Image credit: The Guardian

The first song composed for (but ultimately cut from) the recent Disney blockbuster Frozen explicitly engages with Disney's presentation of female characters. In the song, entitled "We Know Better," young princesses Elsa and Anna lay out a laundry list of objections to the traditional idea of a "Disney Princess." The film's two heroes refuse to be the sort of princess who "always knows her place," insist that a real princess “laughs and snorts milk out her nose," and maintain their right to mention “underwear.” Though whimsical, the film sets out its heroines' priorities: the only things they take seriously are their sisterly friendship and the political demands of ruling the realm. In climactic two-part harmony, the girls promise to "take care of our people and they will love / Me and you." If films like Tangled and Brave taught Disney that their princesses can (quite profitably) take center stage without dressing up as boys, Frozen insists that its female leads will be more concerned with national policy than with the clothes they wear.

The film's feminist aims were reflected in early reviews. NPR discussed the film's hit single, and the message of empowerment that many tweens heard in its lyrics. Social media exploded with a list of "7 Moments that Made Frozen the Most Progressive Disney Movie Ever." On the other hand, Frozen came under fire for perpetuating some of the worst tropes of the very "Disney Princess" genre it mocks. From critiques of Elsa's embodiment of Disney's Madonna-whore dichotomy to concern over the ridiculous gender dimorphism of its CGI character-models, the movie collected criticism as well as praise from feminists. Frozen was often compared unfavorably to Lilo & Stitch, a movie with its own fascinating treatment of social narratives.

In this post, however, I'm not particularly interested in praising or condemning Frozen so much as in understanding how it works. In particular, I want to draw attention to a visual contradiction that I see energizing much of Frozen. On the one hand, the the film claims to be a reversal of what we expect from a Disney film. On the other hand, in its meticulous computer animation actually displays a deep reliance on the sorts of traditional, emotional-powerful images created by Disney and other culture-makers over the years.

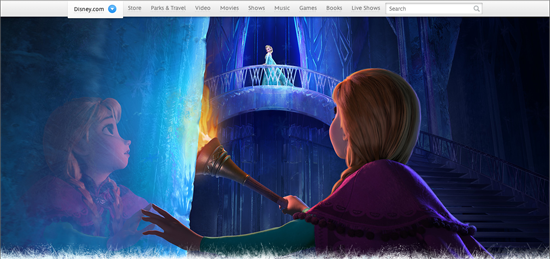

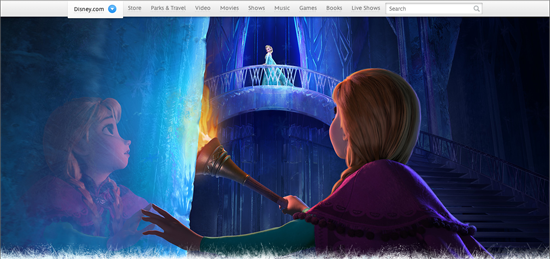

Take, for instance, the following freeze-frame, an image featured in various promotional materials, including (as seen below) Disney.com's website for the film:

Image credit: Disney.com

This image is particularly powerful because, in its essence, we have already seen it a million times in previous fantasy films and cartoons (though never, perhaps, executed with such icy beauty or complexity.) A young protagonist gazes upon an exotic, striking location, while the viewer's gaze is drawn along the explorer's eyeline through careful image composition. At the top of the image is a distant, female beauty, more of an icon than a person; Elsa's face is an indistinguishable blur, looking over her elegantly-clad shoulder as her dress swirls about her.

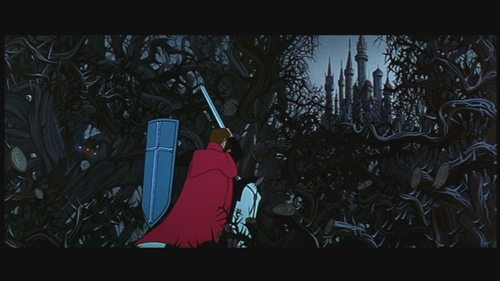

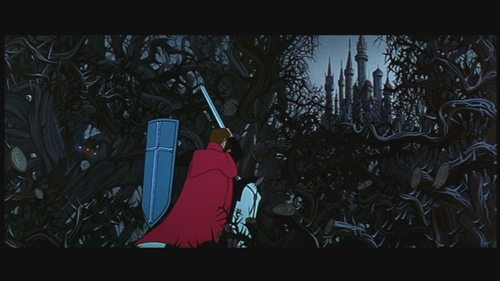

Such an image announces its continuity with previous riffs on the same motif, such as the scene where Prince Phillip hacks his way towards his future wife's magical castle in Sleeping Beauty, or the scene where Alladin's titular hero looks out at the city of Agrabah while dreaming of the life lead by its princess, Jasmine. Indeed, the parallels from the former seem particularly striking. Frozen is the first "ultra-widescreen" Disney fairytale since Sleeping Beauty, and Eyvind Earle's detailed, decorative background work on Sleeping Beauty stands as a predecessor for the elaborately ornate (yet often-threatening) nature of Frozen's arctic scenes.

The two protagonists' red, flowing capes are also suspiciously similar. Image credit: Evensi.com

If Frozen shares much in common with Sleeping Beauty, it also follows T.S. Eliot's dictum that "immature poets imitate; mature poets steal." The most obvious shift is one in the characters' gender and motivation. Where Prince Phillip seeks merely to rescue his love and obtain the obligatory "happy ever after" of marriage, Anna's goals are doubled--even doubled against each other. She seeks to be reunited with her sister and thereby restore their family bond, but she also wants to save the realm from her sister's magic, a political task that places the two of them in a (potentially) adversarial relationship. Within this freeze-frame, then, it is fitting that Anna herself is duplicated. While Elsa's body faces away from the reader and seems ready to confront Anna, her reflected gaze points vaguely to the right of the image, her mouth slightly open in uncertainty. This doubling might also be seen to echo Anna's larger character-arc, in which she longs to be the heroic masculine figure capable of saving the realm from Elsa's sorcery, but also wants to be the beautiful ingenue, "Fetchingly draped against the wall / The picture of sophisticated grace." Anna is no prince charming--but she sure can dress for the role.

One thing is certain. In aligning the viewer with Anna, Frozen both re-creates and revises one of Disney's most oft-repeated images. Whether this hybridity represents a feminist deconstruction of a powerful gender stereotype or a hypocritical "feminist" gesture in a story mired by inherited images and old forms is a philosophical question beyond the scope of this blog. That such a question might emerge from a single freeze-frame in a popular Disney film, however, is a testament to the power and complexity of images, even those images that flash momentarily on the screen in one of the year's many blockbuster entertainments.

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago