sees as bizarre standards of American morality, asking why “acts of baroque violence, killing, brutalization and death are infinitely more tolerated by the FCC and the MPAA, who regulate all films and TV shows in the US.” Shooting a film about breasts has proven more difficult that shooting a film about, well, shooting. The Free the Nipple campaign has attracted the attention, and largely benefited from the patronage, of celebrities like Miley Cyrus, whose December tweet on New York toplessness laws generated quite a bit of internet buzz. Her tweet was accompanied by a photo of her flashing the camera, breasts colorfully covered with photoshopped hearts.

So what are the stakes of normalizing the public exposure of female breasts? Some activists identify the controversy as a fight for equal rights. Since men are not subject to regulation or judgment for being topless, women shouldn't be, either. Many affirm that prejudice against women willing to bare their breasts in public is an archaic, leftover standard from puritanism in America's background. According to this view, American culture has decided that female b reasts are inherently sexual in nature and that no situation exists that could strip them of their “natural” sensuality. Those fighting to normalize the sight of female breasts argue that th e notion of inherent sensuality , based in religion for some, evolutionary determinism for others, and collective ideas of common decency for still more, objectifies and hypersexualizes the female body. For example, if all I want to do is sunbath, maybe catch up on my reading in the park, how can I be blamed for inflaming the lusts of those around me? Only if female breasts are innately sexual.

In a case where one side of the argument is primarily concerned with the way women's behavior impacts men, in this particular case through unsought arousal and possibly even moral contamination, it's pretty safe to say that I'll be found firmly in the opposing camp, setting up a tent and looking for a clean water supply because I'm prepared for a long stay . Is there any possible way, though, to argue that normalizing toplessness somehow doesn't serve the best interests of women? It seems to depend on whether or not we take certain social truths for granted. Emily Yoffe caught a lot of flak for writing about the relationship between binge drinking and sexual assault. Yoffe's article, in an attempt to be practical and helpful, encourages women to avoid heavy drinking at parties so that they will not be targets of sexual predators. Other feminists responded negatively to Yoffe's opinion piece, arguing that her “helpful advice” was just another form of victim blame. Women, they assert, should be able to drink without fearing assault . Louise Pennington responded to Yoffe with an article of her own, snappily titled “The Best Rape Prevention: Tell Men to Stop Raping.”If we assume, with Yoffe, that sexual predation is a simple, tragically unfortunate fact of life, then topless women might be making themselves vulnerable to objectification, even physical danger. It would be a sad truth: our society is incapable of responsibly handling the public liberation of the female body. Contra a Yoffe-like position, opponents could argue that the normalization and legalization of toplessness would serve to deconstruct our cultural belief that breasts are inherently sexual, thereby demystifying the female body and helping to decrease objectification. I find myself a firm supporter of the latter idea, but I continue to be impressed with the varied, arguably feminist responses to what can and can't/ should and shouldn't be seen of the female body.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago