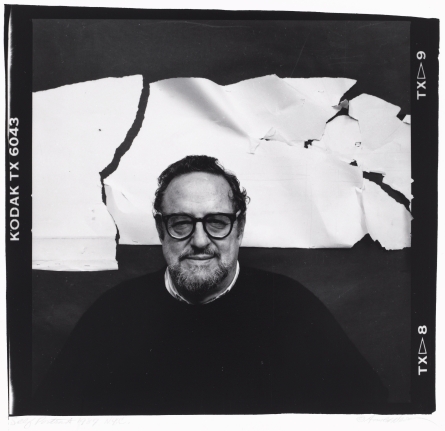

An Arnold Newman "selfie" from 1987. Image credit: The Jewish Museum

One of my favorite parts of the Harry Ransom Center’s current exhibition on Arnold Newman is the way it resists chronology. Newman’s photographs are organizes by particular attention to one of ten elements of Newman’s photography as artistic practice: “searches,” “choices,” “fronts,” “geometries,” “habitats,” “lumen,” “rhythms,” “sensibilities,” “signatures,” and “weavings.” What results is an exhibit that resists a notion of Arnold Newman’s transformation over time. Instead, the exhibit suggests, audiences might read Newman by his unique manipulation of photography’s formal elements throughout his entire career.

The resistance to chronology is apparent, too, in the weaving, wandering nature of the physical exhibit. Temporary half-walls throughout the exhibition space designate no beginning or end point for audiences. Instead, the exhibit inspires audiences to accept Newman’s particular artistic practice across ten themes as definitive criteria for photographic excellence, and therefore evidence for celebrating the photographer himself.

Such a construction has encouraged me to think about the relationship between celebrated photographer and celebrated subject. Are there ways that these two categories inform each other in the case of Arnold Newman? Can we trace, even amidst the Harry Ransom Center’s achronological curation, a chronological shift in fame from photographer to photographed? How does fame work as a mechanism for those who garner fame by representing it and perhaps cultivating it? Can those who represent fame create it as well?

To accomplish such a task, I’d like to begin by examining some of Newman’s early portrait subjects. I’ve limited myself to what the Ransom Center has included in their exhibition in the exploration below. Each portrait contains a “fame ratio” rating, which I’ve calculated by dividing the amount of google hits the portrait subject and the search term “Arnold Newman” receive by the amount of google hits the portrait subject alone receives. The closer the fame ratio gets to one, the more, we might infer, that the fame of the portrait subject from a 2013 perspective depends on their portrayal by Arnold Newman.

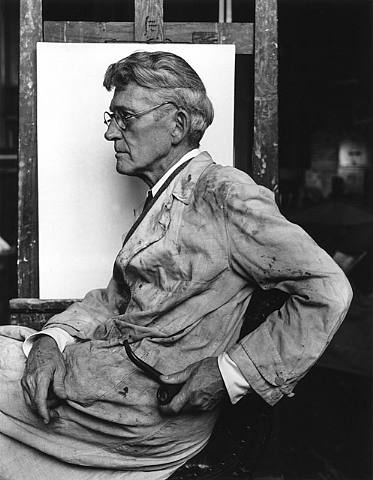

Image Credit: Chris Beetles

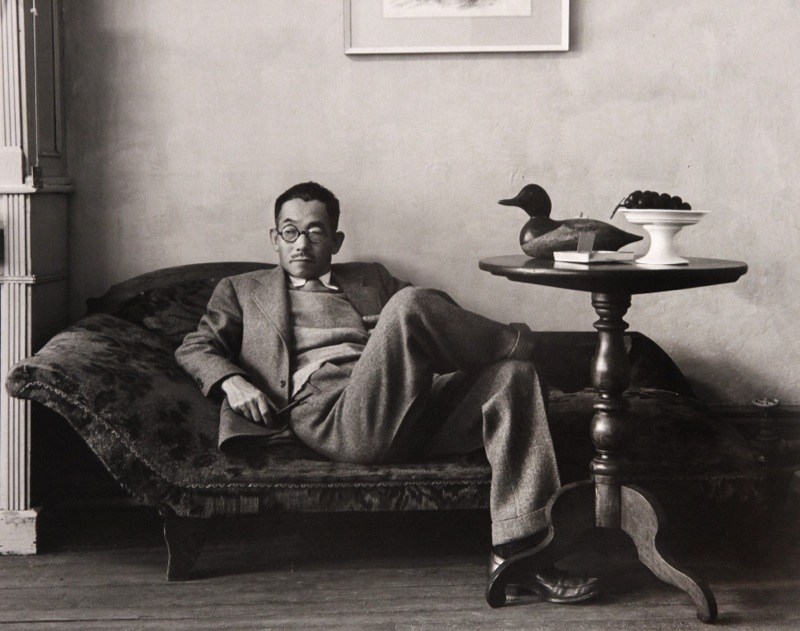

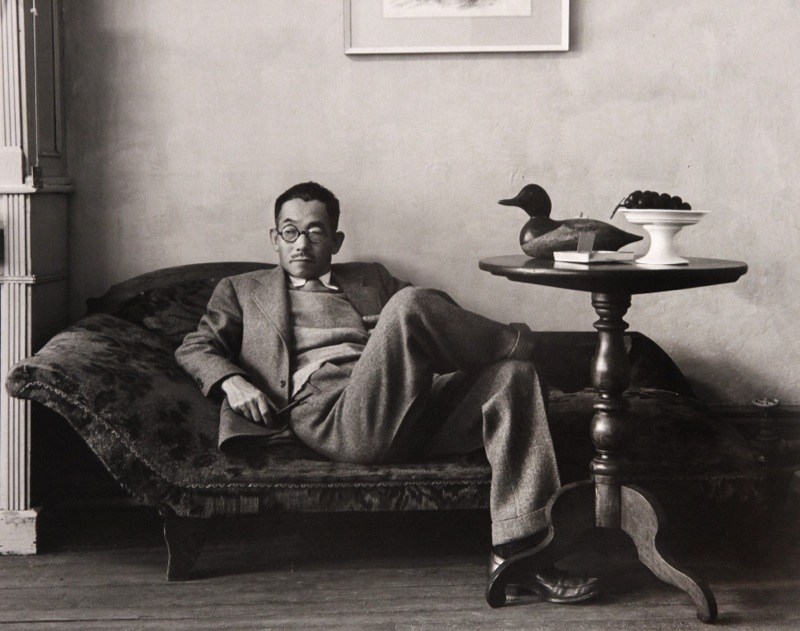

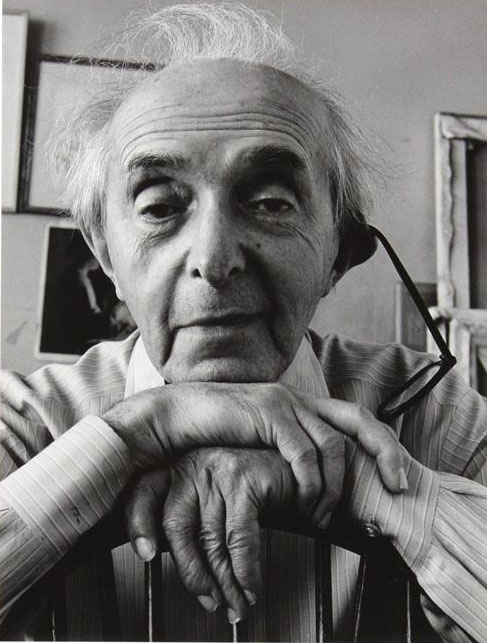

Yasuo Kuniyoshi, 1941 [Fame ratio: .46]

[Google search results in 55,300 results]

[of those results, 25,600 included reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

Without doing further archival research, I can say little about Kuniyoshi other than to assert he was an arguably minor figure in the New York art scene, especially in 1941, ten years after producing his most well-known works. Newman’s portrait of Kuniyoshi was probably mutually beneficial for Newman early in his career and Kuniyoshi late in his; now, evidence from Google suggests that Kuniyoshi is more reknowned for being Newman’s photographic subject than for his own innovating work in photography and lithography.

It is no coincidence that Newman was interested in Kuniyoshi; the two shared a similar interest in employing the naturalistic tradition in urban spaces.

Other portraits included from 1941:

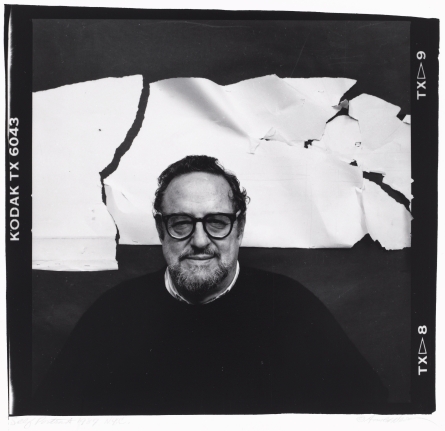

Image Credit: iCollector

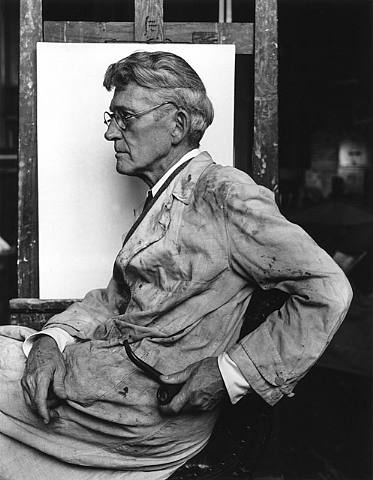

Raphael Soyer [Fame ratio: .22]

[Google search results in 77,500 results]

[of those results, 16,800 included reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

Image Credit: Phillip Koch Paintings

Image Credit: Phillip Koch Paintings

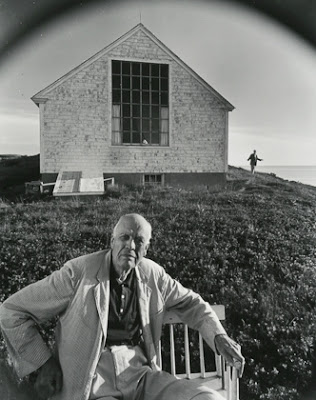

Edward Hopper [fame ratio: .03]

[Google search results in 1.76 million results]

[of those results, 49,200 included reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

Image Credit: Artnet

John French Sloan [Fame ratio: .02]

[Google search results in 300,000 results]

[of those results, 5,000 included reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

The trend of this data suggests that during 1941, Newman was able to establish a presence in the New York art community and transition from photographing minor figures to more major ones. However, the more famous the artist at the time Newman captured his photograph, the less their fame (present and future) depended upon their role as Newman’s photographic subject.

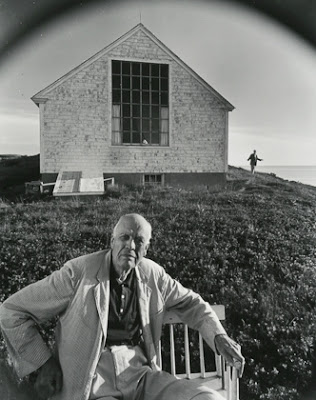

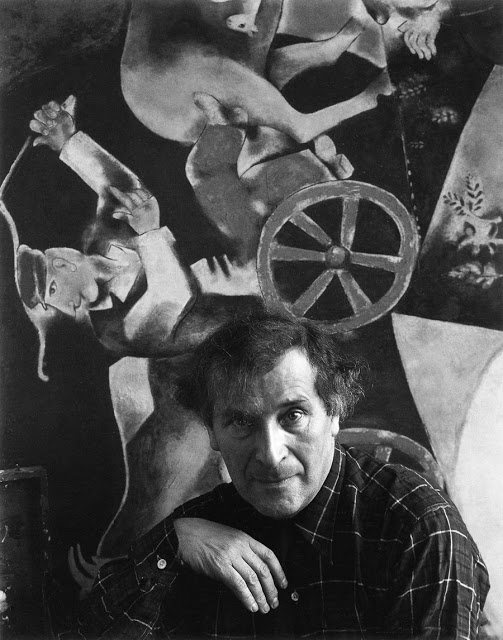

The exhibition also suggests that Newman’s 1941 photographs had a dramatic effect on the demand for his portraiture. Having achieved a reputation with his iconic 1941 photos, by 1942, Newman was no longer photographing minor figures. His subjects included arguably the most popular artists of the mid-century: Marc Chagall and Max Ernst.

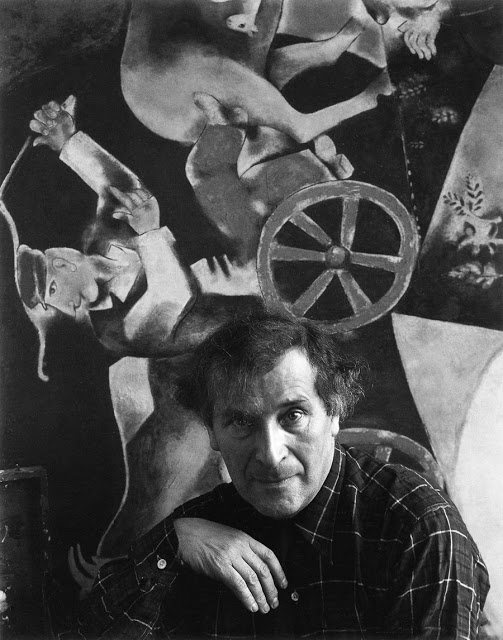

Image Credit: Anthony Luke Photography

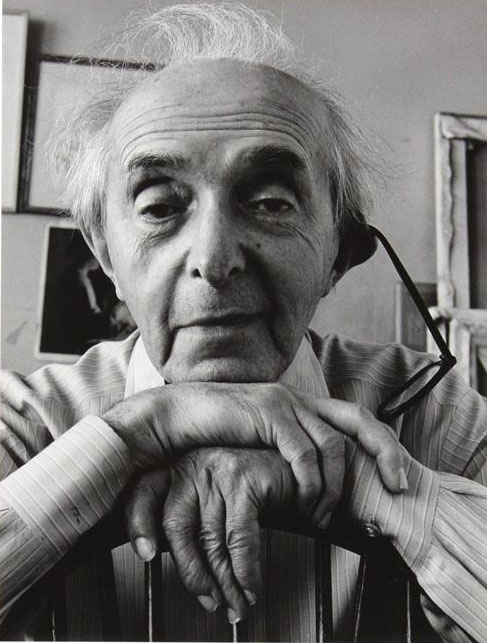

Marc Chagall, 1942 [Fame ratio: .01]

[Google search results in 4.2 million hits]

[of those hits, only 65,700 contained reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

Image Credit: Rice Cracker

Max Ernst, 1942 [Fame ratio: .004]

[Google search results in 2.34 million hits]

[of those hits, only 9,800 contained reference to Arnold Newman.]

--------------

By 1946, Newman was photographing the likes of Igor Stravinsky (perhaps Newman’s most iconic photograph) and Gore Vidal; figures of such fame seem to indicate that Newman’s portraiture had, by the mid 1940s, become an emblem or indication of celebrity, rather than a component in the creation of celebrity for the photographic subject.

This is not to say that Newman lost interest in photographing people who did not enjoy mass fame. Over the course of his career, Newman continued to photograph subjects whom he thought were influential or significant to modern life. Not all of those figures were vindicated by the test of time.

I would like to close, however, by suggesting that Newman’s own work enjoys an iconic status in its own right, even when the significance of the photographic subject has been forgotten. (We might, for instance, return to my first example of Yasuo Kuniyoshi.) Newman often insisted that his photographs must speak as both textually (that is, technically) and contextually competent objects. This is how we might define “iconic” in the case of Newman. The object must communicate meaning both in its composition and in its subtext. As Newman argues, "Successful portraiture is like a three-legged stool. Kick out one leg and the whole thing collapses. In other words, visual ideas combined with technological control combined with personal interpretation equals photography. Each must hold its own." In this way, a viewer might experience the lesser-known figures of the Newman exhibit as a sort of “death of the subject” akin to Foucault’s “death of the author.” In relieving the subject as the primary element of a photograph, we might, in the case of Newman’s archive, let the photographer speak.

The opinions expressed herein are solely those of viz. blog, and are not the product of the Harry Ransom Center.

Image Credit:

Image Credit:

Recent comments

2 years 29 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 44 weeks ago

2 years 50 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 4 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago

3 years 6 weeks ago